| You are here: | ||

| <<< Previous | Home | Next >>> |

This chapter describes the Architecture Development Method (ADM) cycle, adapting the ADM, architecture scope, and architecture integration.

The TOGAF ADM is the result of continuous contributions from a large number of architecture practitioners. It describes a method for developing an enterprise architecture, and forms the core of TOGAF. It integrates elements of TOGAF described in this document as well as other available architectural assets, to meet the business and IT needs of an organization.

The Enterprise Continuum provides a framework and context to support the leverage of relevant architecture assets in executing the ADM. These assets may include architecture descriptions, models, and patterns taken from a variety of sources, as explained in Part V: Enterprise Continuum & Tools.

The Enterprise Continuum is thus a tool for categorizing architectural source material - both the contents of the organization's own Architecture Repository, and the set of relevant, available reference models in the industry.

The practical implementation of the Enterprise Continuum will typically take the form of an Architecture Repository (see Part V, 41. Architecture Repository) that includes reference architectures, models, and patterns that have been accepted for use within the enterprise, and actual architectural work done previously within the enterprise. The architect would seek to re-use as much as possible from the Architecture Repository that was relevant to the project at hand. (In addition to the collection of architecture source material, the repository would also contain architecture development work-in-progress.)

At relevant places throughout the ADM, there are reminders to consider which, if any, architecture assets from the Architecture Repository the architect should use. In some cases - for example, in the development of a Technology Architecture - this may be the TOGAF Foundation Architecture (see Part VI: TOGAF Reference Models). In other cases - for example, in the development of a Business Architecture - it may be a reference model for e-Commerce taken from the industry at large.

The criteria for including source materials in an organization's Architecture Repository will typically form part of the enterprise architecture governance process. These governance processes should consider available resources both within and outside the enterprise in order to determine when general resources can be adapted for specific enterprise needs and also to determine where specific solutions can be generalized to support wider re-use.

In executing the ADM, the architect is not only developing a snapshot of the enterprise at particular points in time, but is also populating the organization's own Architecture Repository, with all the architectural assets identified and leveraged along the way, including, but not limited to, the resultant enterprise-specific architecture.

Architecture development is a continuous, cyclical process, and in executing the ADM repeatedly over time, the architect gradually adds more and more content to the organization's Architecture Repository. Although the primary focus of the ADM is on the development of the enterprise-specific architecture, in this wider context the ADM can also be viewed as the process of populating the enterprise's own Architecture Repository with relevant re-usable building blocks taken from the "left", more generic side of the Enterprise Continuum.

In fact, the first execution of the ADM will often be the hardest, since the architecture assets available for re-use will be relatively scarce. Even at this stage of development, however, there will be architecture assets available from external sources such as TOGAF, as well as the IT industry at large, that could be leveraged in support of the effort.

Subsequent executions will be easier, as more and more architecture assets become identified, are used to populate the organization's Architecture Repository, and are thus available for future re-use.

The ADM is also useful to populate the Foundation Architecture of an enterprise. Business requirements of an enterprise may be used to identify the necessary definitions and selections in the Foundation Architecture. This could be a set of re-usable common models, policy and governance definitions, or even as specific as overriding technology selections (e.g., if mandated by law). Population of the Foundation Architecture follows similar principles as for an enterprise architecture, with the difference that requirements for a whole enterprise are restricted to the overall concerns and thus less complete than for a specific enterprise.

It is important to recognize that existing models from these various sources, when integrated, may not necessarily result in a coherent enterprise architecture. "Integratability" of architecture descriptions is considered in 5.6 Architecture Integration .

Part III: ADM Guidelines and Techniques is is a set of resources - guidelines, templates, checklists, and other detailed materials - that support application of the TOGAF ADM.

The individual guidelines and techniques are described separately in Part III: ADM Guidelines and Techniques so that they can be referenced from the relevant points in the ADM as necessary, rather than having the detailed text clutter the description of the ADM itself.

The following are the key points about the ADM:

These issues are considered in detail in 5.3 Adapting the ADM .

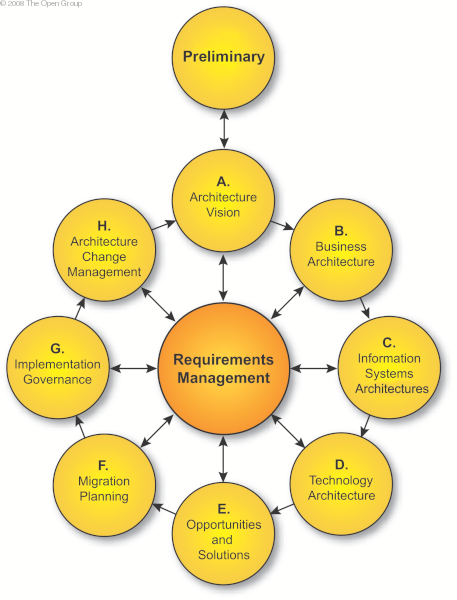

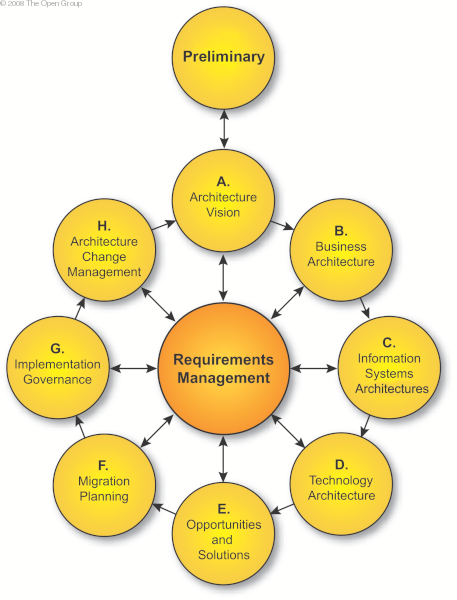

The basic structure of the ADM is shown in Architecture Development Cycle .

Throughout the ADM cycle, there needs to be frequent validation of results against the original expectations, both those for the whole ADM cycle, and those for the particular phase of the process.

The phases of the ADM cycle are further divided into steps; for example, the steps within the Technology Architecture phase are as follows:

The phases of the cycle are described in detail in the following chapters within Part II.

Note that output is generated throughout the process, and that the output in an early phase may be modified in a later phase. The versioning of output is managed through version numbers. In all cases, the ADM numbering scheme is provided as an example. It should be adapted by the architect to meet the requirements of the organization and to work with the architecture tools and repositories employed by the organization.

In particular, a version numbering convention is used within the ADM to illustrate the evolution of Baseline and Target Architecture Definitions. ADM Version Numbering Convention describes how this convention is used.

|

Phase |

Deliverable |

Content |

Version |

Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A: Architecture Vision |

Architecture |

Business |

0.1 |

Version 0.1 indicates that a high-level outline of the architecture is in place. |

|

|

|

Data |

0.1 |

Version 0.1 indicates that a high-level outline of the architecture is in place. |

|

|

|

Application |

0.1 |

Version 0.1 indicates that a high-level outline of the architecture is in place. |

|

|

|

Technology |

0.1 |

Version 0.1 indicates that a high-level outline of the architecture is in place. |

|

B: Business Architecture |

Architecture |

Business |

1.0 |

Version 1.0 indicates a formally reviewed, detailed architecture. |

|

C: Information Systems |

Architecture |

Data |

1.0 |

Version 1.0 indicates a formally reviewed, detailed architecture. |

|

|

|

Application |

1.0 |

Version 1.0 indicates a formally reviewed, detailed architecture. |

|

D: Technology Architecture |

Architecture |

Technology |

1.0 |

Version 1.0 indicates a formally reviewed, detailed architecture. |

The ADM is a generic method for architecture development, which is designed to deal with most system and organizational requirements. However, it will often be necessary to modify or extend the ADM to suit specific needs. One of the tasks before applying the ADM is to review its components for applicability, and then tailor them as appropriate to the circumstances of the individual enterprise. This activity may well produce an "enterprise-specific" ADM.

One reason for wanting to adapt the ADM, which it is important to stress, is that the order of the phases in the ADM is to some extent dependent on the maturity of the architecture discipline within the enterprise. For example, if the business case for doing architecture at all is not well recognized, then creating an Architecture Vision is almost always essential; and a detailed Business Architecture often needs to come next, in order to underpin the Architecture Vision, detail the business case for remaining architecture work, and secure the active participation of key stakeholders in that work. In other cases a slightly different order may be preferred; for example, a detailed inventory of the baseline environment may be done before undertaking the Business Architecture.

The order of phases may also be defined by the business and architecture principles of an enterprise. For example, the business principles may dictate that the enterprise be prepared to adjust its business processes to meet the needs of a packaged solution, so that it can be implemented quickly to enable fast response to market changes. In such a case, the Business Architecture (or at least the completion of it) may well follow completion of the Information Systems Architecture or the Technology Architecture.

Another reason for wanting to adapt the ADM is if TOGAF is to be integrated with another enterprise framework (as explained in Part I, 2.10 Using TOGAF with Other Frameworks). For example, an enterprise may wish to use TOGAF and its generic ADM in conjunction with the well-known Zachman Framework,1 or another enterprise architecture framework that has a defined set of deliverables specific to a particular vertical sector: Government, Defense, e-Business, Telecommunications, etc. The ADM has been specifically designed with this potential integration in mind.

Other possible reasons for wanting to adapt the ADM include:

The ADM, whether adapted by the organization or used as documented here, is a key process to be managed in the same manner as other architecture artifacts classified through the Enterprise Continuum and held in the Architecture Repository. The Architecture Board should be satisfied that the method is being applied correctly across all phases of an architecture development iteration. Compliance with the ADM is fundamental to the governance of the architecture, to ensure that all considerations are made and all required deliverables are produced.

The management of all architectural artifacts, governance, and related processes should be supported by a controlled environment. Typically this would be based on one or more repositories supporting versioned object and process control and status.

The major information areas managed by a governance repository should contain the following types of information:

The governance artifacts and process are themselves part of the contents of the Architecture Repository.

There are many reasons to constrain (or restrict) the scope of the architectural activity to be undertaken, most of which relate to limits in:

The scope chosen for the architecture activity should ideally allow the work of all architects within the enterprise to be effectively governed and integrated. This requires a set of aligned "architecture partitions" that ensure architects are not working on duplicate or conflicting activities. It also requires the definition of re-use and compliance relationships between architecture partitions.

The division of the enterprise and its architecture-related activity is discussed in more detail in 40. Architecture Partitioning .

Four dimensions are typically used in order to define and limit the scope of an architecture:

Typically, the scope of an architecture is first expressed in terms of enterprise scope, time period, and level of detail. Once the organizational scope is understood, a suitable combination of architecture domains can be selected that are appropriate to the problem being addressed.

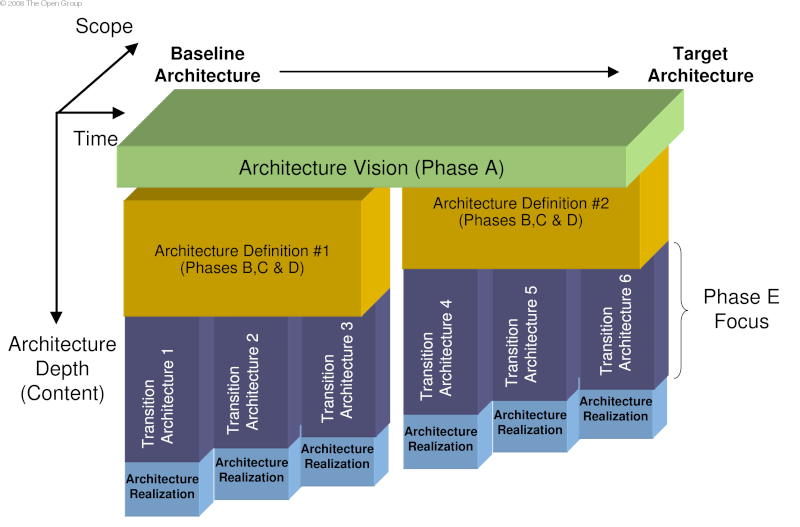

Progressive Architecture Development shows how architecture deliverables from different phases of the ADM may actually occupy different scope areas, with each phase progressively adding more specific detail.

This approach can be particularly effective when a long-term vision is needed, but the initial stages of implementation will only deliver a fraction of that vision. In these circumstances the more detailed architectures can initially be produced to address a much shorter time period, with additional architectures developed "just in time" for the next phase of implementation.

An alternative and complementary approach to segmenting the architecture in this respect is to use a full cycle of the ADM to address a particular area of scope. Subsequent ADM cycles can then be used to create more detailed architectures, as needed.

Techniques for using the ADM to develop a number of related architectures are discussed in 20.4 ADM Cycle Approaches .

The four dimensions of architecture scope are explored in detail below. In each case, particularly in largescale environments where architectures are necessarily developed in a federated manner, there is a danger of architects optimizing within their own scope of activity, instead of at the level of the overall enterprise. It is often necessary to sub-optimize in a particular area, in order to optimize at the enterprise level. The aim should always be to seek the highest level of commonality and focus on scalable and re-usable modules in order to maximize re-use at the enterprise level.

One of the key decisions is the focus of the architecture effort, in terms of the breadth of overall enterprise activity to be covered (which specific business sectors, functions, organizations, geographical areas, etc.).

One important factor in this context is the increasing tendency for largescale architecture developments to be undertaken in the form of "federated architectures" - independently developed, maintained, and managed architectures that are subsequently integrated within a meta-architecture framework. Such a framework specifies the principles for interoperability, migration, and conformance. This allows specific business units to have architectures developed and governed as stand-alone architecture projects. More details and guidance on specifying the interoperability requirements for different solutions can be found in 29. Interoperability Requirements .

Complex architectures are extremely hard to manage, not only in terms of the architecture development process itself, but also in terms of getting buy-in from large numbers of stakeholders. This in turn requires a very disciplined approach to identifying common architectural components, and management of the commonalities between federated components - deciding how to integrate, what to integrate, etc.

There are two basic approaches to federated architecture development:

The vertical segmentation approach discussed above is supported in TOGAF by the use of "partitioning" architectures into areas of discrete scope coverage. The approach to partitioning is discussed in Part V, 40. Architecture Partitioning .

Current experience does seem to indicate that, in order to cope with the increasingly broad focus and ubiquity of architectures, it is often necessary to have a number of different architectures existing across an enterprise, focused on particular timeframes, business functions, or business requirements; and this phenomenon would seem to call into question the feasibility of a single enterprise-wide architecture for every business function or purpose. In such cases, the paramount need is to manage and exploit the "federations" of architecture. A good starting point is to adopt a publish-and-subscribe model that allows architecture to be brought under a governance framework. In such a model, architecture developers and architecture consumers in projects (the supply and demand sides of architecture work) sign up to a mutually beneficial framework of governance that ensures that:

Publish and subscribe techniques are being developed as part of general IT governance and specifically for the Defense sphere.

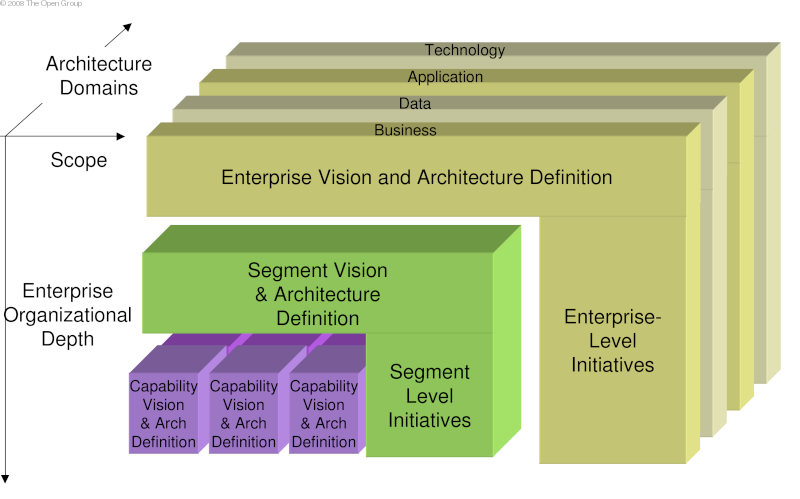

A complete enterprise architecture should address all four architecture domains (business, data, application, technology), but the realities of resource and time constraints often mean there is not enough time, funding, or resources to build a top-down, all-inclusive architecture description encompassing all four architecture domains.

Architecture descriptions will normally be built with a specific purpose in mind - a specific set of business drivers that drive the architecture development - and clarifying the specific issue(s) that the architecture description is intended to help explore, and the questions it is expected to help answer, is an important part of the initial phase of the ADM.

For example, if the purpose of a particular architecture effort is to define and examine technology options for achieving a particular capability, and the fundamental business processes are not open to modification, then a full Business Architecture may well not be warranted. However, because the Data, Application, and Technology Architectures build on the Business Architecture, the Business Architecture still needs to be thought through and understood.

While circumstances may sometimes dictate building an architecture description not containing all four architecture domains, it should be understood that such an architecture cannot, by definition, be a complete enterprise architecture. One of the risks is lack of consistency and therefore ability to integrate. Integration either needs to come later - with its own costs and risks - or the risks and trade-offs involved in not developing a complete and integrated architecture need to be articulated by the architect, and communicated to and understood by the enterprise management.

Care should be taken to judge the appropriate level of detail to be captured, based on the intended use of the enterprise architecture and the decisions to be made based on it. It is important that a consistent and equal level of depth be completed in each architecture domain (business, data, application, technology) included in the architecture effort. If pertinent detail is omitted, the architecture may not be useful. If unnecessary detail is included, the architecture effort may exceed the time and resources available, and/or the resultant architecture may be confusing or cluttered. Developing architectures at different levels of detail within an enterprise is discussed in more detail in 20. Applying the ADM at Different Enterprise Levels .

It is also important to predict the future uses of the architecture so that, within resource limitations, the architecture can be structured to accommodate future tailoring, extension, or re-use. The depth and detail of the enterprise architecture needs to be sufficient for its purpose, and no more.

However, it is not necessary to aim to complete a detailed architecture description at the first attempt. Future iterations of the ADM, in a further architecture development cycle, will build on the artifacts and the competencies created during the current iteration.

The bottom line is that there is a need to document all the models in an enterprise, to whatever level of detail is affordable, within an assessment of the likelihood of change and the concomitant risk, and bearing in mind the need to integrate the components of the different architecture domains (business, data, application, technology). The key is to understand the status of the enterprise's architecture work, and what can realistically be achieved with the resources and competencies available, and then focus on identifying and delivering the value that is achievable. Stakeholder value is a key focus: too broad a scope may deter some stakeholders (no return on investment).

The ADM is described in terms of a single cycle of Architecture Vision, and a set of Target Architectures (Business, Data, Application, Technology) that enable the implementation of the vision.

However, when the enterprise scope is large, and/or the Target Architectures particularly complex, the development of Target Architecture Descriptions may encounter major difficulties, or indeed prove "mission impossible", especially if being undertaken for the first time.

In such cases, a wider view may be taken, whereby an enterprise is represented by several different architecture instances (for example, strategic, segment, capability), each representing the enterprise at a particular point in time. One architecture instance will represent the current enterprise state (the "as-is", or baseline). Another architecture instance, perhaps defined only partially, will represent the ultimate target end-state (the "vision"). In-between, intermediate or "Transition Architecture" instances may be defined, each comprising its own set of Target Architecture Descriptions. An example of how this might be achieved is given in Part III, 20. Applying the ADM at Different Enterprise Levels .

By this approach, the Target Architecture work is split into two or more discrete stages:

In such an approach, the Target Architectures are evolutionary in nature, and require periodic review and update according to evolving business requirements and developments in technology, whereas the Transition Architectures are (by design) incremental in nature, and in principle should not evolve during the implementation phase of the increment, in order to avoid the "moving target" syndrome. This, of course, is only possible if the implementation schedule is under tight control and relatively short (typically less than two years).

The Target Architectures remain relatively generic, and because of that are less vulnerable to obsolescence than the Transition Architectures. They embody only the key strategic architectural decisions, which should be blessed by the stakeholders from the outset, whereas the detailed architectural decisions in the Transition Architectures are deliberately postponed as far as possible (i.e., just before implementation) in order to improve responsiveness vis a vis new technologies and products.

The enterprise evolves by migrating to each of these Transition Architectures in turn. As each Transition Architecture is implemented, the enterprise achieves a consistent, operational state on the way to the ultimate vision. However, this vision itself is periodically updated to reflect changes in the business and technology environment, and in effect may never actually be achieved, as originally described. The whole process continues for as long as the enterprise exists and continues to change.

Such a breakdown of the architecture description into a family of related architecture products of course requires effective management of the set and their relationships.

There is a need to provide an integration framework that sits above the individual architectures. This can be an "enterprise framework" such as the Content Framework (see Part IV, 33. Introduction) to position the various domains and artifacts, or it may be a meta-architecture framework (i.e., principles, models, and standards) to allow interoperability, migration, and conformance between federated architectures. The purpose of this meta-architecture framework is to:

There are varying degrees of architecture description "integratability". At the low end, integratability means that different architecture descriptions (whether prepared by one organizational unit or many) should have a "look-and-feel" that is sufficiently similar to enable critical relationships between the descriptions to be identified, thereby at least indicating the need for further investigation. At the high end, integratability ideally means that different descriptions should be capable of being combined into a single logical and physical representation.

Architectures that are created to address a subset of issues within an enterprise require a consistent frame of reference so that they can be considered as a group as well as point deliverables. The dimensions that are used to define the scope boundary of a single architecture (e.g., level of detail, architecture domain, etc.) are typically the same dimensions that must be addressed when considering the integration of many architectures. Integration of Architecture Artifacts illustrates how different types of architecture need to co-exist.

At the present time, the state of the art is such that architecture integration can be accomplished only at the lower end of the integratability spectrum. Key factors to consider are the granularity and level of detail in each artifact, and the maturity of standards for the interchange of architectural descriptions.

As organizations address common themes (such as Service Oriented Architecture (SOA), and integrated information infrastructure), and universal data models and standard data structures emerge, integration toward the high end of the spectrum will be facilitated. However, there will always be the need for effective standards governance to reduce the need for manual co-ordination and conflict resolution.

The TOGAF ADM defines a recommended sequence for the various phases and steps involved in developing an architecture, but it cannot recommend a scope - this has to be determined by the organization itself, bearing in mind that the recommended sequence of development in the ADM process is an iterative one, with the depth and breadth of scope and deliverables increasing with each iteration. Each iteration will add resources to the organization's Architecture Repository.

The choice of scope is critical to the success of the architecting effort. The key factor here is the sheer complexity of a complete, horizontally and vertically integrated enterprise architecture, as represented by a fully populated instantiation of the Zachman Framework. Very few enterprise architecture developments today actually undertake such an effort in a single development project, simply because it is widely recognized to be at the limits of the state of the art, a fact that John Zachman himself recognizes:

"Some day, you are going to wish you had all these models ... However, I am not so altruistic to think that we have to have them all today ... or even that we understand how to build and manage them all today. But the very fact that we can identify conceptually where we want to get some day, makes us think more about what we are doing in the current timeframe that might prevent us from getting to where we want to go in the future." (Quote from email correspondence from John Zachman to George Brundage.)

John Zachman himself likes to point out the alternatives available to those who can't countenance the amount of work implied in developing all the models required in his framework. There are only three choices:

all of which are risky and/or hugely expensive. What is necessary due to the pace of change is to have a set of readily deployable artifacts and a process for assembling them swiftly.

While such a complete framework is useful (indeed, essential) to have in mind as the ultimate long-term goal, in practice there is a key decision to be made as to the scope of a specific enterprise architecture effort. This being the case, it is vital to understand the basis on which scoping decisions are being made, and to set expectations right for what is the goal of the effort.

The main guideline is to focus on what creates value to the enterprise, and to select horizontal and vertical scope, and time periods, accordingly. Whether or not this is the first time around, understand that this exercise will be repeated, and that future iterations will build on what is being created in the current effort, adding greater width and depth.

The TOGAF document set is designed for use with frames. To navigate around the document:

Downloads of the TOGAF documentation, are available under license from the TOGAF information web site. The license is free to any organization wishing to use TOGAF entirely for internal purposes (for example, to develop an information system architecture for use within that organization). A book is also available (in hardcopy and pdf) from The Open Group Bookstore as document G091.