| You are here: | ||

| <<< Previous | Home | Next >>> |

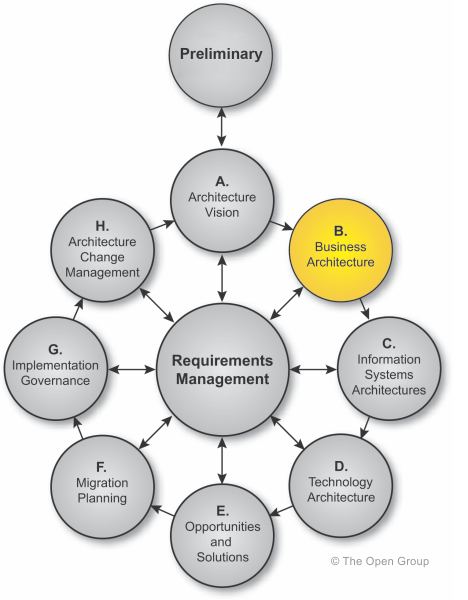

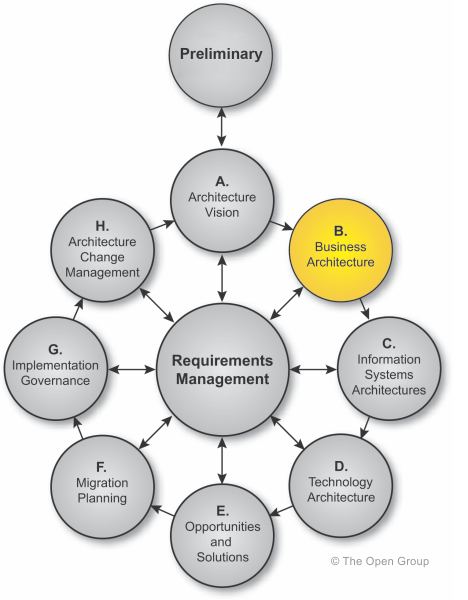

This chapter describes the development of a Business Architecture to support an agreed Architecture Vision.

The objectives of Phase B are to:

In summary, the Business Architecture describes the product and/or service strategy, and the organizational, functional, process, information, and geographic aspects of the business environment.

A knowledge of the Business Architecture is a prerequisite for architecture work in any other domain (Data, Application, Technology), and is therefore the first architecture activity that needs to be undertaken, if not catered for already in other organizational processes (enterprise planning, strategic business planning, business process re-engineering, etc.).

In practical terms, the Business Architecture is also often necessary as a means of demonstrating the business value of subsequent architecture work to key stakeholders, and the return on investment to those stakeholders from supporting and participating in the subsequent work.

The scope of the work in Phase B will depend to a large extent on the enterprise environment. In some cases, key elements of the Business Architecture may be done in other activities; for example, the enterprise mission, vision, strategy, and goals may be documented as part of some wider business strategy or enterprise planning activity that has its own lifecycle within the enterprise.

In such cases, there may be a need to verify and update the currently documented business strategy and plans, and/or to bridge between high-level business drivers, business strategy, and goals on the one hand, and the specific business requirements that are relevant to this architecture development effort. The business strategy typically defines what to achieve - the goals and drivers, and the metrics for success - but not how to get there. That is role of the Business Architecture.

In other cases, little or no Business Architecture work may have been done to date. In such cases, there will be a need for the architecture team to research, verify, and gain buy-in to the key business objectives and processes that the architecture is to support. This may be done as a free-standing exercise, either preceding architecture development, or as part of Phase A.

In both of these cases, the business scenario technique (see Part III, 26. Business Scenarios and Business Goals) of the TOGAF ADM, or any other method that illuminates the key business requirements and indicates the implied technical requirements for IT architecture, may be used.

A key objective is to re-use existing material as much as possible. In architecturally more mature environments, there will be existing Architecture Definitions, which (hopefully) will have been maintained since the last architecture development cycle. Where architecture descriptions exist, these can be used as a starting point, and verified and updated if necessary; see Part V, 39.4.1 Architecture Continuum.

Gather and analyze only that information that allows informed decisions to be made relevant to the scope of this architecture effort. If this effort is focused on the definition of (possibly new) business processes, then Phase B will necessarily involve a lot of detailed work. If the focus is more on the Target Architectures in other domains (data/information, application systems, infrastructure) to support an essentially existing Business Architecture, then it is important to build a complete picture in Phase B without going into unnecessary detail.

If an enterprise has existing architecture descriptions, they should be used as the basis for the Baseline Description. This input may have been used already in Phase A in developing an Architecture Vision, and may even be sufficient in itself for the Baseline Description.

Where no such descriptions exist, information will have to be gathered in whatever format comes to hand.

The normal approach to Target Architecture development is top-down. In the Baseline Description, however, the analysis of the current state often has to be done bottom-up, particularly where little or no architecture assets exist. In such a case, the architect simply has to document the working assumptions about high-level architectures, and the process is one of gathering evidence to turn the working assumptions into fact, until the law of diminishing returns sets in.

Business processes that are not to be carried forward have no intrinsic value. However, when developing Baseline Descriptions in other architecture domains, architectural components (principles, models, standards, and current inventory) that are not to be carried forward may still have an intrinsic value, and an inventory may be needed in order to understand the residual value (if any) of those components.

Whatever the approach, the goal should be to re-use existing material as much as possible, and to gather and analyze only that information that allows informed decisions to be made regarding the Target Business Architecture. It is important to build a complete picture without going into unnecessary detail.

Business models should be logical extensions of the business scenarios from the Architecture Vision, so that the architecture can be mapped from the high-level business requirements down to the more detailed ones.

A variety of modeling tools and techniques may be employed, if deemed appropriate (bearing in mind the above caution not to go into unnecessary detail). For example:

The Object Management Group (OMG) has developed the Business Process Modeling Notation (BPMN), a standard for business process modeling that includes a language with which to specify business processes, their tasks/steps, and the documents produced.

All three types of model above can be represented in the Unified Modeling Language (UML), and a variety of tools exist for generating such models.

Certain industry sectors have modeling techniques specific to the sector concerned. For example, the Defense sector uses the following models. These models have to be used carefully, especially if the location and conduct of business processes will be altered in the visionary Business Architecture.

Although originally developed for use in the Defense sector, these models are finding increasing use in other sectors of government, and may also be considered for use in non-government environments.

As part of Phase B, the architecture team will need to consider what relevant Business Architecture resources are available from the Architecture Repository (see Part V, 41. Architecture Repository), in particular:

This section defines the inputs to Phase B.

The level of detail addressed in Phase B will depend on the scope and goals of the overall architecture effort.

New business processes being introduced as part of this effort will need to be defined in detail during Phase B. Existing business processes to be carried over and supported in the target environment may already have been adequately defined in previous architectural work; but, if not, they too will need to be defined in Phase B.

The order of the steps in Phase B (see below) as well as the time at which they are formally started and completed should be adapted to the situation at hand, in accordance with the established architecture governance. In particular, determine whether in this situation it is appropriate to conduct Baseline or Target Architecture development first, as described in Part III, 19. Applying Iteration to the ADM.

All activities that have been initiated in these steps must be closed during the Finalize the Business Architecture step (see 8.4.8 Finalize the Business Architecture). The documentation generated from these steps must be formally published in the Create Architecture Definition Document step (see 8.4.9 Create Architecture Definition Document).

The steps in Phase B are as follows:

Select relevant Business Architecture resources (reference models, patterns, etc.) from the Architecture Repository, on the basis of the business drivers, and the stakeholders and concerns.

Select relevant Business Architecture viewpoints (e.g., operations, management, financial); i.e., those that will enable the architect to demonstrate how the stakeholder concerns are being addressed in the Business Architecture.

Identify appropriate tools and techniques to be used for capture, modeling, and analysis, in association with the selected viewpoints. Depending on the degree of sophistication warranted, these may comprise simple documents or spreadsheets, or more sophisticated modeling tools and techniques, such as activity models, business process models, use-case models, etc.

For each viewpoint, select the models needed to support the specific view required, using the selected tool or method.

Ensure that all stakeholder concerns are covered. If they are not, create new models to address concerns not covered, or augment existing models (see 8.2.3 Business Modeling). Business scenarios are a useful technique to discover and document business requirements, and may be used iteratively, at different levels of detail in the hierarchical decomposition of the Business Architecture. Business scenarios are described in Part III, 26. Business Scenarios and Business Goals.

Activity models, use-case models, and class models are mentioned earlier as techniques to enable the definition of an organization's business architecture. In many cases, all three approaches can be utilized in sequence to progressively decompose a business.

The level and rigor of decomposition needed varies from enterprise to enterprise, as well as within an enterprise, and the architect should consider the enterprise's goals, objectives, scope, and purpose of the enterprise architecture effort to determine the level of decomposition.

The TOGAF content framework differentiates between the functions of a business and the services of a business. Business services are specific functions that have explicit, defined boundaries that are explicitly governed. In order to allow the architect flexibility to define business services at a level of granularity that is appropriate for and manageable by the business, the functions are split as follows: micro-level functions will have explicit, defined boundaries, but may not be explicitly governed. Likewise, macro business functions may be explicitly governed, but may not have explicit, defined boundaries.

The Business Architecture phase therefore needs to identify which components of the architecture are functions and which are services. Services are distinguished from functions through the explicit definition of a service contract. When Baseline Architectures are being developed, it may be the case that explicit contracts do not exist and it would therefore be at the discretion of the architect to determine whether there is merit in developing such contracts before examining any Target Architectures.

A service contract covers the business/functional interface and also the technology/data interface. Business Architecture will define the service contract at the business/functional level, which will be expanded on in the Application and Technology Architecture phases.

The granularity of business services should be determined according to the business drivers, goals, objectives, and measures for this area of the business. Finer-grained services permit closer management and measurement (and can be combined to create coarser-grained services), but require greater effort to govern. Guidelines for identification of services and definition of their contracts can be found in Part III, 22. Using TOGAF to Define & Govern SOAs.

Catalogs capture inventories of the core assets of the business. Catalogs are hierarchical in nature and capture the decomposition of a building block and also decompositions across related building blocks (e.g., organization/actor).

Catalogs form the raw material for development of matrices and views and also act as a key resource for portfolio managing business and IT capability.

The following catalogs should be considered for development within a Business Architecture:

The structure of catalogs is based on the attributes of metamodel entities, as defined in Part IV, 34. Content Metamodel.

Matrices show the core relationships between related model entities.

Matrices form the raw material for development of views and also act as a key resource for impact assessment, carried out as a part of gap analysis.

The following matrices should be considered for development within a Business Architecture:

The structure of matrices is based on the attributes of metamodel entities, as defined in Part IV, 34. Content Metamodel.

Diagrams present the Business Architecture information from a set of different perspectives (viewpoints) according to the requirements of the stakeholders.

The following Diagrams should be considered for development within a Business Architecture:

The structure of diagrams is based on the attributes of metamodel entities, as defined in Part IV, 34. Content Metamodel.

Once the Business Architecture catalogs, matrices, and diagrams have been developed, architecture modeling is completed by formalizing the business-focused requirements for implementing the Target Architecture.

These requirements may:

Within this step, the architect should identify requirements that should be met by the architecture (see 17.2.2 Requirements Development).

In many cases, the Architecture Definition will not be intended to give detailed or comprehensive requirements for a solution (as these can be better addressed through general requirements management discipline). The expected scope of requirements content should be established during the Architecture Vision phase and documented in the approved Statement of Architecture Work.

Any requirement or change in requirement that is outside of the scope defined in the Statement of Architecture Work must be submitted to the Requirements Repository for management through the governed Requirements Management process.

Develop a Baseline Description of the existing Business Architecture, to the extent necessary to support the Target Business Architecture. The scope and level of detail to be defined will depend on the extent to which existing business elements are likely to be carried over into the Target Business Architecture, and on whether architecture descriptions exist, as described in 8.2 Approach. To the extent possible, identify the relevant Business Architecture building blocks, drawing on the Architecture Repository (see Part V, 41. Architecture Repository).

Where new architecture models need to be developed to satisfy stakeholder concerns, use the models identified within Step 1 as a guideline for creating new architecture content to describe the Baseline Architecture.

Develop a Target Description for the Business Architecture, to the extent necessary to support the Architecture Vision. The scope and level of detail to be defined will depend on the relevance of the business elements to attaining the Target Architecture Vision, and on whether architectural descriptions exist. To the extent possible, identify the relevant Business Architecture building blocks, drawing on the Architecture Repository (see Part V, 41. Architecture Repository).

Where new architecture models need to be developed to satisfy stakeholder concerns, use the models identified within Step 1 as a guideline for creating new architecture content to describe the Target Architecture.

Verify the architecture models for internal consistency and accuracy:

Identify gaps between the baseline and target, using the Gap Analysis technique as described in Part III, 27. Gap Analysis.

Following creation of a Baseline Architecture, Target Architecture, and gap analysis results, a business roadmap is required to prioritize activities over the coming phases.

This initial Business Architecture roadmap will be used as raw material to support more detailed definition of a consolidated, cross-discipline roadmap within the Opportunities & Solutions phase.

Once the Business Architecture is finalized, it is necessary to understand any wider impacts or implications.

At this stage, other architecture artifacts in the Architecture Landscape should be examined to identify:

Check the original motivation for the architecture project and the Statement of Architecture Work against the proposed Business Architecture, asking if it is fit for the purpose of supporting subsequent work in the other architecture domains. Refine the proposed Business Architecture only if necessary.

If appropriate, use reports and/or graphics generated by modeling tools to demonstrate key views of the architecture. Route the document for review by relevant stakeholders, and incorporate feedback.

The outputs of Phase B may include, but are not restricted to:

The outputs may include some or all of the following:

The TOGAF document set is designed for use with frames. To navigate around the document:

Downloads of TOGAF®, an Open Group Standard, are available under license from the TOGAF information web site. The license is free to any organization wishing to use the TOGAF standard entirely for internal purposes (for example, to develop an information system architecture for use within that organization). A book is also available (in hardcopy and pdf) from The Open Group Bookstore as document G116.