| You are here: | ||

| <<< Previous | Home | Next >>> |

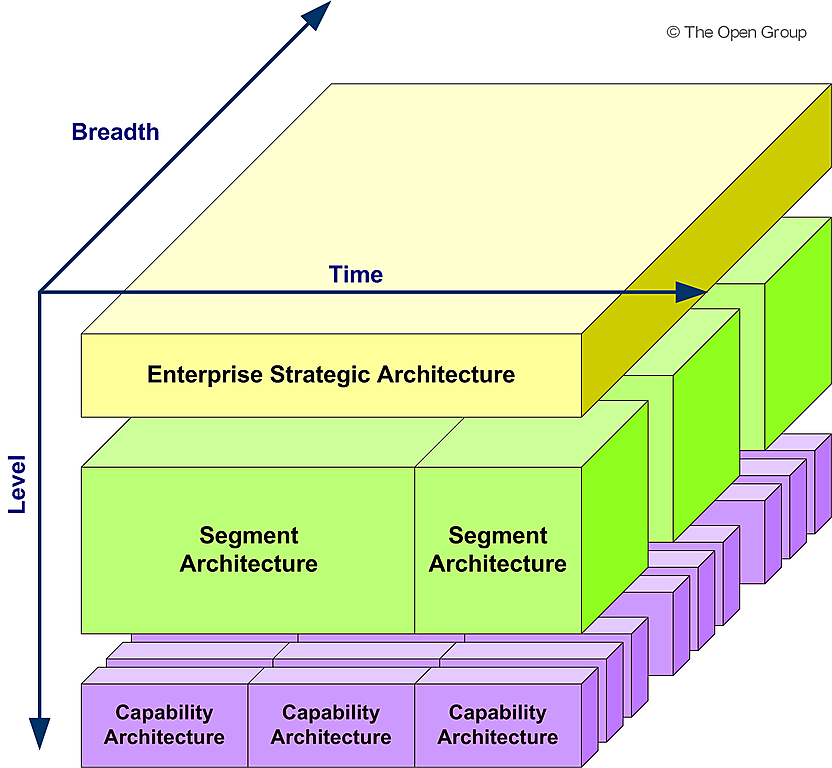

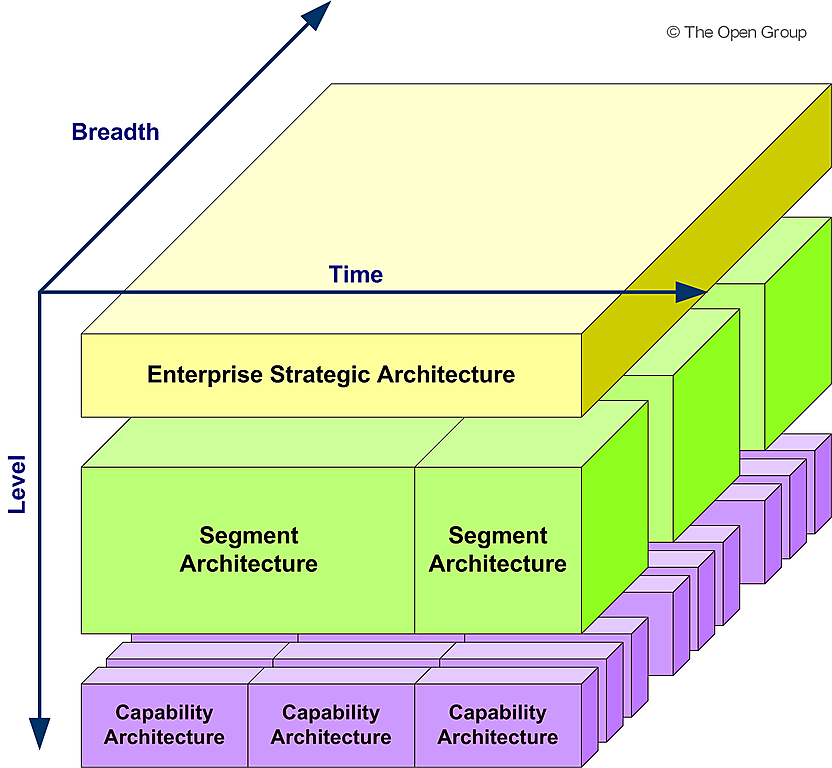

In a typical enterprise, many architectures will be described in the Architecture Landscape at any point in time. Some architectures will address very specific needs; others will be more general. Some will address detail; some will provide a big picture. To address this complexity, the TOGAF standard uses the concepts of levels and the Enterprise Continuum to provide a conceptual framework for organizing the Architecture Landscape. These concepts are tightly linked with organizing actual content in the Architecture Repository and any architecture partitions discussed in Part V.

Levels provide a framework for dividing the Architecture Landscape into three levels of granularity:

Figure 19-1 shows a summary of the classification model for Architecture Landscapes.

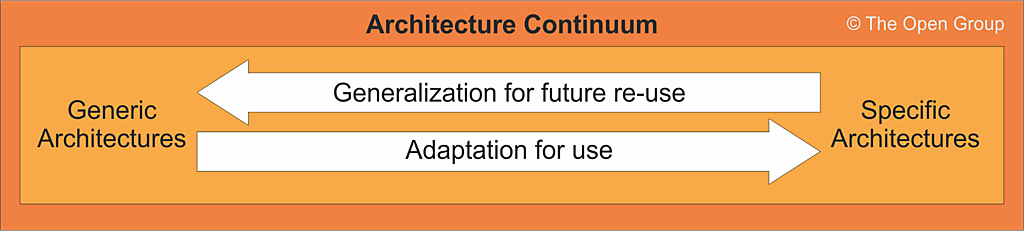

The Architecture Continuum provides a method of dividing each level of the Architecture Landscape (see 35.4.1 Architecture Continuum) by abstraction. It offers a consistent way to define and understand the generic rules, representations, and relationships in an architecture, including traceability and derivation relationships. The Architecture Continuum shows the relationships from foundation elements to organization-specific architecture, as shown in Figure 19-2 .

The Architecture Continuum is a useful tool to discover commonality and eliminate unnecessary redundancy.

Levels and the Architecture Continuum provide a comprehensive mechanism to describe and classify the Architecture Landscape. These concepts can be used to organize the Architecture Landscape into a set of related architectures with:

There is no definitive organizing model for architecture, as each enterprise should adopt a model that reflects its own operating model.

The following characteristics are typically used to organize the Architecture Landscape:

Architectures are functionally decomposed into a hierarchy of specific subject areas or segments.

More specific subject matter areas will generally permit (and require) more detailed architectures.

Broader and less detailed architectures will generally be valid for longer periods of time and can provide a vision for the enterprise that stretches further into the future.

After approval, an architecture will begin to decrease in accuracy if not actively maintained. In some cases recency may be used as an organizing factor for historic architectures.

Using the criteria above, architectures can be grouped into Strategic, Segment, and Capability Architecture levels, as described in Figure 19-1 .

The previous sections have identified that different types of architecture are required to address different stakeholder needs at different levels of the organization. Each architecture typically does not exist in isolation and must therefore sit within a governance hierarchy. Broad, summary architectures set the direction for narrow and detailed architectures.

A number of techniques can be employed to use the ADM as a process that supports such hierarchies of architectures. Essentially there are two strategies that can be applied:

At the extreme ends of the scale, either of these two options can be fully adopted. In practice, an architect is likely to need

to blend elements of each to fit the exact requirements of their Request for Architecture Work. Each of these approaches is

described in 18. Applying Iteration to the ADM .

return to top of page

return to top of page