Preface

The Open Group

The Open Group is a global consortium that enables the achievement of business objectives through technology standards. With more than 870 member organizations, we have a diverse membership that spans all sectors of the technology community – customers, systems and solutions suppliers, tool vendors, integrators and consultants, as well as academics and researchers.

The mission of The Open Group is to drive the creation of Boundaryless Information Flow™ achieved by:

- Working with customers to capture, understand, and address current and emerging requirements, establish policies, and share best practices

- Working with suppliers, consortia, and standards bodies to develop consensus and facilitate interoperability, to evolve and integrate specifications and open source technologies

- Offering a comprehensive set of services to enhance the operational efficiency of consortia

- Developing and operating the industry’s premier certification service and encouraging procurement of certified products

Further information on The Open Group is available at www.opengroup.org.

The Open Group publishes a wide range of technical documentation, most of which is focused on development of Standards and Guides, but which also includes white papers, technical studies, certification and testing documentation, and business titles. Full details and a catalog are available at www.opengroup.org/library

The TOGAF® Standard, a Standard of The Open Group

The TOGAF Standard is a proven enterprise methodology and framework used by the world’s leading organizations to improve business efficiency.

This Document

This document is a TOGAF® Series Guide to Business Models. It has been developed and approved by The Open Group.

More information is available, along with a number of tools, guides, and other resources, at www.opengroup.org/architecture.

About the TOGAF® Series Guides

The TOGAF® Series Guides contain guidance on how to use the TOGAF Standard and how to adapt it to fulfill specific needs.

The TOGAF® Series Guides are expected to be the most rapidly developing part of the TOGAF Standard and are positioned as the guidance part of the standard. While the TOGAF Fundamental Content is expected to be long-lived and stable, guidance on the use of the TOGAF Standard can be industry, architectural style, purpose, and problem-specific. For example, the stakeholders, concerns, views, and supporting models required to support the transformation of an extended enterprise may be significantly different than those used to support the transition of an in-house IT environment to the cloud; both will use the Architecture Development Method (ADM), start with an Architecture Vision, and develop a Target Architecture on the way to an Implementation and Migration Plan. The TOGAF Fundamental Content remains the essential scaffolding across industry, domain, and style.

Trademarks

ArchiMate, DirecNet, Making Standards Work, Open O logo, Open O and Check Certification logo, Platform 3.0, The Open Group, TOGAF, UNIX, UNIXWARE, and the Open Brand X logo are registered trademarks and Boundaryless Information Flow, Build with Integrity Buy with Confidence, Commercial Aviation Reference Architecture, Dependability Through Assuredness, Digital Practitioner Body of Knowledge, DPBoK, EMMM, FACE, the FACE logo, FHIM Profile Builder, the FHIM logo, FPB, Future Airborne Capability Environment, IT4IT, the IT4IT logo, O-AA, O-DEF, O-HERA, O-PAS, Open Agile Architecture, Open FAIR, Open Footprint, Open Process Automation, Open Subsurface Data Universe, Open Trusted Technology Provider, OSDU, Sensor Integration Simplified, SOSA, and the SOSA logo are trademarks of The Open Group.

A Guide to the Business Architecture Body of Knowledge, BIZBOK, and Business Architecture Guild are registered trademarks of the Business Architecture Guild.

Business Model Canvas is a trademark of Alexander Osterwalder.

All other brands, company, and product names are used for identification purposes only and may be trademarks that are the sole property of their respective owners.

Acknowledgements

The Open Group gratefully acknowledges the following people and organizations for their contribution to the development of this Guide:

(Please note affiliations were current at the time of approval.)

- The authors and reviewers – Steve DuPont, J. Bryan Lail, Stephen Marshall, Chalon Mullins, Alec Blair, and Mats Gejnevall

- Past and present members of The Open Group Architecture Forum

- The Business Architecture Guild for permission to reuse graphics

References to the Business Model Canvas are as per the usage conventions issued by strategyzer.com.

Referenced Documents

The following documents are referenced in this TOGAF® Series Guide:

- A Guide to the Business Architecture Body of Knowledge® (BIZBOK® Guide), Version 6.5, Business Architecture Guild®, 2018

- Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers, Alexander Osterwalder, Yves Pigneur, John Wiley & Sons, 2010

- Defining the IT Operating Model, White Paper (W17B), published by The Open Group, September 2017; refer to: www.opengroup.org/library/w17b

- Linking Business Models with Business Architecture to Drive Innovation, White Paper, Business Architecture Guild®, August 2015

- Seizing the White Space: Business Model Innovation for Growth and Renewal, Mark W. Johnson, Harvard Business Review Press, 2010

- The Age of the Platform: How Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google have Redefined Business, Phil Simon, Motion Publishing, 2011

- The Business Model Cube, Peter Lindgren, Ole Horn Rasmussen, Department of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering, Aalborg University, Denmark, 2013 (Journal of Multi Business Model Innovation and Technology, 135-182, River Publishers, 2013)

- The Business Model Innovation Factory: How to Stay Relevant when the World is Changing, Saul Kaplan, 2012

- The Five Competitive Forces that Shape Strategy, Michael E. Porter, Harvard Business Review Press, 2008

- The TOGAF® Standard, 10th Edition, a standard of The Open Group (C220), published by The Open Group, April 2022; refer to: www.opengroup.org/library/c220

- TOGAF® Series Guide: Business Capabilities, Version 2 (G211), published by The Open Group, April 2022; refer to: www.opengroup.org/library/g211

- TOGAF® Series Guide: Value Streams (G178), published by The Open Group, April 2022: refer to: www.opengroup.org/library/g178

- What is Business Design?, Rotman DesignWorks, Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto, 2015; refer to: www.rotman.utoronto.ca/FacultyAndResearch/EducationCentres/DesignWorks/About-BD

This TOGAF® Series Guide to Business Models provides a basis for Enterprise Architects to understand and utilize business models, which describe the rationale of how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value.[1] Business models provide a powerful construct to help focus and align an organization around its strategic vision and execution. In this Guide we cover different forms of business models and approaches to modeling, from the conceptual down to a practical example.

There is a direct relationship between the business innovation captured in these models and the approach to implementing that innovation through Enterprise Architecture. We explore that relation through Business Architecture methods such as value streams and business capabilities, then provide a specific example based on a generic retail company undertaking a Digital Transformation. An appendix delves deeper into the structure of one of the most commonly used business model frameworks for architects interested in working with business leaders to execute their strategy.

1.1 Overview

The world’s top C-suite leaders know that the effective management and exploitation of information is a key factor for business success, and is critical to developing and maintaining competitive advantage. An Enterprise Architecture supports this objective by providing a strategic context for the evolution of technologies in response to the constantly changing needs of the business environment.

As stated in the TOGAF Standard – Introduction and Core Concepts, a key goal of Enterprise Architecture is to create or enable the alignment of the business operations with the overall business direction (vision and strategy). Furthermore:

“… a good Enterprise Architecture enables you to achieve the right balance between business transformation and continuous operational efficiency. It allows individual business units to innovate safely in their pursuit of evolving business goals and competitive advantage. At the same time, the Enterprise Architecture enables the needs of the organization to be met with an integrated strategy which permits the closest possible synergies across the enterprise and beyond.”

To achieve this alignment, the architect must develop a fundamental understanding of the core elements that make up a business and how they relate to the ways in which it creates, captures, and delivers value. However, it is not always clear what the business direction is, or how the business intends to create, capture, and deliver value to customers and stakeholders. If we don’t fully understand what a business does or what it intends to do; why it exists; or how it works to produce something of value to stakeholders (while making money in the process), then how can architects devise an appropriate target-state environment that realizes the business objectives?

One effective way to achieve alignment between an organization’s strategic objectives and the target-state architecture is to employ the concept of the business model. Business model artifacts are used to:

- Provide a common understanding of what the organization is, or looks like, today

- Portray what it intends to become in the future

- Create a critical link between the business strategy and the required blueprints of the Enterprise Architecture that define what the business needs to transform to, along with the plans that describe how to do it

The rest of this Guide describes what business models are and how business model artifacts are constructed; their purpose and benefits; how to use modeling frameworks to create a business model artifact and perform business model innovation; and where to apply them within the realms of Enterprise Architecture and the TOGAF Architecture Development Method (ADM).

1.2 Objectives

The objectives of this Guide are to:

- Familiarize architects with the concept and purpose of business models

- Illustrate the concept and purpose by looking in some detail at one particular technique for creating and leveraging business model artifacts: the Business Model Canvas™

- Explain how business models relate to and influence the TOGAF ADM

The goal is for practitioners to be able to use business models to frame, scope, and define the boundaries of their architecture work, particularly in relation to creating current and target states for the Phase B: Business Architecture part of the ADM process. A key practice we apply to help achieve this goal is to follow Business Architecture principles from the best practices in the Business Architecture Guild®, such as the Guild White Paper that provided the basis for this Guide.[2]

A business model describes the rationale for how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value. This may refer only to an abstract concept that may exist in a leader’s mind. Or it may be more concrete, whereby business model artifacts provide specific views of an instance of a business model, defining the structural elements of the business model as well as the relationships between each element.

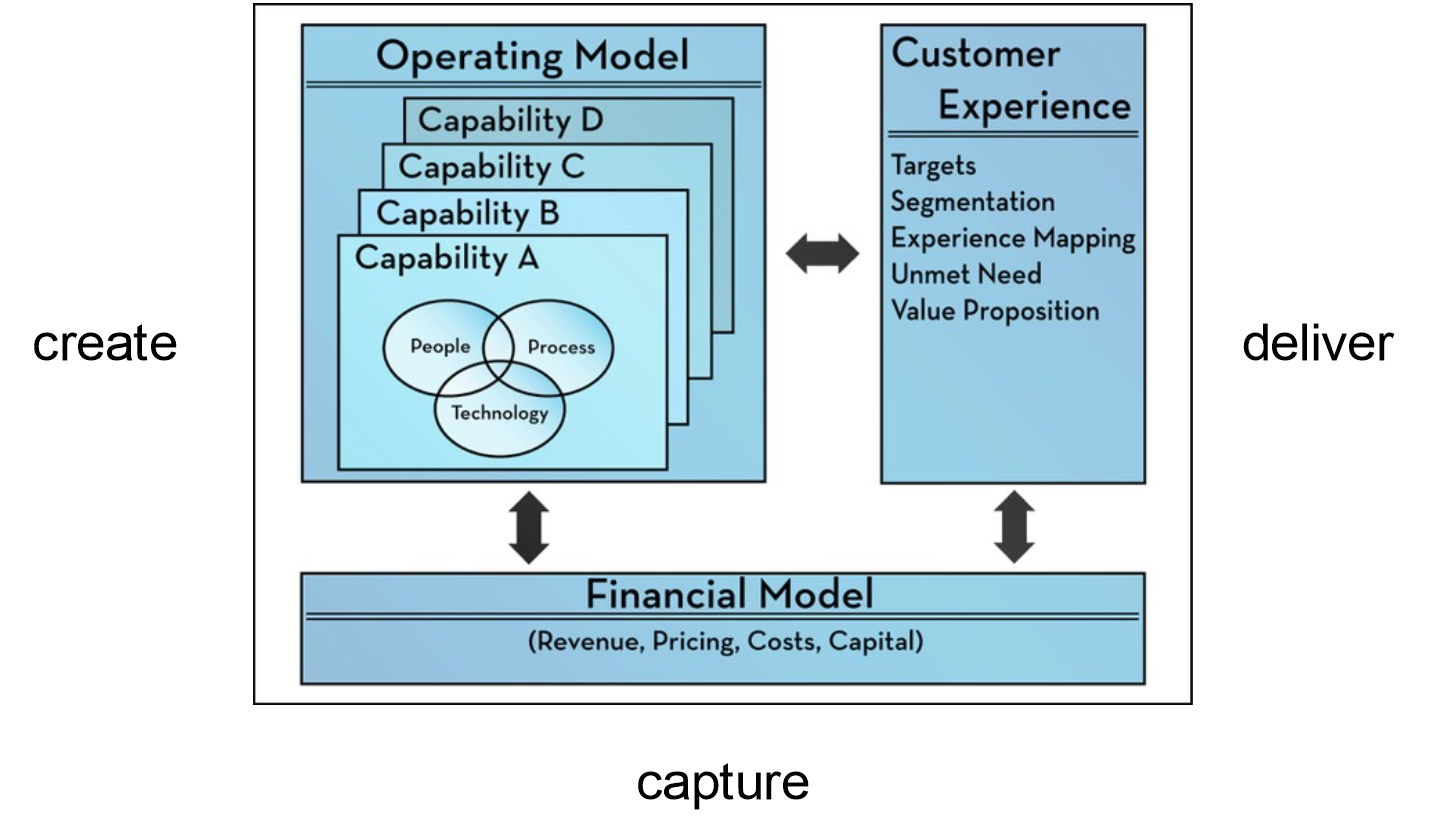

Business models can be represented in different ways. The three-element framework shown in Figure 1 describes the structure of a business model in its most abstract form.

(Source: The Business Model Innovation Factory, Saul Kaplan, 2012)

Figure 1: Abstract View of a Business Model

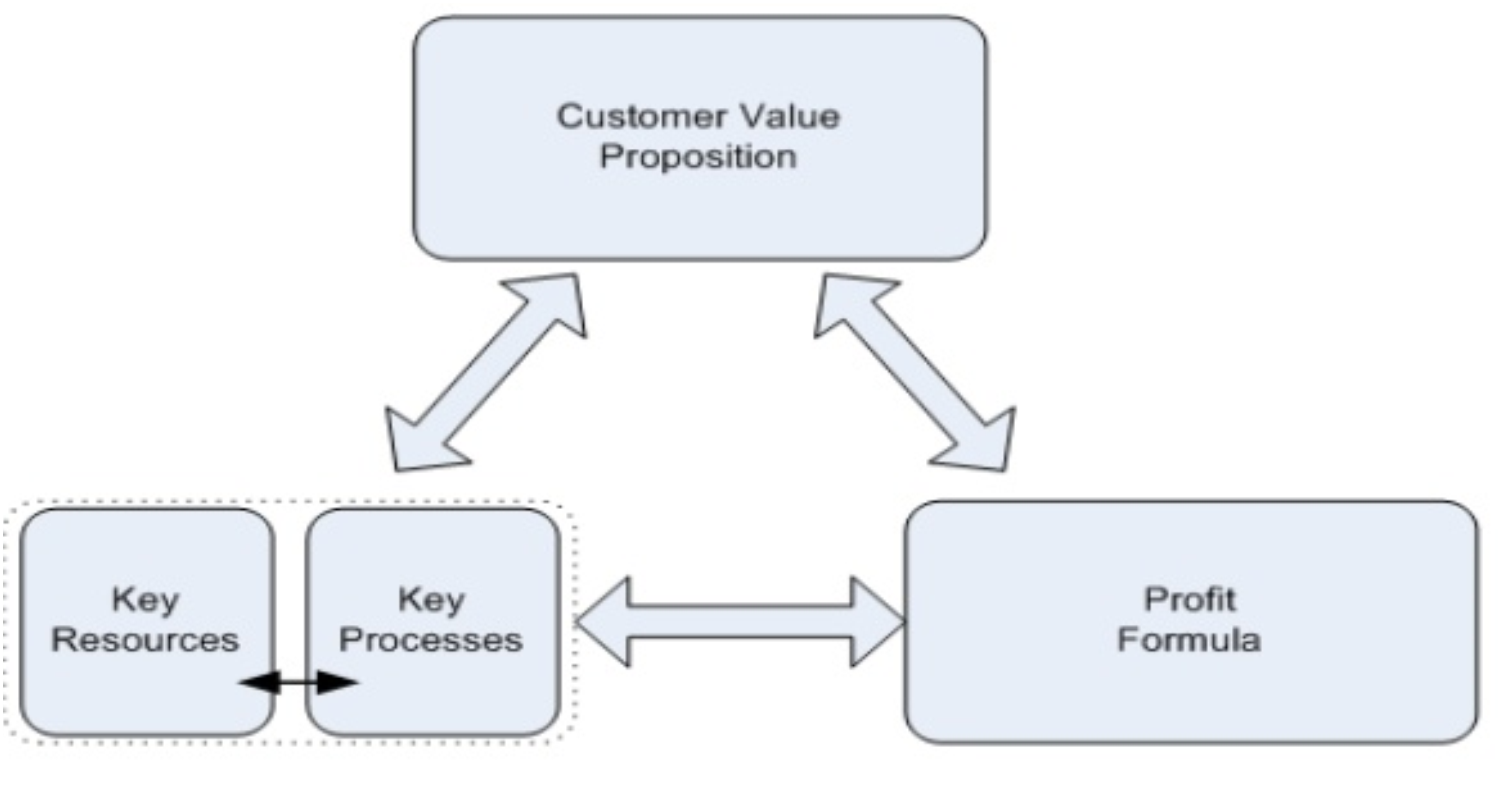

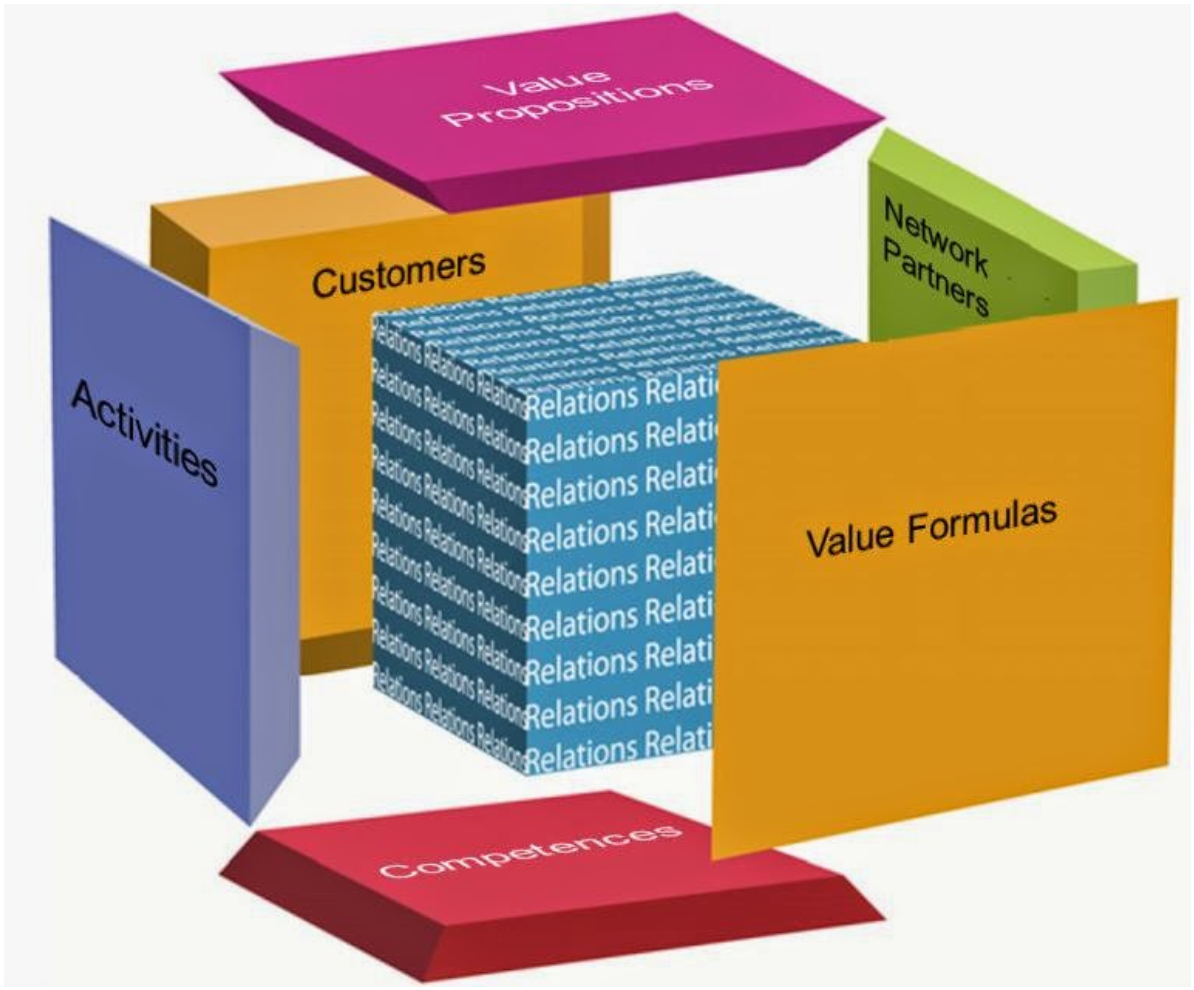

Other well-known framework examples include the Four-Box Framework (Figure 2) and the Business Model Cube (Figure 3).

(Source: Seizing the White Space, Mark W. Johnson, 2010)

(Source: The Business Model Cube, Peter Lindgren, Ole Horn Rasmussen, 2013)

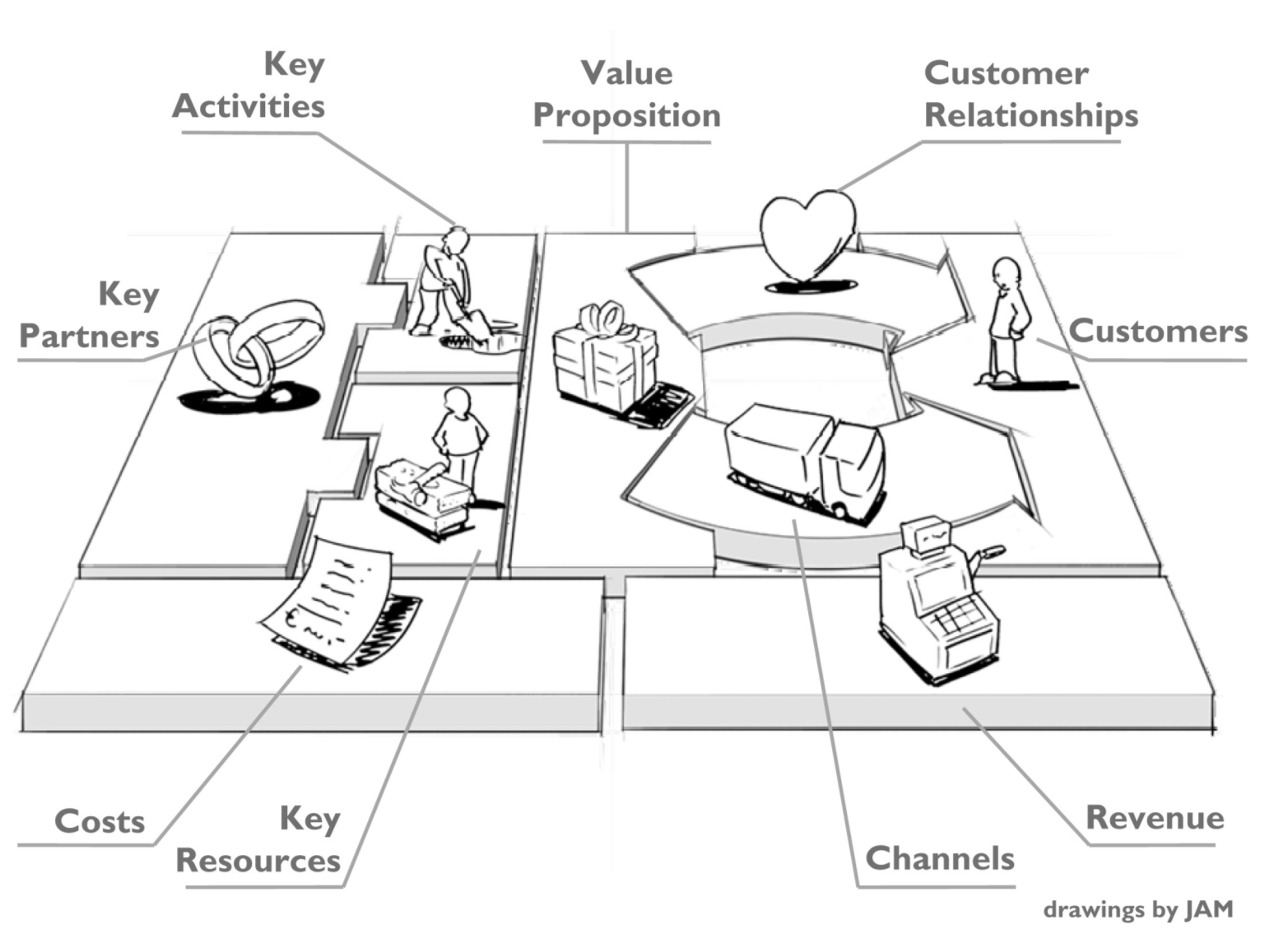

The theoretical arguments supporting different representations of business models have been in play for many years, yet it was Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur’s simple-to-use methods and tools described in their book Business Model Generation that popularized the Business Model Canvas (see Figure 4) and established it as the baseline for business model innovation. We use this form to show business model alignment between strategy and Business Architecture, followed by a deeper look in Appendix A. Note this type of business model has been introduced in earlier work of The Open Group through the IT4IT Forum.[3]

(Source: Business Model Generation, Alexander Osterwalder, Yves Pigneur, 2010)

Figure 4: The Business Model Canvas

Business and IT leaders can obtain powerful leverage using business model artifacts in conjunction with other strategic planning artifacts, Business Architecture views, and organizational change methods to accelerate strategic execution and alignment. Business model artifacts highlight the critical relationships between the various elements that constitute a business in ways that:

- Are not fully covered by other approaches or techniques and, therefore, contribute to a more complete examination of costs, revenues, and other business perspectives

- Are covered by other approaches or techniques – but through a different method or viewpoint – in which case business modeling helps cross-check other points of information and assumptions

Business models improve communication among business executives because they provide a common perspective for the organization’s core business logic, thus helping executives “get on the same page”. Having this common perspective, structure, and understanding allows for more effective business design[4] and enables the successful deployment of an organization’s target-state Enterprise Architecture. In essence, business models provide clarity of thought using a different point of view from the one provided by traditional strategic planning methods, and can foster a greater level of thinking required for innovation.

Business models provide a high-level visual representation of the current-state and/or future-state design of a business. They describe the rationale for how an organization creates, captures, and delivers value to its various internal and external stakeholders.

Business models also provide a basis for establishing a common understanding of how to describe and manipulate the business in pursuit of new strategic alternatives. In that sense, business models are a starting point for discussions around business innovation and strategy planning for the allocation of resources.

The development of a business model is initially performed at a relatively abstract or conceptual level. Maintaining this summary view encourages and enables the creative thought process that underpins innovation. It also helps to communicate key ideas about the vision and strategy to a broad audience, at a level that is appropriate to generate cross-disciplinary discussion and promote buy-in.

Usually there is just enough information available in a draft business model for interested parties to explore overall feasibility and support strategic decision-making. On the other hand, the sketch view does not normally contain sufficient information to perform a risk assessment or to develop a plan to execute the agreed strategy.

While the business model creates alignment for achieving business strategy, it is the Business Architecture that articulates the different perspectives and impacts of the business model. Business Architecture breaks the business model down into the core functional elements that describe how the business works, including the business capabilities, value streams, organizational structure and information objects required to deliver the desired business result. This process can also identify gaps and conflicts in the thinking and assumptions used to create the business model. In doing so, it can loop the discussion back to any required changes or improvements to the business model.

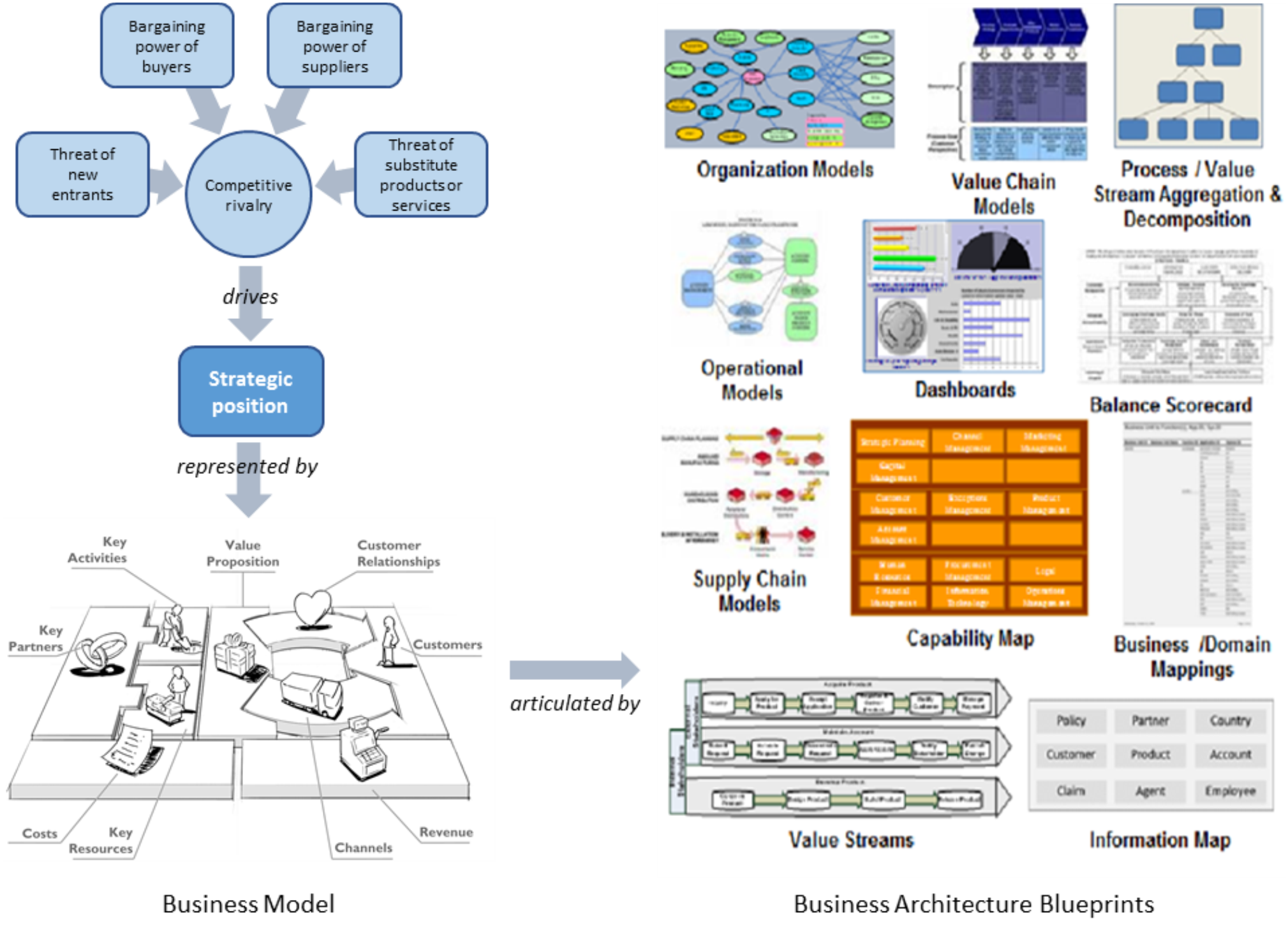

In the TOGAF Standard, Phase B: Business Architecture is where architects take the high-level business model artifact and develop a detailed set of architecture blueprints (representing different viewpoints of the proposal) to enable more in-depth planning, investment, and option analysis (see Figure 5). These detailed perspectives are useful and necessary for planning teams, business analysts, and business unit managers to understand and evaluate the overall impact of the proposed business model on the operation.

(Source: (top-left) The Five Competitive Forces that Shape Strategy, Michael E. Porter, 2008; and (Business Architecture Blueprints) BIZBOK® Guide, Version 6.5, 2018)

Figure 5: Relationships between Strategy, Business Models, and Architecture

The physical process of constructing a business model artifact presents a great opportunity for the architect to bring strategic perspectives of the enterprise into strategy formulation and business planning activities. In this case, the architect and the models they create bridge the gap between strategy and architecture. This helps to:

- Improve the alignment of Enterprise Architecture to strategy

- Elevate the overall quality of the architecture

- Increase the knowledge and value of the architect to the organization

Business models can be a key input into Phase B: Business Architecture of the TOGAF ADM. As such, they are normally associated with the Architecture Vision phase of Enterprise Architecture development. The business model is highly effective at aligning members of the leadership team around new strategies or a different business direction. The Business Architecture is more effective at aligning the rest of the enterprise on what needs to be done (and how) at an operational and organizational level:

- First, planners and architects use the business model to identify key partners that are stakeholders in the change

The business models are analyzed to gain insight into additional stakeholders, and their concerns, objectives, and key business requirements.

- Next, the business models are used to verify the business goals, strategic drivers, and constraints of the organization

Any inconsistencies or gaps are provided as feedback to the sponsors of the architecture statement of work for clarification.

- Architects then analyze the business models and use capability mapping to identify new capabilities (or enhancements to existing ones) that are required to realize the target business model

Architects also use value stream mapping to identify new value streams (or gaps in existing value streams) that must be developed to produce the value items described in the business model value propositions.

- Having assessed the capability gaps and future requirements, the target business models can be used to define the scope of the architecture statement of work in greater detail

They offer insights as to the breadth and depth of the architecture efforts. During this scoping step, the architecture is partitioned and aligned with the organization’s business models to ensure alignment of the architecture to strategy and value.

- The business models help to formulate architecture and business principles

For example, an organization shifting to a model that requires greater orchestration of the customer experience may benefit from establishing business principles for managing customer-centered solutions and handling customer information at different touch points.

- The business models provide an anchor for the development of the architecture project value proposition

An architecture project value proposition that demonstrates close alignment to the business model value proposition provides a powerful business case for the project.

- Finally, the business models facilitate the detailed statement of work and approval of the architecture project

This analysis provides a better understanding of the business problem at hand and offers insights into the nature, scope, and effort required for the architecture project.

Business models are part of the Architecture Vision inputs to the Business Architecture phase of the TOGAF ADM where they serve to help describe the business problem and scope of work of the Business Architecture phase, provide the business value context for the Business Architecture target description, and provide a means to align the Business Architecture to strategy and value:

- Planners and architects use the business models to understand the essential business problem and the vision of the change being proposed

- Business models help determine the Business Architecture statement of work and the types of Business Architecture models or artifacts required

For example, a company that envisions a business model that expands its existing product offering through new delivery channels to new customers may not require updates to the existing product catalog or product lifecycle diagrams.

- Business Architects utilize the business models as context and a starting point for baseline and target Business Architecture development

- Transition business models, if available, are valuable inputs to creating transition Business Architectures and business roadmaps

Business models help keep initiatives focused on the organization’s value-producing logic during the remainder of the TOGAF ADM phases. In the Information Systems Architecture and Technology Architecture phases, they can help planners and architects to maintain orientation of the architecture effort to the organization’s vision for value creation and exchange. During the Opportunities & Solutions and Migration Planning phases, business models, companions to the business roadmap produced in the Business Architecture phase, provide context for the development of architecture roadmaps, and implementation and migration plans.

Finally, because business models speak the language of the business and are validated early, they serve as an effective tool to communicate traceability of the architecture and solutions to the organization’s strategy. This greatly facilitates stakeholder engagement.

In order to steer the business in the face of constant change or to intentionally disrupt the market, business strategists are starting to use business models to identify new opportunities for innovation. Like other architecture disciplines, a designed structure that helps align leaders on the big shifts in revenue streams, costs, customer segments, and value propositions will improve the chances of success for any new strategy formulation.

Classically, business innovation has focused on product development or on process optimization. Businesses are increasingly recognizing that there are other aspects of the enterprise that offer more lucrative opportunities for improvement. For example, revenue streams (moving customers to subscription models rather than one-time purchases), value propositions (emphasizing service rather than just the physical product), cost structures (streamlining the supply chain), or channels (moving to online channels and reducing the physical footprint). Business model analysis enables this kind of innovation by explicitly calling out other aspects of the business around which more significant opportunities to improve business outcomes may exist.

Business model innovation involves taking a proposed business model or models from ideation to implementation in line with an overall business strategy. Using a design-oriented approach, business model innovators first construct observations about their environment and the organization’s position within that environment, including a description of the current-state business model. Then they develop and test a set of hypotheses using alternative future-state business models. They may design working prototypes of those business models in order to test and validate assumptions.

Most importantly, business model innovators use test results to confirm or reject the hypotheses and adjust or iterate the business model prototypes accordingly. Finally, they select the optimal business model (or models, as required to address different customer groups and value propositions within a single business) and describe them in sufficient detail through the Enterprise Architecture to support planning, development, and deployment.

While it might be a relatively easy task to conceive a new business model, implementing it and then continuously adapting it are not so easy. However, in the current environment of constant and rapid change, implementation and adaptation are exactly where successful organizations need to excel. It is not sufficient to establish a business model and then stop there; companies must constantly re-evaluate and redefine basic precepts including:

- What the company currently does

- How the company does it

- What the company could do

- How the company could do it

- With whom the company should do it

- How each piece interacts with parts of the company’s business ecosystem and the world at large[5]

The last point is particularly significant. When constructing a business model, organizations should ensure that they design and build all elements of that business model for agility so as to enable the business to thrive in a state of constant motion.

We will now use a specific type of business model framework – the Business Model Canvas – to provide a use-case. Appendix A provides a deeper definition of the structural elements in the canvas and how to interpret them. The starting place to build a model in the canvas depends on the organization and the desired usage for describing business value. Our use-case will take us through a retail business, which relates to the examples previously used in the TOGAF Series Guides to Business Capabilities and Value Streams (see Referenced Documents).

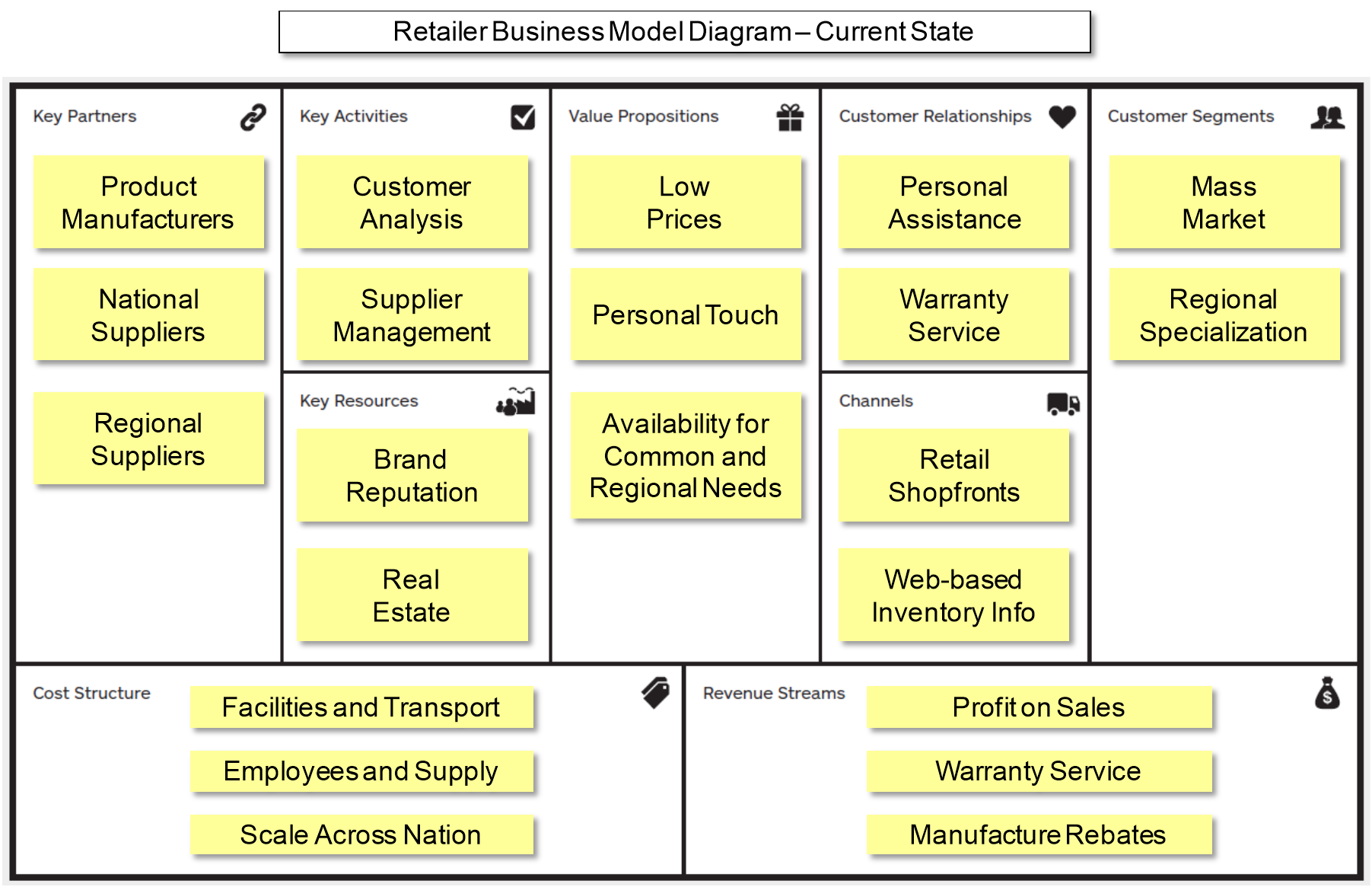

In Figure 6, we have a generic representation of a retail business model in its current state, meaning it represents how the business has been delivering value for the last several years. One way to understand the model is to read from the customers’ perspective – right-to-left – seeing how the business strives to serve both a mass retail shopper market and provide some regional specialization; provides both personal and sustained services; and gives shoppers both physical store shopfronts and the ability to find inventory ahead of time through the Internet. The business intends to provide greater value than the competition through lower prices, personalized help, and a better product range. To achieve this, they must have strong customer analytics, maintain their brand and facilities, and keep strong partnerships that lead to the right products through the right suppliers to meet those customer needs.

Figure 6: Retailer Business Model Canvas – Current State

Next we look at a situation that could lead to a change in the business model. The business may need to make significant changes due to market pressures, reduced sales, or increasing costs, or it may want to introduce new products or services to address unmet customer needs. A common guideline is that a truly new business model comes from a combined shift in customer segments and value proposition; anything narrower or on a smaller scale is merely an adjustment to the current business model.

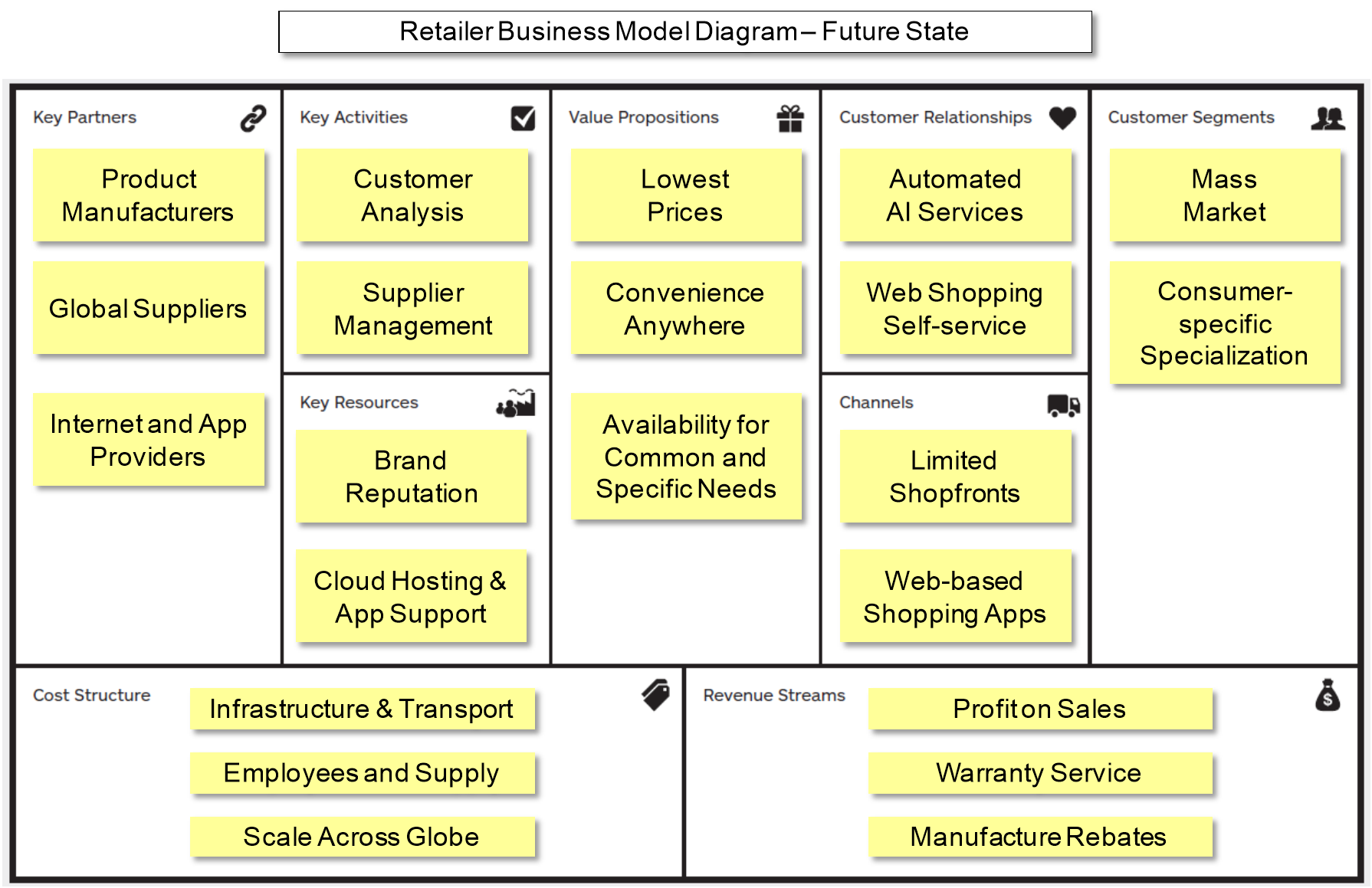

In the future-state model (see Figure 7), we see shifts in both the revenue-generating side of the canvas (increased specialization with specific customers, more online and digital presence, targeted value at the lowest possible cost) and the cost side (digital technologies being a key cost driver, a need for new partnerships, plus the global impacts on partnerships and costs). Some areas, such as key activities and sources of revenue, don’t change. Forming a new business model like this is a very people-oriented process, ideally based on good market, product, and cost data, but with leaders reaching alignment on how the business will deliver the most value in the future.

Let’s focus on the potential role of the architect and the Business Architecture methodology involved in helping leadership make this journey. The retailer has decided to pursue a new business model based on sound market trends and competitive imperatives (addressed on the revenue-generating or right-hand side of the canvas), but lacks a clear understanding of how value is truly delivered to stakeholders. Value streams can help provide that exact understanding, which then lead to identifying key business capability gaps that in turn define the required changes to the cost (left-hand) side.

Figure 7: Retailer Business Model Canvas - Future State

As examples of these relationships:

- The shift in the business model’s direction drives a need to reassess the “Acquire Retail Product” value stream as shown in the TOGAF Series Guide to Value Streams (§4.1), where the value stages may stay the same but some of the stakeholders, criteria, and value items will be affected

- Value may now be delivered to the customer from all five value stages when customers are located anywhere in the world, including finding products specialized to their local needs

- The changes to internal resources and partnerships (digital technologies as a key cost and source of new partnerships) could lead to critical business capability gaps to support value delivery, as detailed in the TOGAF Series Guide to Business Capabilities (§4.2); e.g., there may be gaps in Product Marketing that must be addressed to support a digital presence that includes online and mobile shopping, along with other new requirements caused by the desire for more global scale and partnerships

Businesses are turning more towards the use of business models as a key component of their strategy design and innovation processes. A business model by itself, however, does not provide sufficient granularity for organizations to construct detailed plans to realize those strategies. That is where Business Architecture plays a critical role in articulating and enabling the designs prompted by a business model.

This Guide demonstrates that business model innovation combined with Business Architecture provides planning teams with a more sophisticated set of options for moving from strategy through to actionable deployment. In doing so, it underscores the crucial role that business models can play in the effective execution of business strategy, while highlighting a number of opportunities to increase their use and effectiveness as an everyday business tool.

The framers of the Business Model Canvas purposefully created it to be an elegant, one-page representation of a business model that:

- Provides a shared perspective and understanding of an organization’s business model(s)

- Enables informed discussion among business executives on business issues and necessary change

- Fosters a design-oriented approach to identify what a business can do differently to maximize value exchanges between market participants

- Enables collaboration and co-creation of current-state and future-state business model options

- Focuses on the key revenue and cost components supporting an agreed value proposition for a particular customer segment

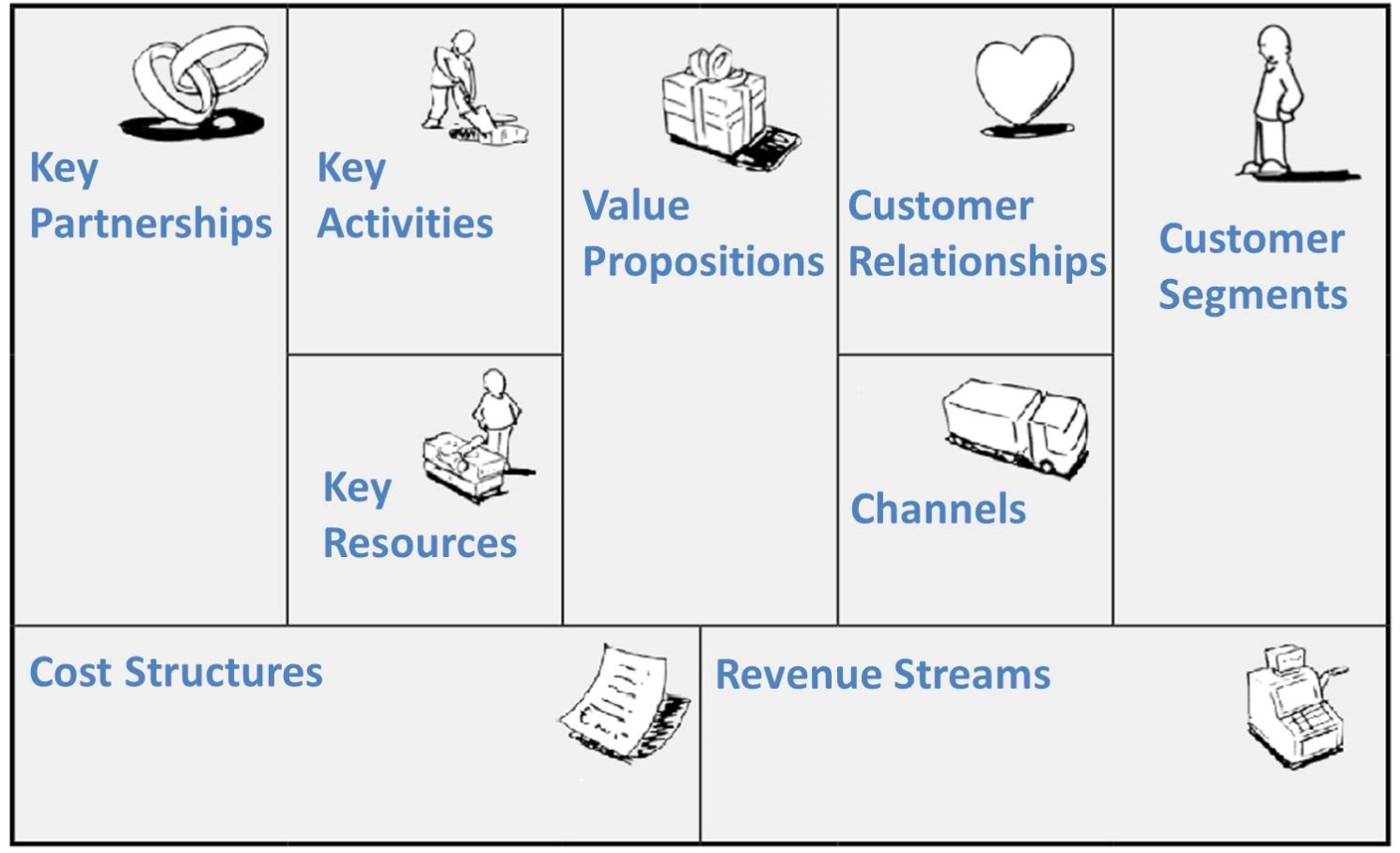

The Business Model Canvas includes nine building blocks, as depicted in Figure 8:

- Customer Segments – the different groups of people or organizations an enterprise aims to reach and serve

- Value Propositions – the benefits customers can expect from products and services

- Channels – how a company communicates with and reaches its Customer Segments to deliver a Value Proposition

- Customer Relationships – the types of relationships a company establishes with specific Customer Segments

- Revenue Streams – the revenue a company generates from each Customer Segment

- Key Resources – the most important assets required to make a business model work

- Key Activities – the most important things a company must do to make its business model work

- Key Partnerships – the network of suppliers and partners that make the business model work

- Cost Structures – all costs incurred to operate a business model

Figure 8: The Business Model Canvas[6]

The Business Model Canvas is a particularly useful tool for understanding how a business handles its key determinants of revenue and cost, the value proposition it uses to go to market, the customers it serves, and the resources it needs to execute. These elements play a crucial step in laying the framework for:

- The business case to move forward

- The remaining work to address the specific application, information, and technology solutions

- Achieving alignment between the business strategy and deployment plans

Identifying and working with a clearly articulated business model that supports the goals and objectives of the organization is a critical success factor for executing strategy – from inception to deployment. The Business Model Canvas can help expose capability gaps that exist with a proposed business model to assist strategists in charting the necessary course of action.

Footnotes

[1] See the referenced Business Model Generation, p.14.

[2] Linking Business Models with Business Architecture to Drive Innovation, A Business Architecture Guild White Paper, August 2015.

[3] Defining the IT Operating Model, White Paper published by The Open Group, September 2017 (see Referenced Documents).

[4] What is Business Design?, Rotman DesignWorks, 2015.

[5] From The Age of the Platform by Phil Simon, 2011.

[6] A. Osterwalder, Yves Pigneur et al, Business Model Generation (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2010. Page 14).

return to top of page

return to top of page