6 Architecture Governance

The development and use of EA must be governed.

This Guide now turns to the enterprise’s approach to decision-making, direction, and control. It discusses the process of governance, roles, and responsibilities as they pertain to the architecture process model in Chapter 10 (Process Model). Governance (decision-making, direction setting, and control) is addressed so early in this Guide to have clarity on the objectives. From this point onward, every action a Leader takes should be validated against this objective to stay relevant and focused on the outcome – not the ceremony of activities to be performed. A Leader should be very clear on what to report and to whom.

It is likely that the existing governance and support models of an enterprise will need to change to obtain the most value from the EA Capability. Understanding the enterprise’s required architecture governance requires the following questions to be answered:

- What is the reporting framework?

- What is the decision-making approach?

- What is the risk management approach?

- What is the enterprise’s approach to governance?

It is important to understand that governance applies to the development of a target architecture, how that target architecture governs change, and how the target architecture evolves.

6.1 Introduction to Governance

ISO/IEC 38500:2015[19] defines governance as: “a system that directs and controls the current and future state”. The process by which direction and control is provided should take into account equality of concern and transparency, protecting the rights and interests of the business.

Governance is a decision-making process with a defined structure of relationships to direct and control the enterprise to achieve stated goals. The key difference between governance and management rests on the cornerstone of fiduciary and sustainable responsibility. To define a customized governance approach, let us start to define the following:

- What is to be governed?

- Why should something be governed?

- When and who should decide on the recommended alternatives?

- How does this link to the EA process discussed in Chapter 10 (Process Model)?

Common mistakes to avoid are “fixing the blame” and “warned you before” processes and allowing weak policies that are focused on narrow-minded interests instead of securing the interests of the enterprise.

6.1.1 Key Characteristics

The following characteristics have been adapted from Corporate Governance by Ramani Naidoo[20] and are positioned here to highlight both the value and necessity for governance as an approach to be adopted within organizations and their dealings with all involved parties:

- Discipline: all involved parties will have a commitment to adhere to procedures, processes, and authority structures established by the enterprise

- Transparency: all actions implemented and their decision support will be available for inspection by authorized enterprise and provider parties

- Independence: all processes, decision-making, and mechanisms used will be established so as to minimize or avoid potential conflicts of interest

- Accountability: identifiable groups within the enterprise – e.g., governance boards who take actions or make decisions – are authorized and accountable for their actions

- Responsibility: each contracted party is required to act responsibly to the enterprise and its stakeholders

- Fairness: all decisions taken, processes used, and their implementation will not be allowed to create unfair advantages to any one particular party

Governance is about a hierarchy of decision-making that everyone commits to. Governance can be used to drive a set of behaviors. The act of observation by the governance team should not change the fact or how something is done. An observation results in some form of measurement. Define a set of measurements and metrics that can be used to achieve organizational objectives. Being transparent about why the measurement is being made and what mitigation options are available will drive positive behavior. Revisit the previous chapter to fine tune what to measure and why that measurement is needed.

Identify and define appropriate governance tiers to align what, how, when, and which tier gets escalated for relief. Absence of relief within each tier will result in loss of effective control and local autonomy. In general, lower tiers tend to be tactical in scope. Cross-cutting or higher tiers constrain lower tiers.

It is likely that the enterprise already has processes defined for some or all of the tiers shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Potential Governance Tiers

6.2 Essential Governance

A common failure pattern is to establish an EA governance board that believes it maintains decision rights about the target architecture, change to the architecture, relief, and enforcement. Decision rights about the target architecture, relief, and enforcement are always vested in the architecture’s stakeholders. Successful teams providing the EA Capability make sure that even within the lowest tier (technology architecture governance), stakeholders own the decision rights. An EA governance board owns process, and a recommendation regarding completeness and confidence in the work that led to the target architecture.

The short decision-tree checklist for an EA board to require an architect to answer when assessing a target architecture is given below. Note that it may sound natural to start anywhere on this checklist or pursue answers to these questions simultaneously. Experience has shown this approach to create more work than making governance invisible; however, it has proved to be effective. Notice the choice of words at the beginning of the paragraph. This is a “decision-tree” presented in free flow text format for readability. All questions are mandatory. As in any decision-tree, a negative response may force you to re-enter the tree at a higher level.

- Were the correct stakeholders identified? Y/N

— If yes, proceed

— If no, direct the architect to engage with the stakeholders appropriate to the scope of the architecture being developed

- Were constraints and guidance from superior architecture taken into account? Y/N

— If yes, proceed

— If no, either exercise architecture governance to change superior architecture, obtain relief, or enforce the architecture by directing the architect to take into account guidance and constraints from superior architecture

- Do appropriate subject matter experts agree with the facts and interpretation of the facts in the architecture? Y/N

— If yes, proceed

— If no, either direct the architect to engage with the subject matter experts or develop a recommendation for the stakeholders that they should have limitations in confidence

- Do any constraints or guidance produced reflect the views produced for stakeholders and any underpinning architecture models and analysis? Y/N

— If yes, proceed

— If no, direct the architect to do their job

- Do the views produced for the stakeholders reflect their concerns and reflect any underpinning architecture models and analysis? Y/N

— If yes, proceed to the stakeholders for approval

— If no, direct the architect to develop appropriate views

- Do the stakeholders understand the value, and any uncertainty in achieving the value, provided by reaching the target state? Y/N

— If yes, proceed

— If no, direct the architect to develop appropriate views and return to the stakeholders

- Do the stakeholders understand the work necessary to reach the target state and any uncertainty in successfully accomplishing the work? Y/N

— If yes, proceed

— If no, direct the architect to develop appropriate views and return to the stakeholders

- Do the stakeholders understand any limitations in confidence they should have in the target architecture? Y/N

— If yes, proceed

— If no, direct the architect to develop appropriate views and return to the stakeholders

- Have the stakeholders approved the views? Y/N

If the answer to the last question is yes, the EA board should approve the architecture for publication in the EA repository as the approved target architecture. Because the failure pattern is so embedded in practice we will re-iterate: there is no role for the EA governance board to debate, or approve, the contents of the target architecture and its constraints or guidance.

If the answer to the last question is no, the EA board should make a decision to either direct the architect to re-work the architecture usually through more advanced trade-off, or more often embracing the stakeholders’ preferences, or cancel the architecture initiative.

When the architecture is being used, changes to the enterprise are being guided, or constrained. Two factors impact governance of change. First, organizations operate in a dynamic environment, and the analysis of the target architecture cannot have assessed every circumstance or change option possible. Second, the target was produced for a purpose and may not have been developed to the level of detail required for the current use. The governance process requires the ability to change the architecture, provide relief from constraint, and enforce the architecture.

The role of EA governance is to manage the process of assessing compliance. All change is subject to compliance reviews against the constraints and guidance in the target architecture. Typically, these assessments are performed on a periodic basis to assess the operationally changing current state, and associated with a project to assess project-driven change. Where there is non-compliance, the stakeholders have three choices: first, enforce compliance; second, provide relief; and third, change the target architecture.

The short checklist for an EA board to require an architect to answer when assessing a non-compliance report is:

- Did the organization embarking on a change reasonably interpret the target architecture’s guidance and constraints? Y/N

— If yes, their interpretation should be accepted as compliance and any issues addressed through a change to the architecture

— If no, proceed

- Do appropriate subject matter experts agree with the facts and interpretation of the facts in the impact assessment? Y/N

— If yes, proceed

— If no, either direct the architect to engage with the subject matter experts or develop a recommendation for the stakeholders that they should have limitations in confidence

- Do appropriate subject matter experts agree with the recommendation to enforce the target, grant time-bound relief, or change the architecture? Y/N

— If yes, proceed

— If no, either direct the architect to engage with the subject matter experts or develop a recommendation for the stakeholders that they should have limitations in confidence

- Do the views produced for the stakeholders reflect the impact assessment and reflect any underpinning architecture models and analysis? Y/N

— If yes, proceed to the stakeholders for approval

— If no, direct the architect to develop appropriate views

- Do the stakeholders understand any limitations in confidence they should have in the impact assessment? Y/N

— If yes, proceed

— If no, direct the architect to develop appropriate views and return to the stakeholders

- Do the stakeholders understand the impact on prior expected value, and any change in certainty in achieving the value, provided by reaching the target state? Y/N

— If yes, proceed

— If no, direct the architect to develop appropriate views and return to the stakeholders

- Have the stakeholders approved the recommendation to enforce the target, grant relief, or change the architecture? Y/N

If the answer to the last questions is yes, the EA board should approve the non-compliance action recommendation for publication in the EA repository. Because the failure pattern is so embedded in practice, we will re-iterate: there is no role for the EA governance board to debate, or approve, the recommendation. Lastly, where relief is provided, the EA board should ensure that future compliance assessment and reporting take place to review time-bound relief. Without this step the enterprise has simply agreed to change the target architecture without the bother of an approval.

If the answer is no, the EA governance board has a difficult decision. In short, either the architect must be directed to expand the information provided to the stakeholders, or re-work the recommendation to embrace the stakeholders’ preferences.

Design of the EA governance two essential practices must be done in the context of the enterprise’s existing governance, reporting, and ERM practices.

6.3 What is the Current Reporting Framework?

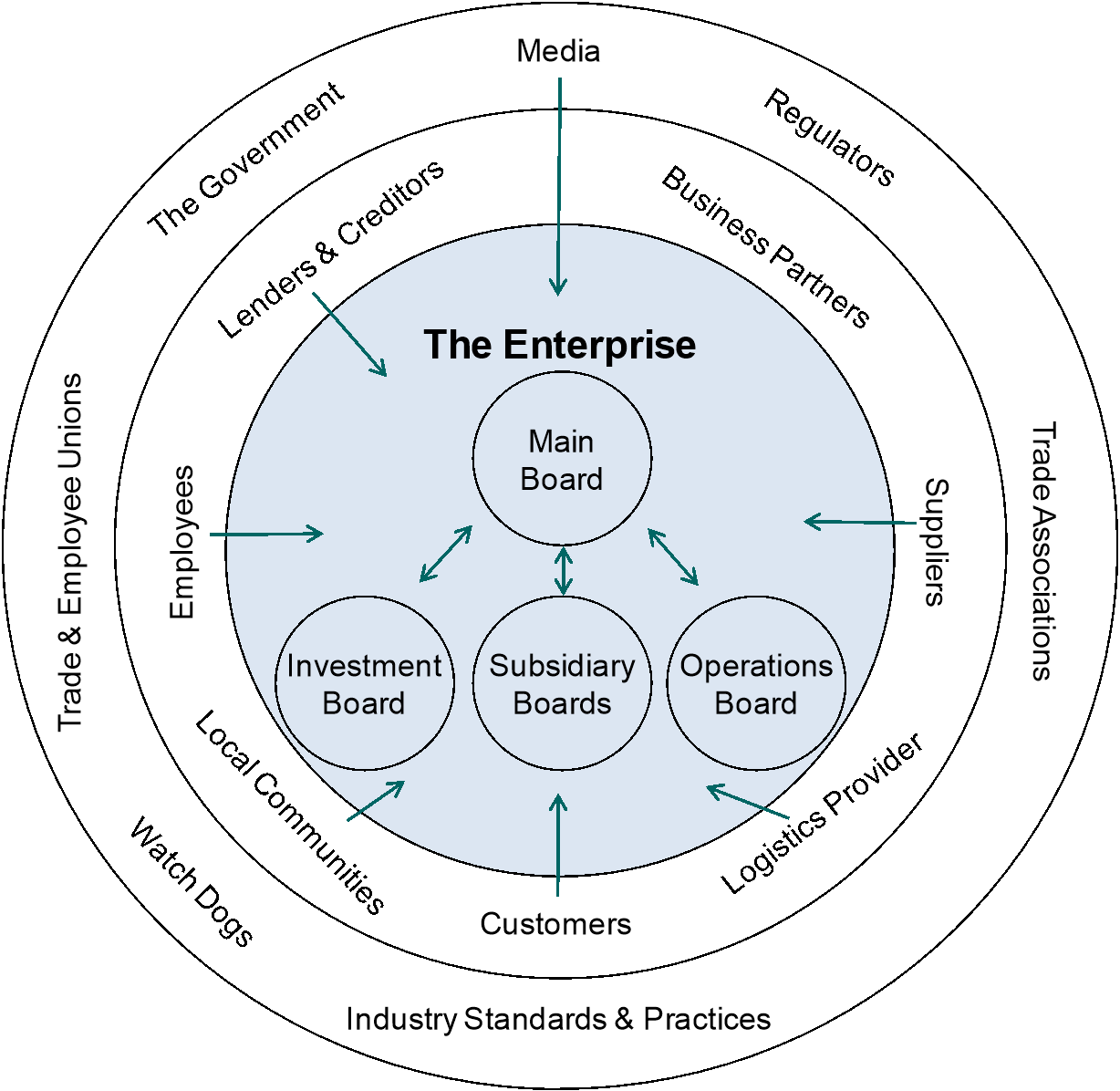

Redrawing the existing processes to showcase various interactions happening in an enterprise will help identify what should be governed. Figure 9 shows possible governance boards that exist in an enterprise to manage internal and external interactions. These interactions impact the business and hence the EA. These interactions result in exchange of information within and outside the enterprise, brokered via different mediums. Each kind of information dissemination or consumption could enable value or pose risk. The governance framework defines who will direct and control what kind of information exchange and when.

Figure 9: External and Internal Interactions Affecting Governance[21]

The governance framework should balance the needs of tactical and strategic operations of the enterprise. The enforcement responsibility and organizational level where enforcement happens will vary based on the charter for the EA Capability. The first step is to confirm the existence of existing governance mechanisms as shown in Figure 9, and determine which can be leveraged to include EA governance. At times, it may be possible to change the charter of an existing governance body to include architecture governance. In TOGAF terms, the architecture governance body is called the architecture board. The rest of the discussion in this chapter applies whether a Leader is creating a new or leveraging an existing body.

Governance is comprised of mechanisms, processes, and teams through which architects and stakeholders articulate their interests, exercise their legal rights, meet their obligations, and mediate their differences. The objective is to create a sustainable environment for inclusive and responsive processes to achieve the goals of the enterprise, mitigating all risks. To govern effectively and efficiently, basic policies, principles, and rules should be identified, created, and published. Having a set of architecture principles, standards, reference architectures, and best practice defined is useful. The principles defined should be commensurate with the size, complexity, structure, economic significance, and risk profile of the enterprise’s operations.

6.4 What is the Current Risk Management Approach?

A central role of the EA Capability is to facilitate creation of an environment where operational risk can be optimized for maximum business benefit and minimum business loss. This requires close integration with the enterprise’s risk management approach and an understanding of the scope and interests of Enterprise Risk Management (ERM). Tight integration with ERM facilitates tilting the EA to improve realization of objectives, and the reduction of uncertainty.

Consideration of ERM in the context of governance is driven by the foundation that governance is a decision-making process, with a defined structure of relationships to direct and control the enterprise to achieve stated goals. The process by which direction and control is provided should imbibe equality of concern and transparency, protecting the rights and interests of the business.

The most common understanding of risk is derived from Information Security Management (ISM), which is largely focused on mitigating threat and vulnerability. While ISM is important, a broad understanding of ERM is required. Detailed understanding of risk and risk management can be gained from The Open Group White Paper: TOGAF® and SABSA® Integration.[22]

Central questions that need to be answered are:

- What is the enterprise’s risk appetite?

- What is the enterprise’s risk tolerance?

Associated governance questions include:

- Who agrees to a risk assessment?

- Who agrees to a risk treatment plan?

6.4.1 What is Risk?

The heart of effective risk management is managing to the expected objective. Every activity, operational activity, and change activity has an element of risk that needs to be managed, and every outcome is uncertain. Risk management is about reducing uncertainty. The ISO 31000 Risk Management standard definition of risk is the “effect of uncertainty on objectives”. The effect of uncertainty is any deviation from what is expected.

Uncertainty typically involves a deficiency of information and leads to inadequate or incomplete knowledge or understanding. In the context of risk management, uncertainty exists whenever the knowledge or understanding of an event, consequence, or likelihood is inadequate or incomplete.

The EA Capability is focused on where the enterprise is going, and its path to change. A different future, and the changes required to realize such a future, are intertwined with the “effect of uncertainty on objectives”. This requires close integration with the enterprise’s ERM approach. Inherent in strong risk management is striking the balance between positive and negative outcomes resulting from the realization of either.

6.4.2 Core Concepts of Enterprise Risk Management (ERM)

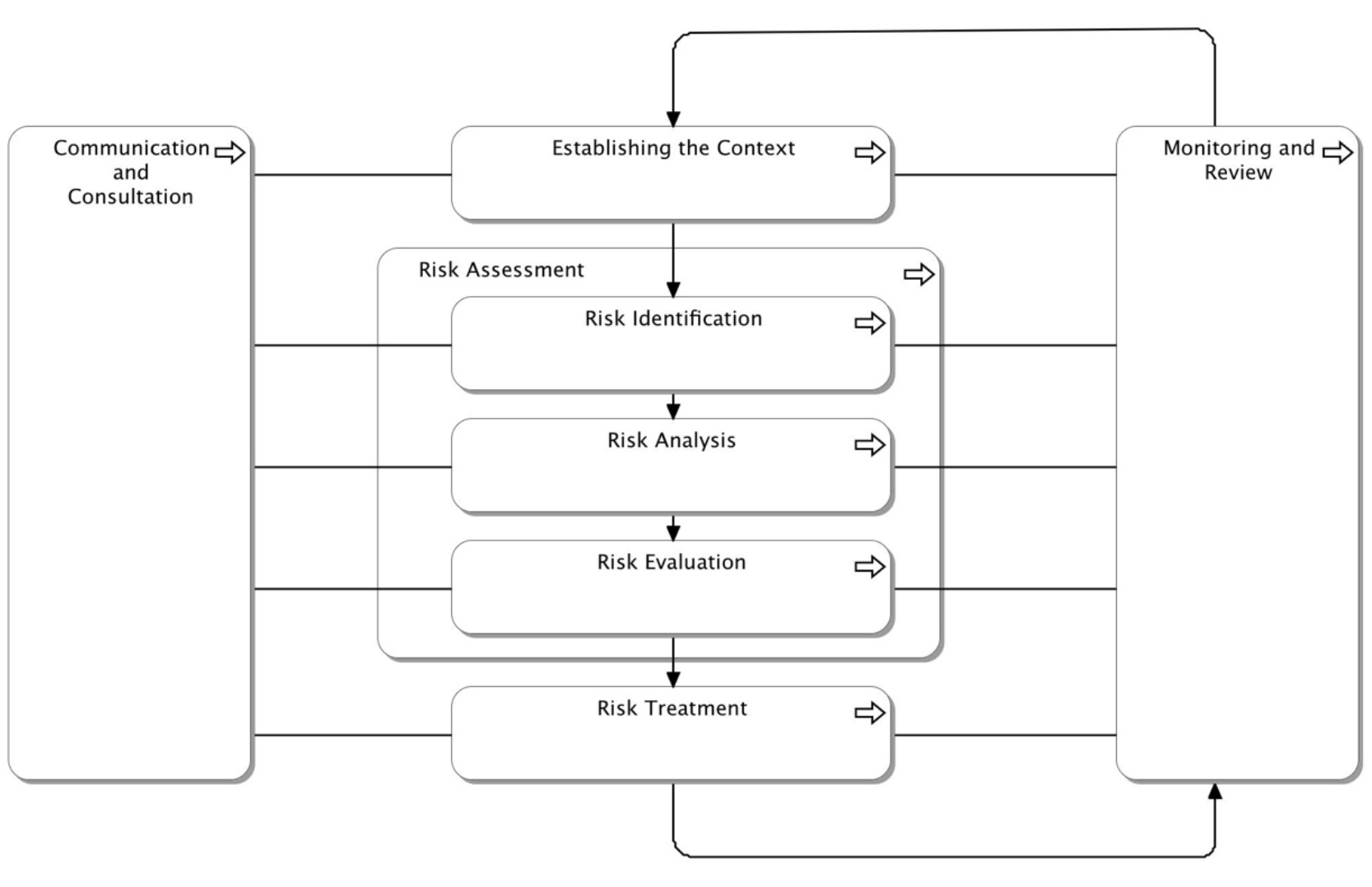

The definitive standard for Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) – the ISO 31000 standard – outlines a risk management approach to aiding decision-making by taking account of uncertainty and the effect of this uncertainty reaching the enterprise’s objectives. Following the ISO 31000 standard approach ensures that risk management is embedded deeply and firmly in all business activities. It also states that it is a continuous lifecycle rather than an isolated activity.

Figure 10: The ISO 31000 Standard Model for Risk Management[23]

6.5 Existing Governance Process

The process should be documented in such a way that information about when and which approval, enforcement, and relief mechanisms should be deployed should be as self-explanatory, transparent, and effective as needed. In selecting an existing governance body, consider the simplicity of process and its effectiveness.

At all levels of the governance process, it is essential that measurements, metrics, and rationale for relief be defined in business terms. Governing a portfolio by number of machines eliminated does not relate itself to a business outcome. Translate to something like cost optimization for the same operational capacity.

It is possible for a perception to exist in the enterprise that EA exists as an ivory tower or as an overhead organization, especially when EA is being re-booted after a failure. To not follow the rules in the first paragraph of this chapter would probably provide the reasons for such a perception. It is OK to go to market with full awareness and a plan for risk mitigation within the context of the enterprise’s appetite and tolerance for risk instead of recommending “stoppage” of work against a theoretically risk-free approach. It is better to be ahead of the curve and influence the selection of better and viable alternatives during the feasibility study or initiation of an effort. Define the governance process so that it can achieve delivery proactively.

Governance often results in a change, either to current effort or future efforts. Organizational and architecture change management should account for triggers and provide a timeline to implement the change from governance decisions. Imagine opening a faucet for hot water in the morning. Other control mechanisms sense the opening of the faucet, and it takes a while for the hot water to start flowing out of the faucet – flushing out the cold water in the line. Governance operates in a similar way at times, and its process should also account for long lead times for corrective actions to take effect.

All governance decisions and scope are not the same – for example, business architecture decisions will impact operational processes and cost, or when the goal has to be restated, scope of impact and governance decisions are the same. Nor will the level of decision-making – operational to strategic – impact the scope of change.

6.5.1 Definition of Roles

Roles define those who get to participate and their span of control in which tier should be identified and defined. Just like the differences in skill set and approach to developing architecture and managing architecture, there are differences in execution style between architecture governance and management. Architecture management involves the development of policies and standards and the recommendation of scenarios under which they should be applied. This keeps the governance body informed of the context of the impact of architecture in a concise format.

There is an important distinction in practice. The governance body approves the policies, standards, and rules recommended by the architecture management team for the EA Capability, but does not approve the architecture. Only the set of stakeholders can approve an architecture and roadmap. An EA Capability governance body focuses on ensuring the process was followed; the appropriate stakeholders were engaged, and the materials produced are internally consistent. It is the responsibility of the EA Capability Leader to differentiate the role of these functions and identify qualified personnel. It is common that the functional head of an EA Capability is not the head of the architecture governance body.

TOGAF® is a registered trademark of The Open Group

return to top of page

return to top of page