Project management

See also the PMBOK summary.

Project basics

We are already doing work, using Scrum and Kanban for the most part. But there is interest in more formalized, traditional project management, so some of you go to training and learn the following basics.

Let’s start with the most fundamental aspects of a project. You can start your understanding of a project by first thinking of a “to-do” list. However, rather than a miscellaneous list of errands, a project is a to-do list that is aimed at delivering some overall end result, with certain resources and within a time frame. So, in terms of your daily life, a random list of to-dos isn’t a project, but if you are organizing your annual holiday party, that certainly would qualify as a project.

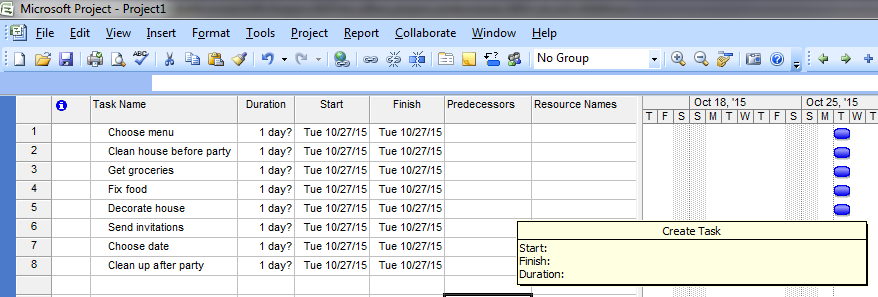

We could start with the following list:

Choose menu |

Clean house before party |

Get groceries |

Fix food |

Decorate house |

Send invitations |

Choose date |

Clean up after party |

One of the important characteristics of a project is that it is temporary. This project ends when we clean up after the party. Project management, however, takes things much further. There are a number of ways that the list above can be refined using project management techniques.

First, we should probably organize the list a little better. And the task “clean house” — do we understand precisely what we mean by that? Maybe we should break this down into sub-tasks. Also, you may notice that there are “dependencies.” For example, we can’t send out invitations before we choose the date, nor can we fix the party food before we get groceries, which in turn depends on setting the menu.

Let’s break out a tool. Introducing Microsoft Project (see Microsoft Project screenshot).

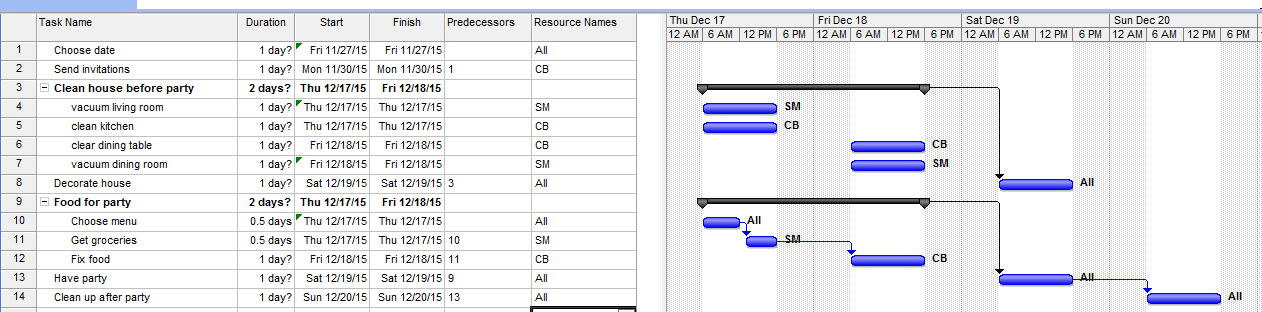

We put our list in it. Then, we set up some sub-tasks and document the dependencies. Notice the bold headings:

-

Clean house before party

-

Food for party

and how they have indented “sub-tasks” underneath them (see Project plan with sub-tasks).

These are all the things that need to be completed, for the overall major task to be considered complete. For example, we can’t call the house clean if the dining room isn’t vacuumed. Also notice that, to the right, we see certain tasks are linked by thin black arrows. We are not going to decorate the house until all the cleaning is done, and we need to get the food prepared before we have the party. As mentioned above, these are called dependencies.

This is just the tip of the iceberg. Much more can be tracked in a formal project management approach, such as:

-

Cost of people’s time — forecast and actual

-

% complete of a given task

-

Which sequence of tasks is the “critical path” — the sequence that must be done in order, that will take the longest time

PMBOK [214] defines the critical path as “The sequence of activities that represents the longest path through a project, which determines the shortest possible duration.” In the above example, we have two major work areas: clean the house and prepare a menu. Note however that there are no dependencies between:

-

vacuum living room

-

clean kitchen

-

clean dining table

-

vacuum dining room

Really, they can be done in any order.

On the other hand, there is a clear set of dependencies between:

-

Choose menu

-

Get groceries

-

Fix food

This means that the sub-activity “Food for party” is the critical path. If the menu is not determined on time, the grocery run can’t happen, and the food will be fixed late or not at all.

A project manager is responsible for all of this and more. A critical concept is that of "deliverable.” In this example, the deliverable is the outcome of each task:

-

invitations sent by 11/30 by CB

-

menu decided by 12/17 by all

-

house cleaned by 12/18 by all

-

food prepared for guests by 12/18 by CB

Notice that deliverables are defined by “what,” “who,” and “when."”

While it is the responsibility of each contributor to the project to “meet” their deliverables, the project manager checks in regularly with each of them as to whether they will in fact be able to do this. In larger, more complex projects, the project manager updates the project plan with the effort expended to date, and the estimated time to completion. Individual status reports are assembled (“rolled up”) into an overall picture of project status, reported to executives with a high level assessment of whether the project is likely to meet its objectives of cost, scope, quality, and schedule.