Domain-Specific Guidance

This chapter describes the guidance provided in the TOGAF Standard for specific topic domains.

Security Architecture

Documentation

| Document | Summary |

|---|---|

TOGAF Series Guide: Integrating Risk and Security within a TOGAF Enterprise Architecture |

This document provides guidance for security practitioners and Enterprise Architects to develop an Enterprise Architecture that comprehensively addresses risk and security. It describes how to integrate risk and security into an Enterprise Architecture, and introduces a common language for Security Architects and Enterprise Architects. |

Integrating Risk and Security

A Security Architecture is a structure of organizational, conceptual, logical, and physical components that interact in a coherent fashion in order to achieve and maintain a state of managed risk and security (or information security). It is both a driver and enabler of secure, safe, resilient, and reliable behavior, as well as for addressing risk areas throughout the enterprise.

However, an Enterprise Security Architecture does not exist in isolation. As part of the enterprise, it builds on enterprise information that is already available in the Enterprise Architecture, and it produces information that influences the Enterprise Architecture. This is why a close integration of Security Architecture in the Enterprise Architecture is beneficial. In the end, doing it right the first time saves costs and increases effectiveness compared to bolting on security afterwards. To achieve this, Security Architects and Enterprise Architects need to speak the same language. That language is introduced in the TOGAF Series Guide: Integrating Risk and Security within a TOGAF® Enterprise Architecture.

Definition of Risk

Risk is the “effect of uncertainty on objectives” (ISO 31000:2009).

The effect of uncertainty is any deviation from what is expected – positive and negative. The uncertainty is concerned with predicting future outcomes, given the limited amount of information available when making a decision. This information can never be perfect, although our expectation is that given better quality information we can make better quality decisions. Every decision is based on assessing the balance between potential opportunities and threats, the likelihood of beneficial outcomes versus damaging outcomes, the magnitude of these potential positive or negative events, and the likelihood associated with each identified outcome. Identifying and assessing these factors is known as “risk assessment” or “risk analysis”. “Risk management” is the art and science of applying these concepts in the decision-making process.

Security as a Cross-Cutting Concern

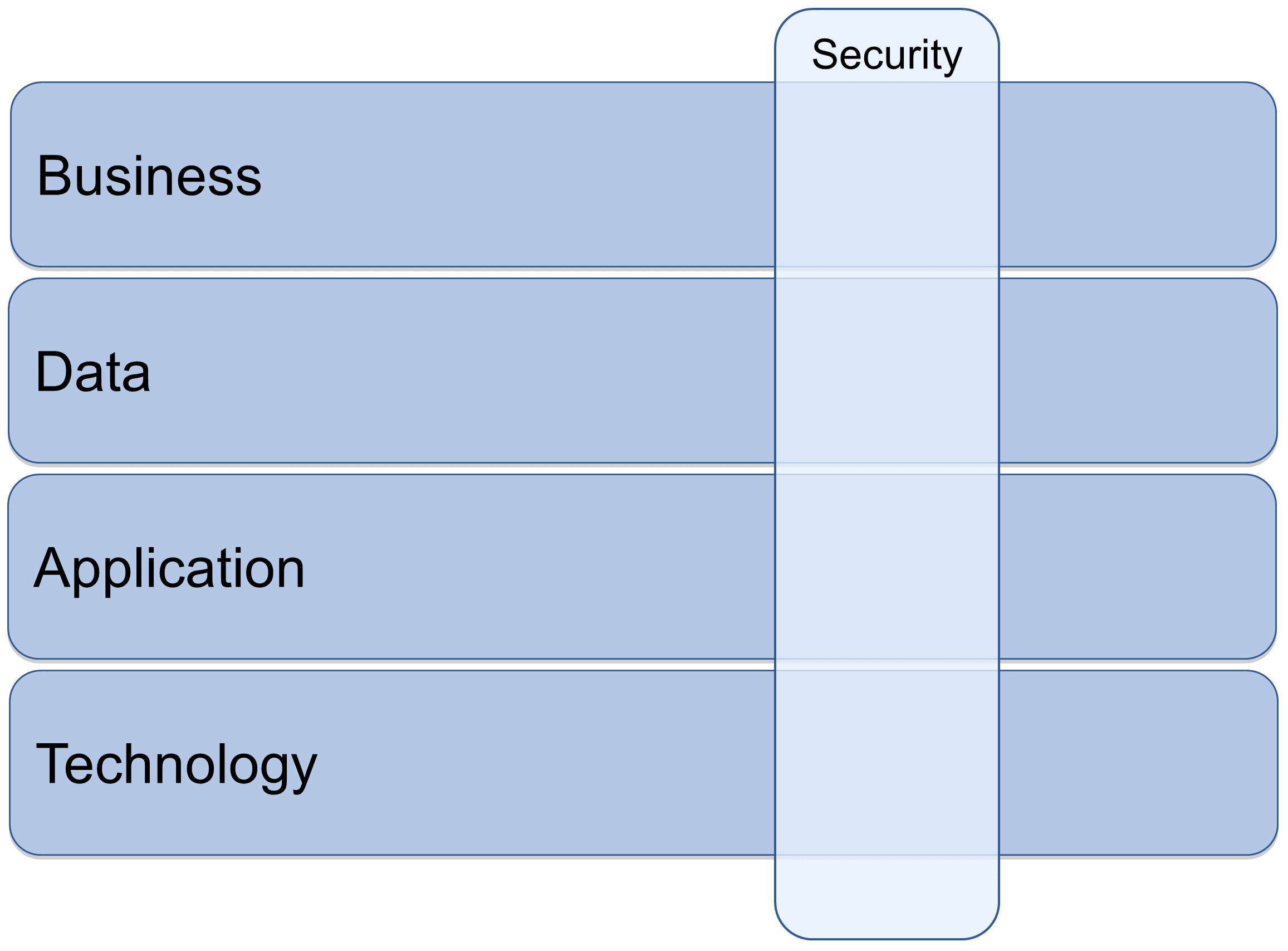

Security Architecture is a cross-cutting concern pervasive through the whole Enterprise Architecture. It can be described as a coherent collection of views, viewpoints, and artifacts, including security, privacy, and operational risk perspectives, along with related topics like security objectives and security services. The Security Architecture is more than a dataset; it is based on the Information Security Management (ISM) and Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) processes.

The TOGAF ADM covers the development of the four architecture domains commonly accepted as subsets of an Enterprise Architecture: Business, Data, Application, and Technology. As a cross-cutting concern, the Security Architecture impacts and informs the Business, Data, Application, and Technology Architectures (see Figure 1). The Security Architecture may often be organized outside of the architecture scope, yet parts of it need to be developed in an integrated fashion with the architecture.

Enterprise Risk Management

Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) aids decision-making by taking account of uncertainty and the possibility of future events or circumstances (intended or unintended) and their effects on agreed objectives. Risk management should be embedded deeply and firmly in all business activities. It is a continuous lifecycle rather than an isolated activity.

The following concepts are important for ERM:

-

Key risk areas

-

Business impact analysis

-

Risk assessment

-

Business risk model/risk register

-

Risk appetite

-

Risk mitigation plan/risk treatment plan

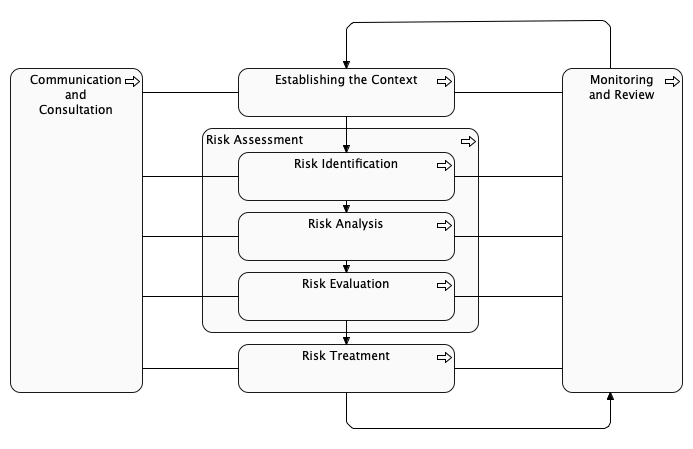

The ISO 31000:2009 risk management process model is shown in Figure 2.

Information Security Management

Information Security Management (ISM) is a process that defines the security objectives, assigns ownership of information security risks, and supports the implementation of security measures. The security management process includes risk assessment, the definition and proper implementation of security measures, reporting about security status (measures defined, in place, and working), and the handling of security incidents.

Business Architecture

The TOGAF Standard provides guidance for Business Architects and Enterprise Architects to develop an Enterprise Architecture that is based upon the business model, ecosystem, value, and organizational design the organization has and needs.

Documentation

| Document | Summary |

|---|---|

TOGAF Series Guide: Business Models |

This document provides a basis for Enterprise Architects to understand and utilize business models, which describe the rationale of how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value. It covers the concept and purpose of business models and highlights the Business Model Canvas™ technique. |

TOGAF Series Guide: Business Capabilities, Version 2 |

This document answers key questions about what a business capability is, and how it is used to enhance business analysis and planning. It addresses how to provide the architect with a means to create a capability map and align it with other Business Architecture viewpoints in support of business planning processes. |

TOGAF Series Guide: Business Capability Planning |

This document shows how an organization can introduce business capability planning or revise or refine existing efforts. It provides techniques, recommends tools, and provides references to other methods useful for business capability planning. |

TOGAF Series Guide: Value Streams |

Value streams are one of the core elements of a Business Architecture. This document provides an architected approach to developing a business value model. It addresses how to identify, define, model, and map a value stream to other key components of an enterprise’s Business Architecture. |

TOGAF Series Guide: Information Mapping |

This document describes how to develop an information map that articulates, characterizes, and visually represents information that is critical to the business. It provides architects with a framework to help understand what information matters most to a business before developing or proposing solutions. |

TOGAF Series Guide: Organization Mapping |

This document shows how organization mapping provides the organizational context to an Enterprise Architecture. While capability mapping exposes what a business does and value stream mapping exposes how it delivers value to specific stakeholders, the organization map identifies the business units or third parties that possess or use those capabilities, and which participate in the value streams. |

TOGAF Series Guide: Business Scenarios |

This document describes the Business Scenarios technique, which provides a mechanism to fully understand the requirements of information technology and align it with business needs. It shows how business scenarios can be used to develop resonating business requirements and how they support and enable the enterprise to achieve its business objectives. |

Business Models

A business model is a description of the rationale for how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value.

Business models provide a basis for establishing a common understanding of how to describe and manipulate the business in pursuit of new strategic alternatives. In that sense, business models are a starting point for discussions around business innovation and strategy planning for the allocation of resources. Business models can be represented in many different ways; for example, see the TOGAF Series Guide: Business Models.

The benefits of using business models include:

-

Improved communication

-

Providing a common perspective

What is a Business Capability?

A business capability is a particular ability or capacity that a business may possess or exchange to achieve a specific purpose or outcome.

A key point differentiating a business capability from say a business process, is that it delineates what a business does without attempting to explain how, why, or where the business uses the capability.

A business capability can be something that exists today or something that is required to enable a new direction or strategy. When integrated into a business capability map, business capabilities represent all of the abilities that an enterprise has at its disposal to run its business. A key distinction is that business capability components (the how) will change regularly, but that the business capability endures over longer planning horizons.

Defining a Business Capability

Naming the business capability is the first step in the capability definition process. It establishes a clear need for the existence of the business capability and helps to ensure it is clearly distinguishable from other business capabilities.

A brief description helps to clarify the scope and purpose of the business capability and to differentiate it from other business capabilities. As with the business capability name, it helps to write all descriptions using language that is relevant and appropriate to the business stakeholders. Two important considerations are to:

-

Be concise: provide just enough detail over one or two sentences to enable greater understanding than can be gained from the business capability name alone.

-

Be precise: do not simply repeat the name of the business capability in the description, such as “the ability to manage projects” when describing “project management”.

The template shown in Table 3 can be used to define an individual business capability.

Name |

This should be a noun (“this is what we do”) rather than a verb (“this is how we do it”). Business capabilities are most often written as compound nouns; e.g., “Project Management” or “Strategic Planning”. |

|

Description |

A brief description clarifying the scope and purpose and differentiating it from other business capabilities. A useful syntax is to phrase the description of each business capability as “the ability [or capacity] to …”. |

|

Components |

Roles |

Roles represent the individual actors, stakeholders, business units, or partners involved in delivering the business capability. Roles should be described in a way that is not organization-specific. |

Processes |

Identify just the core business processes within a business capability. Identifying and analyzing the efficiency of the core processes helps to optimize the business capability’s effectiveness. |

|

Information |

The business information and knowledge required or consumed by the business capability (as distinct from IT-related data entities). There may also be information that the capability exchanges with other capabilities. Examples include information about customers and prospects, products and services, business policies and rules, sales reports, and performance metrics. |

|

Resources |

The tools, resources, or assets that a business capability relies on for successful execution. Examples include IT systems and applications, physical tangible assets (buildings, machinery, vehicles, etc.), and intangible assets such as money and intellectual property. |

|

A business capability example, “Recruitment Management”, is shown in Table 4.

Name |

Recruitment Management |

|

Description |

The ability to solicit, qualify, and provide support for hiring new employees into the organization. |

|

Components |

Roles |

User:

Stakeholders:

|

Processes |

Evaluate New Hire Requisitions Recruit/Source Candidates Screen and Select Candidates Hire Candidate |

|

Information |

Candidate/Applicant Details Position Descriptions Recruitment Agency Data Industry Standard Role Definitions |

|

Resources |

Recruitment Management Application HR Application Social Media Application |

|

What is a Business Capability Model?

A business capability model represents the currently active, stable set of business capabilities (along with all of their defining characteristics) that cover the business, enterprise, or organizational unit in question.

The first task of business capability modeling is to capture and document all of the business capabilities that represent the full scope of what the business segment under consideration does today (irrespective of how well it does it) or what it desires to be able to do in the future. The second task is to organize that information in a logical manner.

The end product of the modeling process is typically a Business Capability Map, which provides the visual depiction (or blueprint) of all the business capabilities at an appropriate level of decomposition, logically grouped into different categories or perspectives to support more effective analysis and planning.

Strategic |

Business Planning |

Market Planning |

Partner Management |

Capital Management |

Policy Management |

Government Relations Management |

|

Core |

Account Management |

Product Management |

Distribution Management |

Customer Management |

Channel Management |

Agent Management |

|

Supporting |

Financial Management |

HR Management |

Procurement Management |

Information Management |

Training Management |

Operations Management |

Mapping Capabilities to Other Business Perspectives

Having identified and organized the business capabilities into a business capability model, it is then possible to apply the information to business analysis and planning.

There are two aspects to consider:

-

Adding a heat map to the business capability model itself.

-

Mapping the relationships between the business capabilities and other business and IT architecture domains, using cross-mapping techniques such as capability/organization mapping, and capability/value stream mapping (see Mapping Value Streams to Capabilities).

These are described in detail in the TOGAF Series Guide: Business Capabilities, Version 2 ![]() .

.

What is a Value Stream?

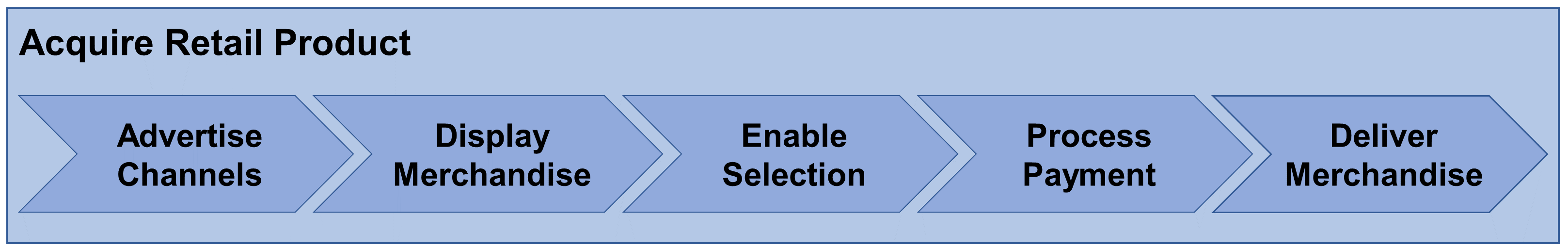

A value stream (a simple example of which is shown in Figure 3) is depicted as an end-to-end collection of value-adding activities that create an overall result for a customer, stakeholder, or end user. In modeling terms, those value-adding activities are known as value stream stages, each of which creates and adds incremental stakeholder value from one stage to the next.

Value streams may be externally triggered, such as a retail customer acquiring some merchandise, as shown in Figure 3. Value streams may also be internally triggered, such as a manager obtaining a new hire. Value streams may be defined at an enterprise level or at a business unit level. Either way, the complete set of value streams (as depicted in a value stream diagram or map) is simply the visual representation of all the value streams that denote an organization’s primary set of business activities. It is an aggregation of the multiple ways in which the enterprise creates value for its various stakeholders.

The Benefits of Value Streams

Mapping value streams as part of a broader Business Architecture initiative is a quick and easy way to obtain a snapshot of the entire business, since those value streams represent all the work that the business needs to perform – at least from a value-delivery perspective.

Doing so helps business leaders assess their organization’s effectiveness at creating, capturing, and delivering value for different stakeholders.

Defining a Value Stream

Name |

The value stream name must be clearly understandable from the initiating stakeholder’s perspective. In contrast to the way that business capabilities are named, value streams use an active rather than passive tense. That usually means a verb-noun construct. For example, “Acquire Retail Product” and “Recruit Employee”. |

Description |

While the value stream name should be self-explanatory, a short, precise description can provide additional clarity on the scope of activities with which the value stream deals. |

Stakeholder |

The person or role that initiates or triggers the value stream. |

Value |

The value (expressed in stakeholder terms) that the stakeholder expects to receive upon successful completion of the value stream. That value is an aggregation of the incremental value items that are delivered by each value stream stage. |

Continuing with the earlier example shown in Figure 3, we can define the value stream as shown in Table 7.

Name |

Acquire Retail Product |

Description |

The activities involved in looking for, selecting, and obtaining a desired retail product. |

Stakeholder |

A retail shopper wishing to purchase a product. |

Value |

Customers are able to locate desired products and obtain them in a timely manner. |

Decomposing a Value Stream

Value, as shown in a value stream, is achieved through a series of sequential and/or parallel actions, known as value stream stages, that incrementally create and add stakeholder value from one stage to the next.

It is possible to decompose a value stream by defining the value stream stages, as shown in Table 8.

Name |

Two to three words identifying what is (or will be) achieved by this stage. |

Description |

A few sentences explaining the purpose and the activities performed during the value stream stage. |

Stakeholders |

Actors who receive measurable value from the value stream stage, or who contribute to creating or delivering that value. |

Entrance Criteria |

The starting condition or state change that either triggers the value stream stage or enables it to be activated. |

Exit Criteria |

The end state condition that denotes the completion of the value stream stage; i.e., when the required value has been created or delivered to the stakeholders. This information becomes the entry criteria for the next value stream stage. |

Value Item |

The incremental value that is created or delivered to the participating stakeholder(s) by the value stream stage. |

Table 9 decomposes the earlier example, and lists the elements of each value stream stage, including a description, the participating stakeholders, entry criteria, exit criteria, and the value delivered from each stage. This retail example deals with physical storefronts as well as online sites, so the terms used could apply to either channel or type of customer interaction.

| Value Stream Stage | Description | Participating Stakeholders | Entrance Criteria | Exit Criteria | Value Item |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Advertise Channels |

The act of making customers aware of the company’s products. |

Store or Website Owner, |

Customer searches for product |

Customer selects channel |

Retail channel available to customer |

Display Merchandise |

The act of presenting products in a physical or searchable digital form. |

Store Employees, |

Customer selects channel |

Customer views products |

Product options provided to customer |

Enable Selection |

The act of enabling filtering and assessments of the best product(s) matched to the customer’s needs. |

Store Employees, |

Customer views products |

Customer selects product |

Desired product located |

Process Payment |

The act of taking and processing payment from the customer. |

Cashier, |

Customer selects product |

Charges paid |

Delivery commitment |

Deliver Merchandise |

The act of getting the product into the customer’s hands. |

Warehousing, |

Charges paid |

Product delivered |

Product in user’s possession |

Mapping Value Streams to Capabilities

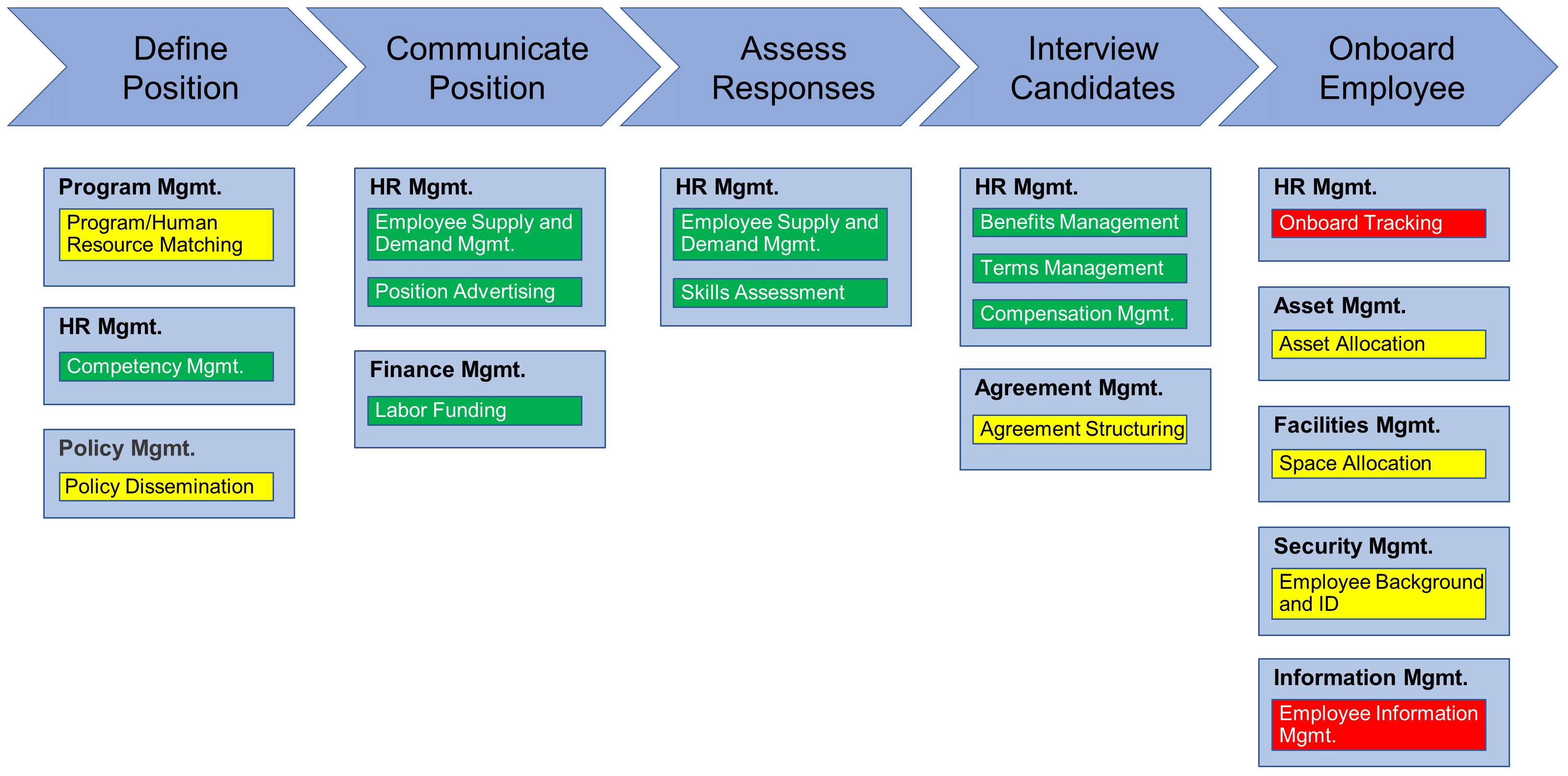

Figure 4 uses the Recruit Employee value stream from the TOGAF Series Guide: Value Streams to illustrate both mapping a value stream to business capabilities, as well as the use of a heat map. In this example an analysis has been made as to how well each business capability supports the required value to be delivered by the value stream stage, with green indicating a good match, yellow indicating some changes needed, and red indicating significant gaps between what is needed and what is present.

Information Mapping

information mapping provides the architect with a means to articulate, characterize, and visually represent the information that is critical to the business, and to shape its representation in ways that enable a more detailed analysis of how the business operates today – or how it should operate at some point in the future.

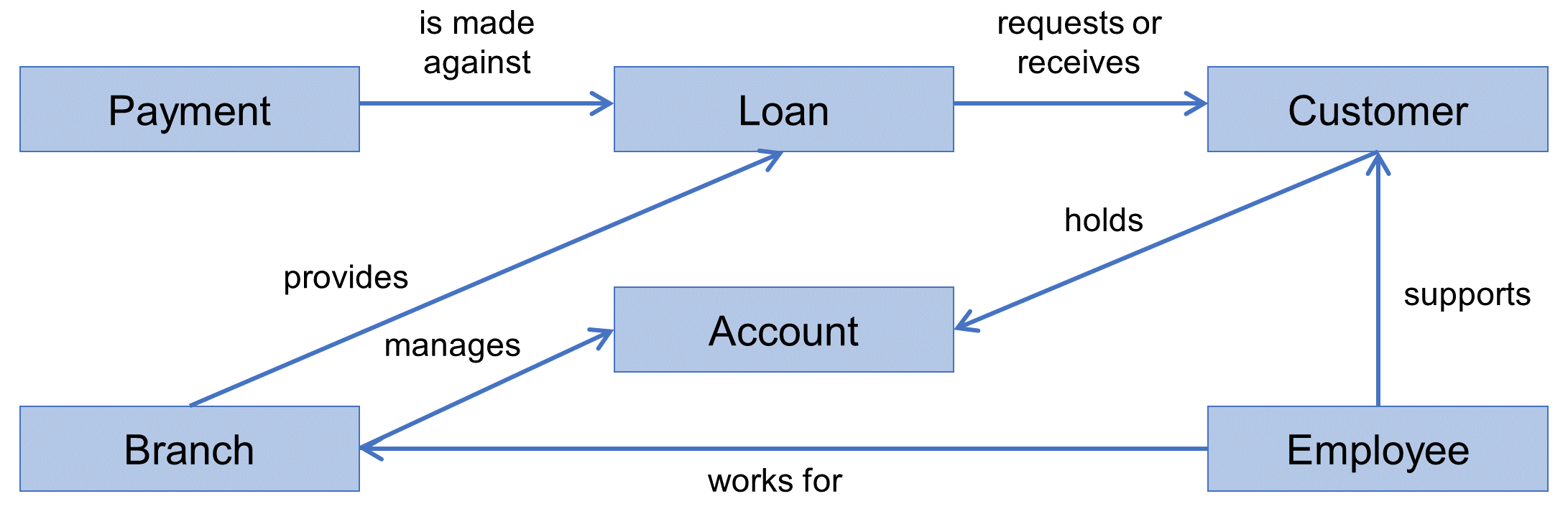

An information map is a collection of information concepts and their relationships to one another.

Mapping information in Business Architecture starts with listing those elements that matter most to the business as well as how they are described in business terms. A useful way to discern an information concept is to listen for the nouns that are used when talking about the business. Every noun is potentially an information concept. By using a noun-challenge process, it is possible to determine if the noun represents an item of information that the business cares about. In other words, does anyone in the business need to know, store, or manipulate the thing that the noun represents?

A simple, high-level example of an information map is shown in Figure 5. This shows some key information concepts and inter-relationships that might be found at a financial company.

Information maps can also be formally modeled; for example, as ArchiMate models, Unified Modeling Language™ (UML®) class diagrams, and Entity Relationship Diagrams (ERDs).

Information maps can be mapped to business capabilities, value streams, as well as organization maps. For more details, see the TOGAF Series Guide: Information Mapping ![]() .

.

Organization Mapping

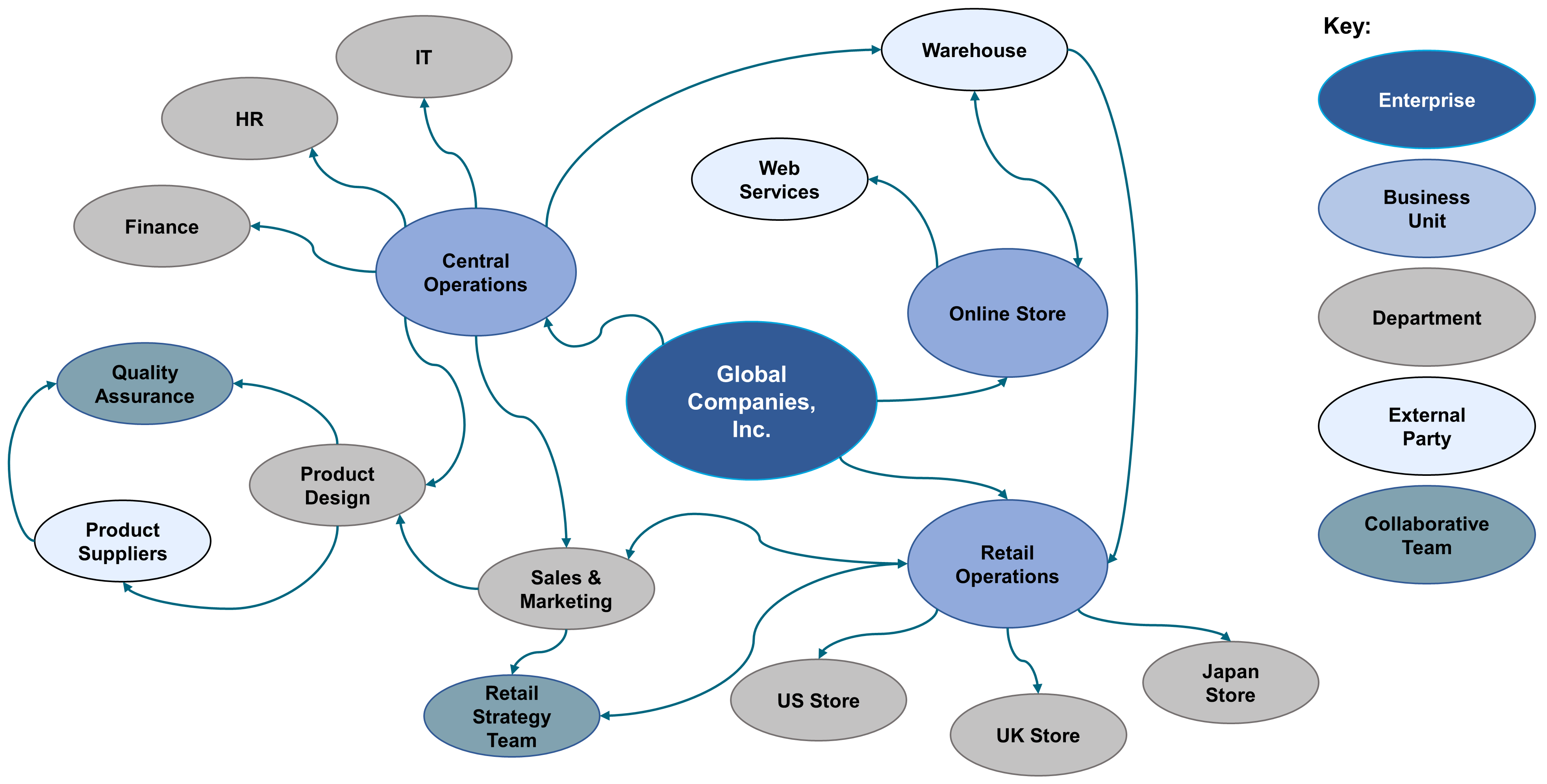

An organization map is a Business Architecture blueprint that shows:

-

The main organizational units, partners, and stakeholder groups that comprise the ecosystem of an enterprise.

-

The working relationships (informal as well as formal) between each of those entities.

These two primary characteristics reflect what distinguishes organization maps from traditional organization charts, which are more likely to portray the reporting lines that exist between named individuals who are in charge of each department. Instead of describing the business in terms of a top-down hierarchy that is focused on people and titles, an organization map depicts it in more fluid terms – as a network of relationships and interactions between business entities that may extend beyond the legal boundaries of the enterprise.

The benefits of organization mapping include:

-

Improves understanding of the organization

-

Improves strategic planning

-

Provides organizational context for deployment

-

Improves communication and collaboration

-

Improves the effectiveness of organizational change management

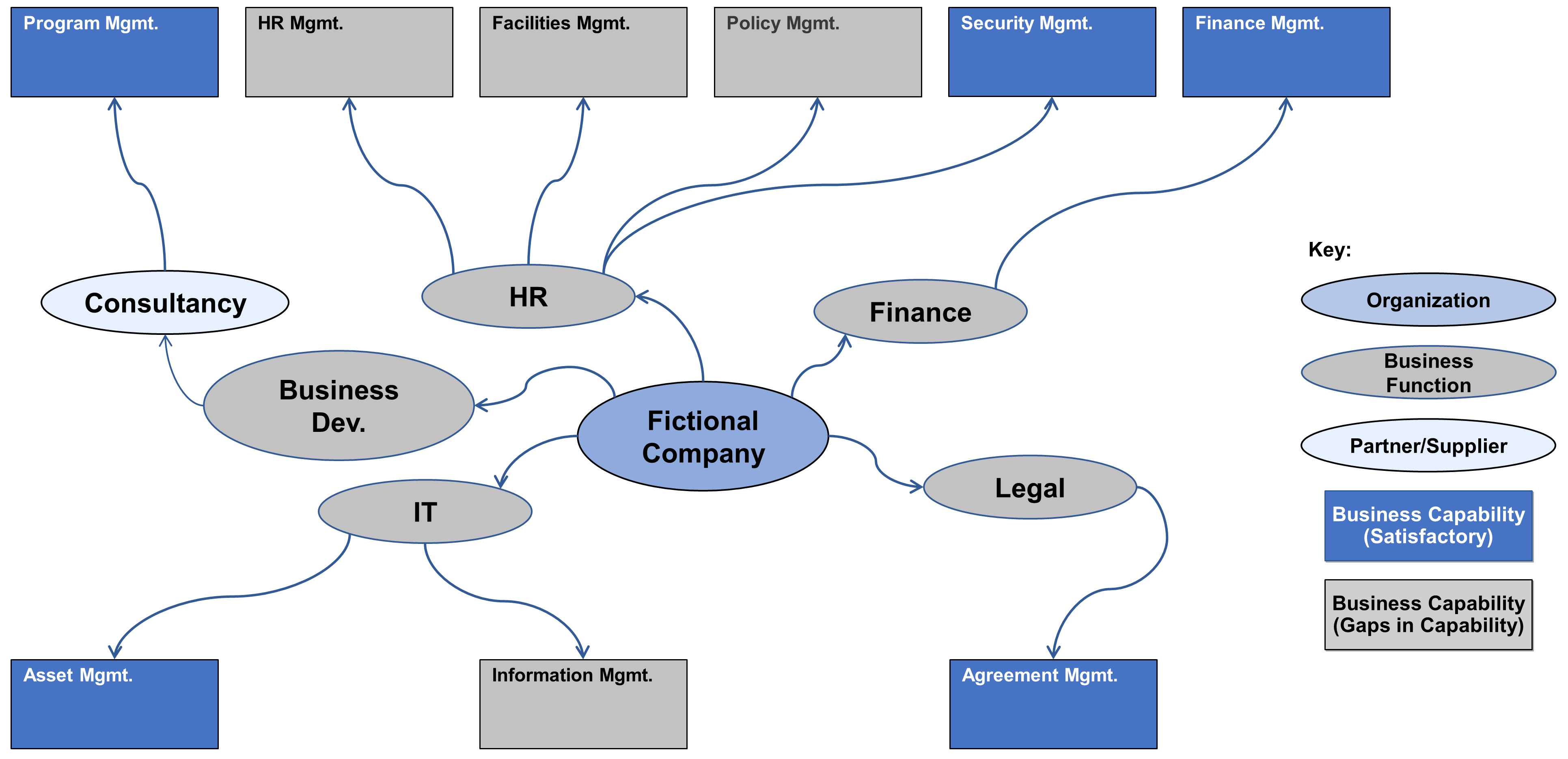

Organization maps, as shown in Figure 6, depict internal and external relationships as well as the collaborations from across the enterprise and beyond to include its ecosystem of business partners and stakeholders. The central oval (the enterprise) should be interpreted as denoting the total scope to be represented in the map, not just as the name of the legal entity. Also note that all of these entities are organization units, while the term business unit is being used to denote the next level below the enterprise (in this case representing business functions).

An organization map can be extended, as shown in Figure 7, to show the relationships between organization units and other Business Architecture domains such as business capabilities.

Business Scenarios

The Business Scenario method is used as a technique to help identify and understand the business requirements that an architecture must address. A good business scenario represents a significant business need or problem and enables vendors to understand the value of a solution to the customer.

A business scenario describes:

-

A business process, application, or set of applications

-

The business and technology environment

-

The people and computing components (“actors”) who execute the scenario

-

The desired outcome of proper execution

The method can be used in any ADM phase. Most notably it can be used in the Preliminary Phase to define requirements for establishing an Enterprise Architecture Capability, the initial phase of an ADM cycle, Phase A (where it is used to define relevant business requirements and to build consensus with stakeholders), as well as in the Business Architecture phase, to derive the characteristics of the architecture directly from the high-level requirements of the business. The technique may be used iteratively, at different levels of detail in the hierarchical decomposition of the Business Architecture.

The method is a follows:

-

Identify, document, and rank the problem that is driving the scenario

-

Document, as high-level architecture models, the business and technical environments where the problem situation is occurring

-

Identify and document desired objectives; the results of handling the problems successfully (ensure the objectives are SMART)

-

Identify human actors (participants) and their place in the business model

-

Identify computer actors (computing elements) and their place in the technology model

-

Check for fitness-for-purpose, and refine only if necessary

Data/Information Architecture

Documentation

| Document | Summary |

|---|---|

TOGAF Series Guide: Information Architecture: Business Intelligence & Analytics |

This document describes information architecture techniques to support architecture work using Business Intelligence (BI) and Analytics. This document includes reference models for the assessment and design of BI & Analytics capabilities, and an adaptation of the TOGAF ADM to support the BI & Analytics capability. |

TOGAF Series Guide: Information Architecture: Customer Master Data Management (C-MDM) |

This document describes an approach for implementing Customer Master Data Management (C-MDM) in an organization. It includes people, process, organizations, and systems to manage customer master data as an asset. |

TOGAF Series Guide: Information Architecture: Metadata Management |

This document describes best practices for Metadata Management, including a framework for accelerating the delivery of value from data, and a common language for describing the Metadata Management capability. It also emphasizes the benefits of data documentation, and the necessary efforts required to set up an effective Metadata Management capability within an organization. |

Customer Master Data Management (C-MDM)

The purpose of C‑MDM in an organization is to increase the value of customer information shared across the organization. It is a data foundation for most organizations.

The TOGAF Series Guide: Information Architecture: Customer Master Data Management (C-MDM) ![]() , Chapter 4, describes an adaptation of the TOGAF ADM to support the execution of a C-MDM transformation program.

, Chapter 4, describes an adaptation of the TOGAF ADM to support the execution of a C-MDM transformation program.

Agile Methods

Documentation

| Document | Summary |

|---|---|

TOGAF Series Guide: Enabling Enterprise Agility |

This document describes in general terms how the TOGAF Standard can be adapted to support an “Agile enterprise”. It is written to be applicable to any Agile delivery method that follows the commonly accepted Agile approach of iterative development through a series of sprints. |

TOGAF Series Guide: Applying the TOGAF ADM using Agile Sprints |

This document describes how sprints can be applied in a number of scenarios: — Collaboratively applying Enterprise Architecture and the TOGAF ADM following an Agile approach — Creating an Enterprise Architecture tuned for use together with Agile practices — Supporting and collaborating with Agile teams for a given business need — Enabling Enterprise Architects to leverage an Agile practice to assure that the Agile delivery of a solution is in alignment with strategic objectives |

What is Meant by Agility and Why is it Important?

Enterprise agility is a commonly used term but the exact definition differs among practitioners. The most common characteristics include:

-

Responsiveness to change: a flexible approach that anticipates and explicitly plans for change, typically involving short iterations and the frequent re-prioritization of activities

-

Value-driven: activity is driven by delivering value; priorities are continually re-assessed to deliver high-value items first and work on intermediate products and documentation is minimized

-

Practical experimentation: a preference for trying things out and learning from experience as opposed to extensive theoretical analysis, sometimes characterized as “fail fast”

-

Empowered, autonomous teams: skilled, multi-disciplinary teams work closely together, taking responsibility for their own decisions and outputs

-

Customer communication and collaboration: working closely with the customer and adapting to their needs; valuing collaboration and feedback over formalized documentation and contracts

-

Continuous improvement: the internal drive to improve the way an organization performs

-

Respect for people: people are put first, above process and tools – they are treated with respect; flexibility, knowledge transfer, and personal development are high priorities

Agility is important because it enables an enterprise to better react to change by being more customer and product-centric, more efficient, and better able to ensure regulatory compliance

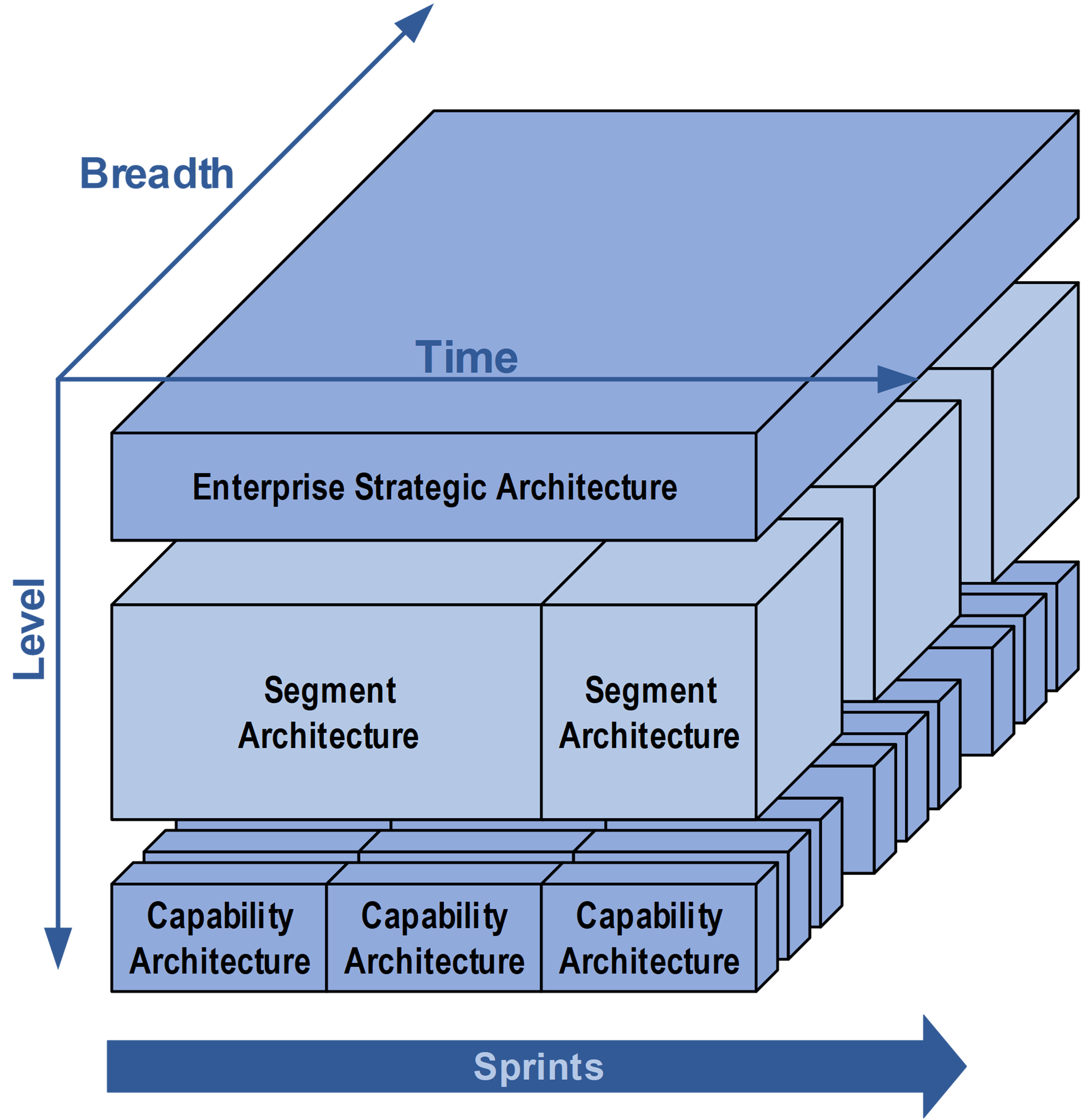

Different Levels of Detail Enable Agility

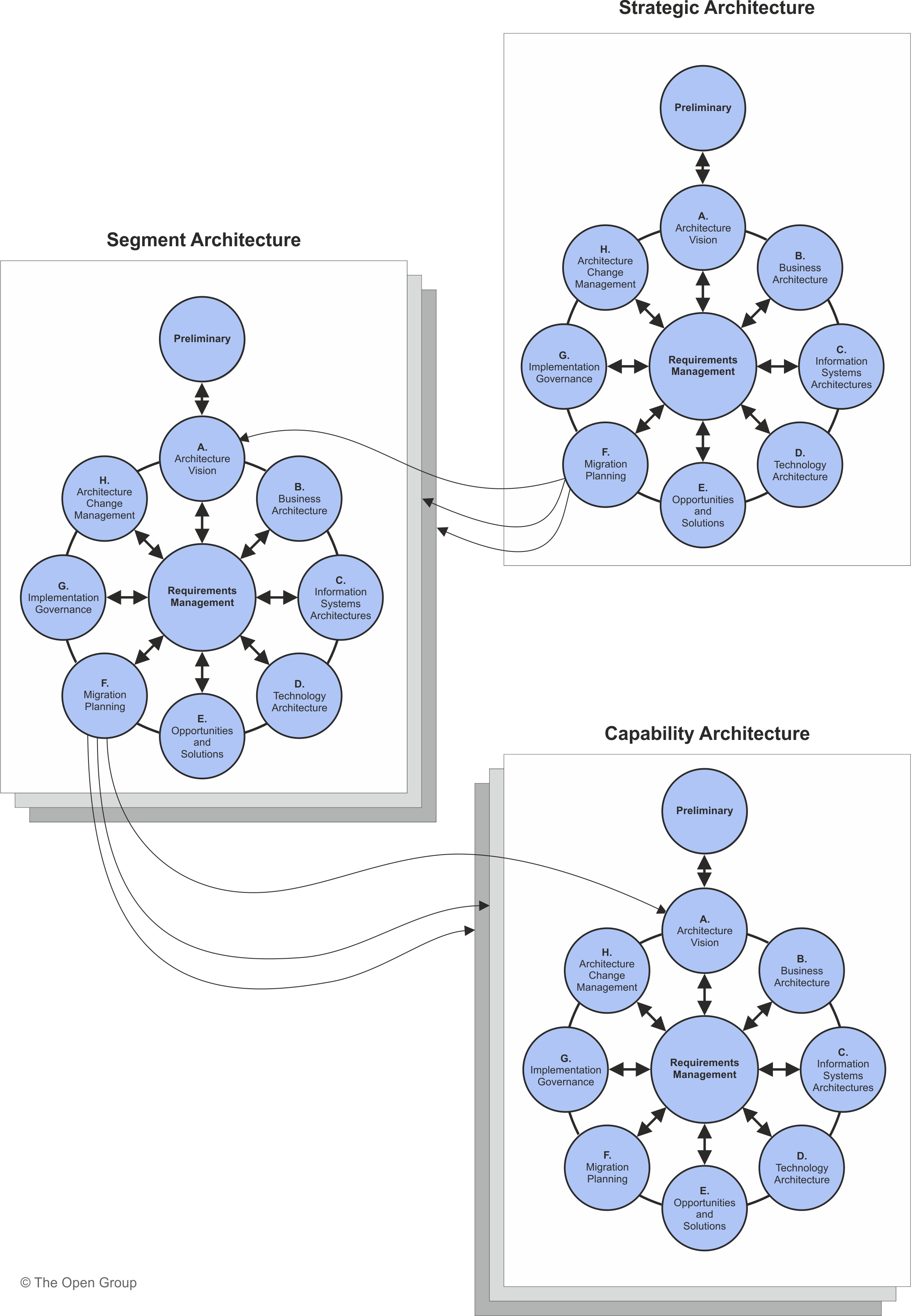

The TOGAF framework presents a model identifying three levels of detail that can be used for partitioning architecture development:

-

Enterprise Strategic Architecture

-

Segment Architecture

-

Capability Architecture

These levels are illustrated in Figure 8.

Top-down, the Enterprise Strategic Architecture provides a high-level view of the area of the enterprise impacted by change. It enables an understanding of the overall strategic direction of the enterprise at a high level, and must be sufficiently broad to establish the context within which the segments and capabilities fit. It is necessary to plan and design the entire endeavor, and to avoid unanticipated consequences.

The middle layer, the Segment Architectures, typically provide direction at the portfolio, program, or product level. These large-scale segments are often aligned to natural boundaries of functionality.

The bottom layer, the Capability Architectures, are detailed descriptions of (increments of) business capabilities. These may align to delivery sprints, or multiple sprints may be needed to deliver a capability. They are sufficiently detailed to be handed to developers for action. Sprints may occur at any level, but are most commonly associated with the delivery of capabilities or increments of capability. Sprints can occur in parallel.

Two major factors to achieving successful agility at an enterprise level are:

-

Managing the scope, understanding when a new capability is needed, how much of the enterprise is impacted, and how different parts of the enterprise interact.

-

Having a sufficient understanding of the overall strategic direction of the enterprise, key business capabilities, and the relationships between them in order to minimize the risks of unanticipated consequences and piecemeal development, and identify any change which would detract from the overall strategy for the enterprise. This understanding facilitates an impact assessment of any proposed change.

An Approach to Structuring Agile Enterprise Architecture

An approach to applying Agile Enterprise Architecture is through a hierarchy of ADM cycles, as illustrated in Figure 9.

The activities around defining Segment Architectures can start as soon as the relevant areas have been identified in the Strategic Architecture. Even if not all of these segments have been defined, architecture work can start in those already identified. In a similar way, work on defining Capability Architectures need not wait until all Segment Architectures have been defined. Work on different segments and capabilities may proceed in parallel.

Experience gained when developing a Capability Architecture should influence the higher-level Segment Architecture. Experience gained when developing a Segment Architecture should influence the higher-level Strategic Architecture.

Agile Delivery teams should collaborate closely with architects to ensure that the Sprint teams understand and comply with architecture specifications (which may be expressed as guardrails or runways), and to enable rapid feedback to future architecture iterations.

It is important to keep in mind the big picture to ensure Implementation teams remain aligned to the overall strategy. Therefore, a balance must be made between providing sufficient detail at each level, to give clarity and maintain alignment, versus “Big Design Up Front” (BDUF), which results in exploring too much detail too soon without the benefit of feedback from delivery sprints. This is often referred to as the Minimum Viable Architecture (MVA).

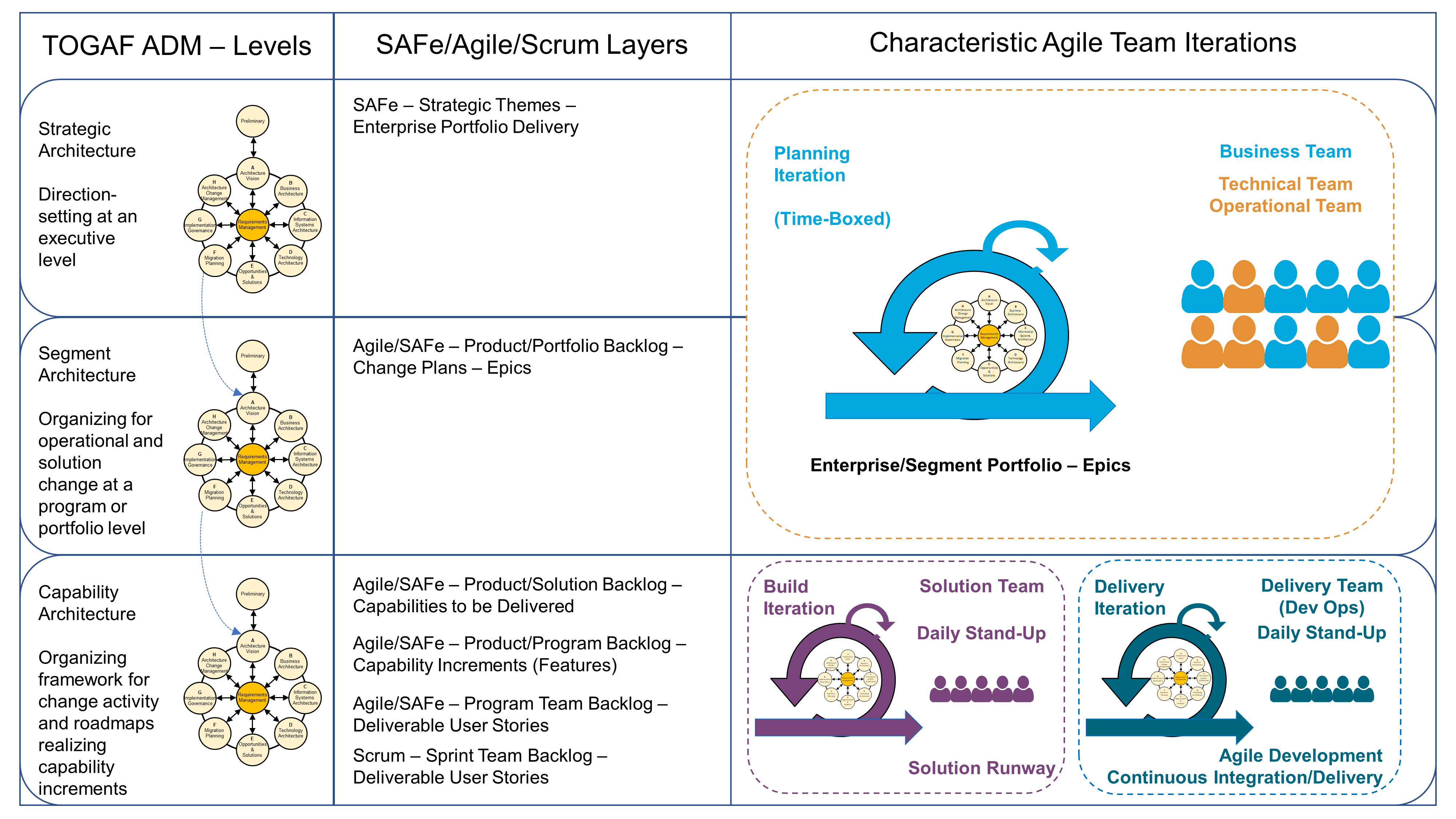

Mapping to Agile Concepts

The hierarchy of ADM processes approach can also be applied using techniques such as SAFe® and Scrum. Agile techniques consider that development and delivery work can progress based on one integrated team across all levels (business, technical, solution, build, and delivery) working in single connected sprints or across the types of boundaries. This is illustrated in Figure 10.

Agile Product Management

Agile Architecture requires a much closer focus on the outcomes, involving a shift from a project to a product-centric approach. While most Agile efforts take place in the solution space, techniques that address the problem space, such as design thinking[1] and business model canvassing, help to shape the architecture direction to achieve the solution. Requirements often come on a just-in-time basis, requiring iterative evaluation to reaffirm the problem definition (TOGAF ADM Phase A) and the architecture approach to arrive at the desired solution (TOGAF ADM Phases B, C, and D).

This produces an holistic architecture approach with less individual focus on the common domains of architecture and more emphasis on collaborative views across all domains focused around the required product.

An important concept for Agile Architecture is intentional architecture, which specifies a set of purposeful, planned architectural strategies and initiatives to enhance solution design, performance, and usability as well as providing guidance for inter-team design and implementation synchronization.

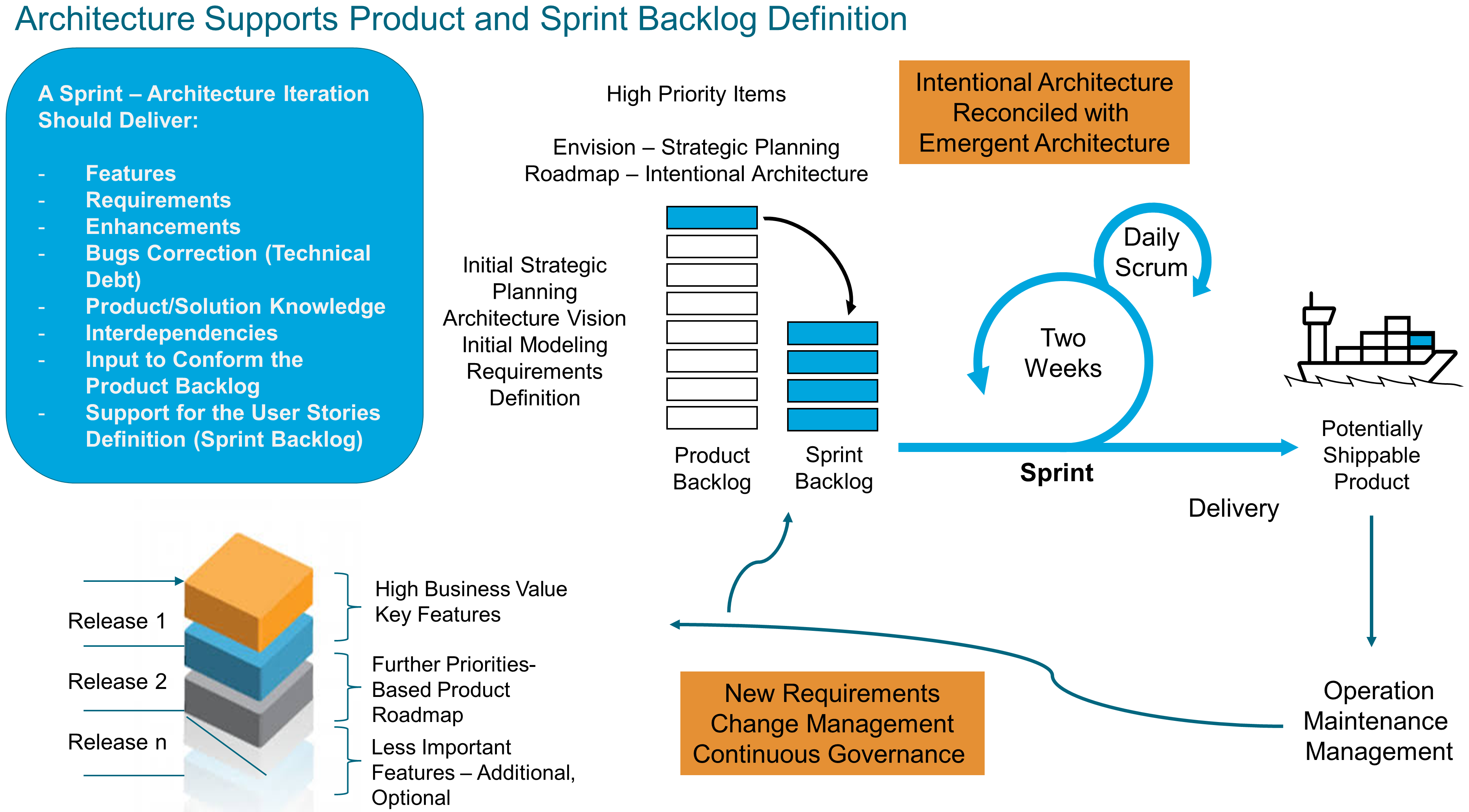

In Figure 11, intentional architecture is delivered as part of the Capability Architecture specification, and it is aimed to provide guardrails to support implementation. The output of the Strategic Architecture gives input to define the product backlog that is defined in further detail in the Segment Architecture. At the Capability Architecture level, the sprint backlog is defined and also the intentional architecture that will guide implementation (deploy target). Change management will address any new requirements and will support the refinement and prioritization for the product backlog.

How to Sprint with the TOGAF ADM

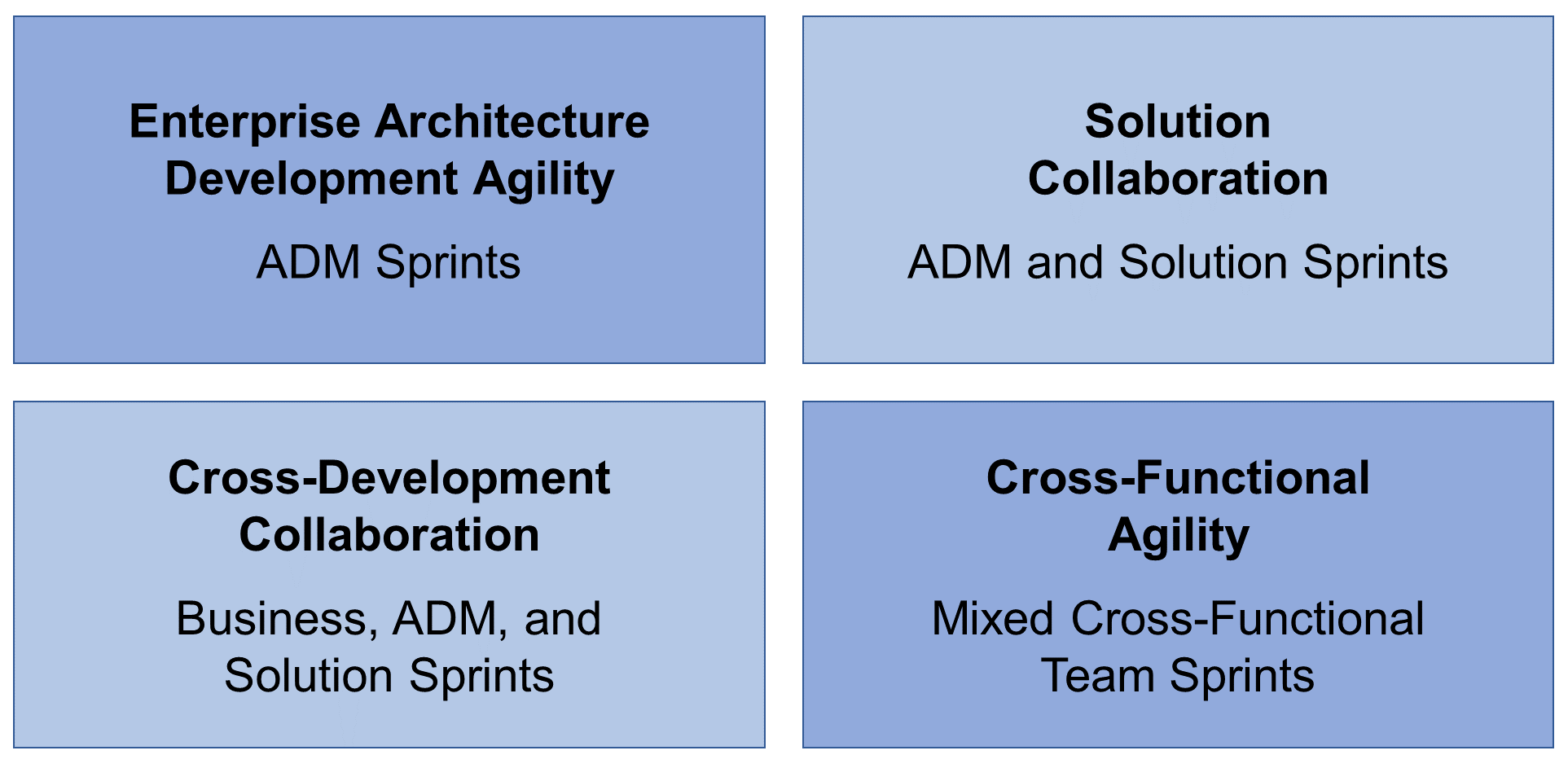

There are a number of ways to use sprints in Enterprise Architecture development. This section briefly explains four different Agile Enterprise Architecture approaches, as shown in Figure 12. The choice of which to apply depends on the needs of the Agile practice in the organization.

The four ways of collaboration are described in Table 12.

| Collaboration Approach | Summary |

|---|---|

Enterprise Architecture Development Agility |

Deliver the Enterprise Architecture for the business change using sprints. The necessary ADM phases (A to F) to deliver the Enterprise Architecture are divided into a set of sprints, often with a slice (partition) of the ADM (A to F) in each sprint. Governance will be applied following the TOGAF governance framework that may also be adapted to be applied in an Agile way. |

Solution Collaboration |

Deliver the solution(s) with collaborating Enterprise Architecture and Agile Solution team sprints. Each sprint contains both Enterprise Architecture and Agile solution development. The Enterprise Architecture team will create MVAs for subsequent development sprints. |

Cross-Development Collaboration |

Deliver the solutions with collaborating Agile business development, Agile Enterprise Architecture, and Agile solution development sprints. Each sprint contains Agile business development, Agile Enterprise Architecture, and Agile solution development. The Business Development team will create Minimum Viable Business Developments (MVBDs) for subsequent Enterprise Architecture sprints, and the Enterprise Architecture team will create MVAs for subsequent development sprints. Delivering Enterprise Architecture has contexts and within each context the interpretation of the sprint, outcome, and membership will vary. |

Cross-Functional Agility |

Deliver the solution with mixed, cross-functional Sprint teams all containing Agile business development, Agile Enterprise Architecture, and Agile solution development competencies. Each Sprint team contains business development, Enterprise Architecture, and Agile solution development competencies to break silos and ensure consistent innovation. These competencies are collaborating in the same team. |

For more detail see the TOGAF Series Guide: Applying the TOGAF ADM using Agile Sprints ![]() .

.

TOGAF Standard Reference Models and Method

Documentation

| Document | Summary |

|---|---|

TOGAF Series Guide: TOGAF Digital Business Reference Model (DBRM) |

This document provides an industry-independent outline of common core components that are essential building blocks for the modern digital enterprise. It enables organizations to develop an appropriate digital architecture blueprint in response to their changing strategies, business model, operating model, and operations. |

TOGAF Series Guide: Government Reference Model |

This document provides a standard reference model template that can be used to describe any business in the public sector and allow for different architecture approaches and analysis techniques. It gives public sector organizations a common way to view themselves in order to plan and execute effective transformational change. |

TOGAF Series Guide: Architecture Maturity Models |

This document introduces the concept of Architecture Capability Maturity Models; techniques for evaluating and quantifying an organization’s maturity in Enterprise Architecture, including a publicly available framework as an example, which can be used by any enterprise to develop their own organization-specific maturity model. |

TOGAF Series Guide: Architecture Project Management |

This document provides guidelines for TOGAF architects on how to manage an Architecture Project using an approach that supplements the TOGAF ADM with selected project management techniques. The goal of this approach is to enhance an Architecture Project’s chances of success through better planning, monitoring, and communication. |

TOGAF Series Guide: Architecture Skills Framework |

This document provides a set of role, skill, and experience norms for staff undertaking Enterprise Architecture work. It provides a view of the competency levels for specific roles within the Enterprise Architecture team, defining specific roles, the skills required by those roles, and the depth of knowledge required to fulfill each role successfully. |

Digital Business Reference Model (DBRM)

The Digital Business Reference Model (DBRM) presents a generic reference model that may be adapted and used by organizations to enable sustainable enterprise design, organizational agility, and interoperability in response to the evolving customer needs and the business ecosystem.

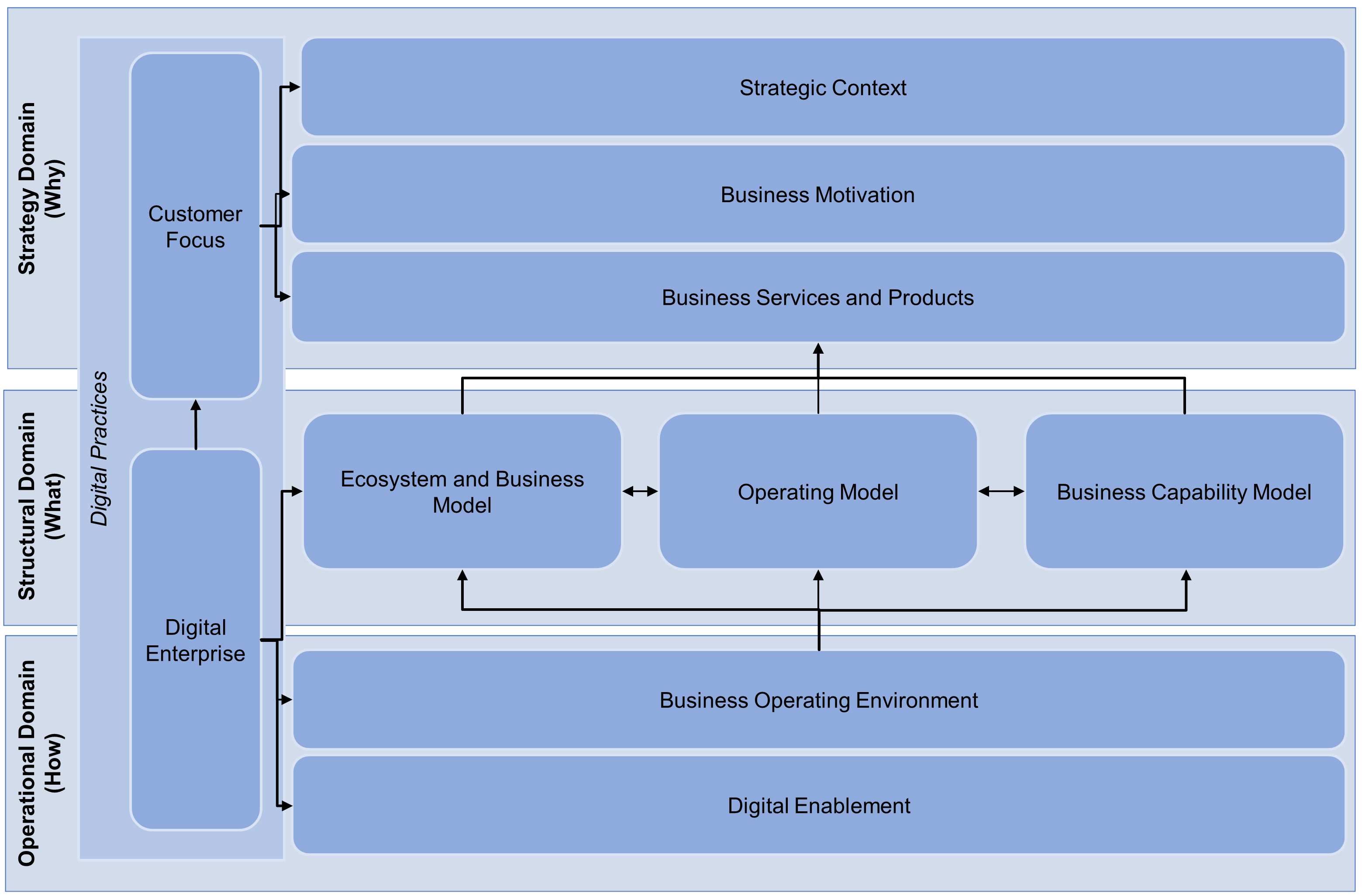

The high-level view of the DBRM is depicted in Figure 13.

The DBRM provides guidance on the adoption of relevant aspects of The Open Group TOGAF Standard and other related standards, particularly The Open Group DPBoK and Open Agile Architecture standards.

The DBRM consists of ten core elements categorized into four domains as follows:

-

Digital Domain:

-

Customer Focus

-

Digital Enterprise

-

-

Strategy Domain:

-

Strategic Context

-

Business Motivation

-

Business Services and Products

-

-

Structural Domain:

-

Ecosystem and Business Model

-

Operating Model

-

Business Capability Model

-

-

Operational Domain:

-

Business Operating Environment

-

Digital Enablement

-

The four domains – Digital, Strategic, Structural, and Operational – enable the DBRM to address specific stakeholder concerns and enable consistent stakeholder management.

The Digital Domain is essential to enable an outside-in approach for the creation and management of Digital Products and Services with an increasing digital component or to lead the organization through the digital journey towards a digital business.

The Strategy Domain is addressed by the Strategic Context, Business Motivation, and Business Services and Products elements, which are about determining the “why” of the business.

Underpinning the core Business Services and Products element are the elements of the DBRM that focus on the “what” of the business – the Ecosystem and Business Model, Operating Model, and Business Capability Model are inter-related. They collectively define the means with which the business will establish and deliver the identified core business services to achieve the intended business objectives as defined in the Business Motivation element. They address the Structural Domain of the DBRM.

The Operational Domain is addressed by the Business Operating Environment and Digital Enablement elements – the “how” of the business. They enable the business to deliberately determine the requirements and implications of the Business Operating Environment in response to the intended business strategy.

Government Reference Model

The Government Reference Model (GRM) gives public sector organizations a common way to view themselves in order to plan and execute effective transformational change. It provides a standard reference model template that can be used to describe any business in the public sector and allow for different architecture approaches and analysis techniques. The intended audience of the GRM includes decision-makers and designers of change in the public sector.

Table 14 shows the names and description of various types of sectors that are in the GRM.

| Sector | Definition |

|---|---|

International Affairs and Trade |

Activities undertaken by the government to facilitate financial support and trade with international economies, and related to the conduct and implementation of policies, aid programs, treaties, and diplomatic relations. |

Defense and Security |

Corresponds to the research, maintenance, equipment, procurement, and development of forces, weapons, and related entities. This also comprises remuneration and benefits paid to all active and non-active civilians and personnel. |

General Government (Customer Service, Customer Operations) and Local Services |

The provision of general customer services and operations including registrations, licensing, applications, workforce planning, social services, management of labor rights, and local services. |

Young People and Education |

Educational programs that correspond to early years, primary school, secondary school, higher education, and specialist schooling; children’s social services, safeguarding, and associated children and adolescent services; and skill or training activities undertaken by the government to promote education. |

Health and Community Wellbeing |

Encompasses medical and nursing governance, strategy and care services provided to individuals and families, research, and the provision of hospital and community services to safeguard mental and physical health. |

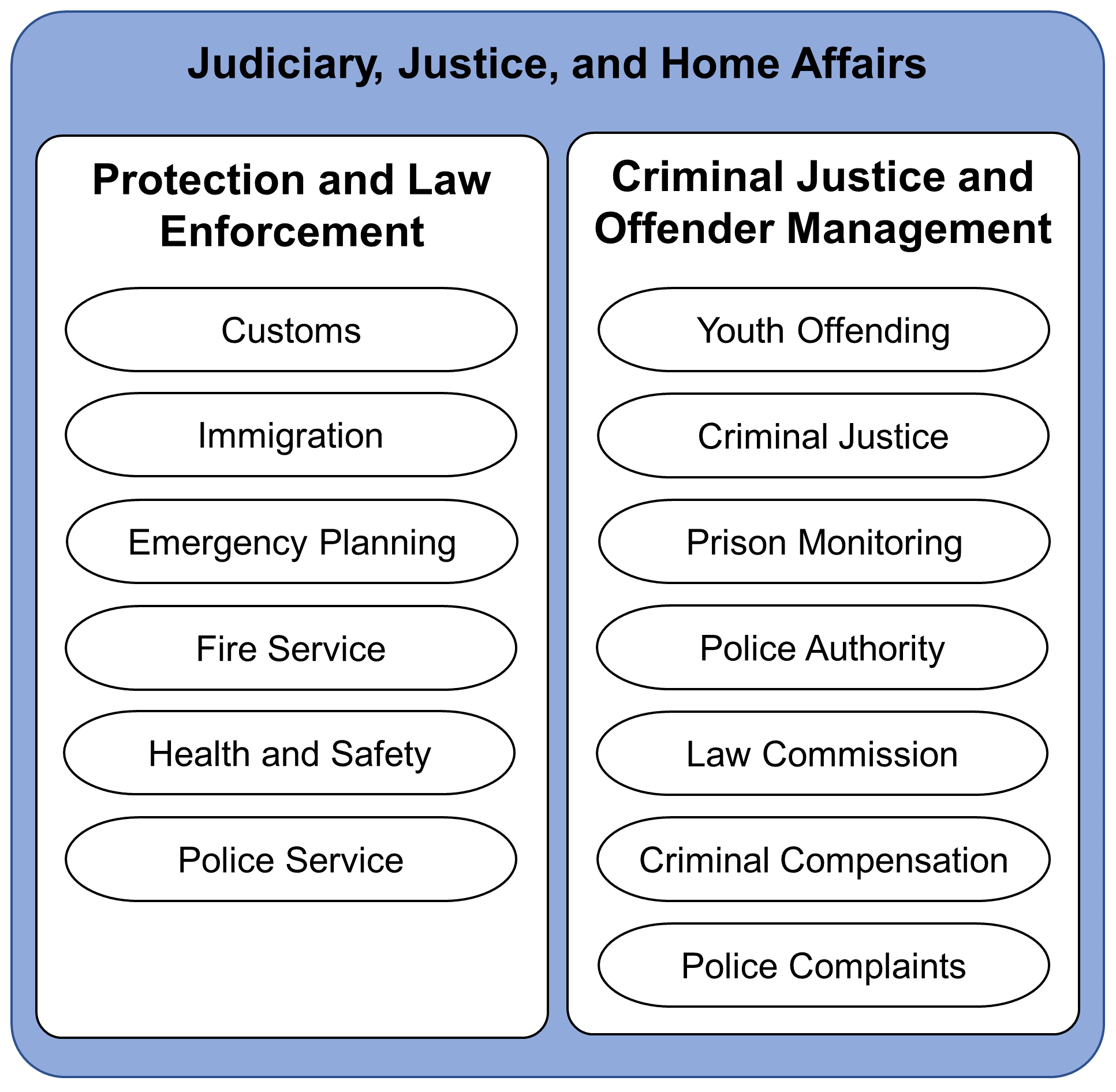

Judiciary, Justice, and Home Affairs |

Covers the total cost of judiciary, prosecution, expenses connected with funding protection, law enforcement services, and the cost of criminal justice including the incarceration, supervision, parole, and rehabilitation of prisoners. |

Financial |

Maintains controls over public spending, revenue, financial reporting, auditing, and providing the direction for future investment decisions and financial planning. |

Growth, Housing, and Environment |

Activities that ensure natural and urban environment responsibility, provision of core infrastructure, and protection of citizens’ standards of living and safety through the licensing and enforcement of regulation. |

Policy, Performance, Population, and Innovation |

Involves the development of policy across the government, the provision of statistics for population and performance against benchmarks to ensure continuous improvement, and incorporates strategic and long-term planning to identify future risks, opportunities, and solutions. |

Shared Services |

Co-ordinates and manages people, communications, finance, and transformation services on behalf of the public in order to facilitate the transfer of information and oversight of people, processes, and technology to support procurement and align to corporate strategy. |

Transport and Operations |

Activities that enable general operations and guarantee the safe transfer and availability of people and goods over land, air, sea, and space. |

The reference model provides a taxonomy for each service provisioned by the government and a common language that simplifies complex information components, enables consistency of cross-government services and common capabilities, and delivers a consistent view of commonly required operational services.

An example extract from the model is shown in Figure 14.

Architecture Maturity Models

Organizations that can manage change effectively are generally more successful than those that cannot. Many organizations know they need to improve their processes in order to successfully manage change, but do not know how. Such organizations typically either spend very little on process improvement (because they are unsure how to proceed), or spend a lot on a number of parallel and unfocused efforts, to little or no avail.

Architecture Maturity Models, more formally known as Capability Maturity Models (CMMs), address this problem by providing an effective and proven method for an organization to gradually gain control over and improve its change processes. Such models provide the following benefits:

-

They describe the practices that any organization must perform in order to improve its processes

-

They provide a yardstick against which to periodically measure improvement

-

They constitute a proven framework within which to manage the improvement efforts

-

They organize the various practices into levels, each level representing an increased ability to control and manage the development environment

An evaluation of the organization’s practices against the model – called an “assessment” – determines the level at which the organization currently stands. It indicates the organization’s ability to execute in the area concerned, and the practices on which the organization needs to focus in order to see the greatest improvement and the highest return on investment. The benefits of CMMs to effectively direct effort are well documented.

The TOGAF Series Guide: Architecture Maturity Models describes the US Department of Commerce Architecture Capability Maturity Model as an aid to conducting assessments.

Architecture Project Management

Architecture Projects are typically complex in nature. They need proper project management to stay on track and deliver on promise. The TOGAF Series Guide: Architecture Project Management ![]() provides Architecture Project teams with an overall view and detailed guidance on what processes, tools, and techniques of PRINCE2® or PMBOK® can be applied alongside the TOGAF ADM for project planning, monitoring, and control. It also provides a detailed mapping of the processes and deliverables of the TOGAF framework against PRINCE2 and PMBOK.

provides Architecture Project teams with an overall view and detailed guidance on what processes, tools, and techniques of PRINCE2® or PMBOK® can be applied alongside the TOGAF ADM for project planning, monitoring, and control. It also provides a detailed mapping of the processes and deliverables of the TOGAF framework against PRINCE2 and PMBOK.

Architecture Skills Framework

The Architecture Skills Framework provides a set of role, skill, and experience norms for staff undertaking Enterprise Architecture work.

“Enterprise Architecture” and “Enterprise Architect” are widely used but poorly defined terms. They are used to denote a variety of practices and skills applied in a wide variety of architecture domains. There is a need for better classification to enable a more implicit understanding of what type of architect/architecture is being described.

This lack of uniformity leads to difficulties for organizations seeking to recruit or assign/promote staff to fill positions in the architecture field. Because of the different usages of terms, there is often misunderstanding and miscommunication between those seeking to recruit for, and those seeking to fill, the various roles of the architect.

The TOGAF Architecture Skills Framework attempts to address this need by providing definitions of the architecting skills and proficiency levels required of personnel, internal or external, who are to perform the various architecting roles defined within the TOGAF framework.

Skill categories include:

-

Generic skills, typically comprising leadership, teamworking, inter-personal skills, etc.

-

Business skills and methods, typically comprising business cases, business processes, strategic planning, etc.

-

Enterprise Architecture skills, typically comprising modeling, building block design, applications and role design, systems integration, etc.

-

Program or Project Management skills, typically comprising managing business change, project management methods and tools, etc.

-

IT general knowledge skills, typically comprising brokering applications, asset management, migration planning, SLAs, etc.

-

Technical IT skills, typically comprising software engineering, security, data interchange, data management, etc.

-

Legal environment, typically comprising data protection laws, contract law, procurement law, fraud, etc.