9. Organization and culture

9.1. Introduction

In the last section, we introduced the AKF scaling cube, and we now start the second half of the book based on a related thought experiment. As your team-based company grew, you reached a crisis point in scaling your digital product. Your single team could no longer cope as one unit with the increasing complexity and operational demands. In AKF cube terms, you are scaling along the y-axis, the hardest but in some ways the most important dimension to know how to scale along.

You are going through a critical phase, the “team of teams” transition. You have increasingly specialized people delivering an increasingly complex product, or perhaps even several distinct products. Deep-skilled employees are great, but you’ve noticed they tend to lose the big picture. You are in constant discussions around the tension between functional depth versus product delivery. And when you go from one team to multiple, the topic of the organization must be formalized.

You often think about how your company should be structured. There is no shortage of opinions there either. From functional centers of excellence to cross-functional product teams, and from strictly hierarchical models to radical models like holacracy, there seems to be an infinite variety of choices.

A structure needs to be filled with the right people. How can you retain that startup feel you had previously, with things getting this big? You’ve always known intuitively that great hires are the basis for your company’s success, but now you need to think more systematically about hiring. Finally, the people you hire will create your company’s culture. Many of your employees and consultants emphasize the role of culture, but what do they mean? Is there such a thing as a “good” culture? How is one culture better than another?

Ultimately, as you move into leadership, you realize that your concern for organization and culture is all about creating the conditions for success. You can’t drive success as an individual any more; that is increasingly for others to do. All you can do is set the stage for their efforts, provide overall direction and vision, and let your teams do what they do best.

This chapter proceeds in a logical order, from operational organization forms, to populating them by hiring staff, to the hardest to change questions of culture.

9.1.1. Outline

-

IT organization versus product organization

-

Product and function

-

Defining the organization

-

Waterfall and functional organization

-

The continuum of organizational forms

-

From functions to components to shared services

-

-

IT human resource management

-

Basic concerns

-

Hiring

-

Allocation and tracking people’s time

-

Accountability and performance

-

-

Why culture matters

-

Motivation

-

Schneider and Westrum

-

Toyota Kata

-

9.1.2. Learning objectives

-

Identify and describe the factors driving an organization’s differentiation into a multiple-team structure

-

Identify and describe the organizational challenges and issues that result when a multiple-team structure is instituted

-

Distinguish between functional versus product organizations

-

Compare and contrast various organizational forms

-

Describe basic issues in digital hiring and human resource management

-

Identify and discuss various concepts and aspects of culture in digital organizations

9.2. IT versus product organization

In the early stages, you have to hire generalists who are both willing and able to take on dozens of tasks at once. Your developers will have to speak with potential customers; your accountants will have to give advice on product direction, and the natural salesman on your team will need to put the phone down a few hours a day and set up a new employee’s computer. This is the exciting, four-people-and-an-idea stage popularly associated with startups— but it doesn’t last very long…For a lot of your employees, growing out of this phase will be a welcome development: programmers don’t want to be in accounting meetings, and salespeople don’t want to sit in a dark, quiet room with the engineers. People have talents and skills they want to develop, and a healthy degree of specialization allows them to do that.

Scaling Up

Some of the most important factors that organizational structure can affect are communication, efficiency, standards, quality, and ownership.

and Fisher

So, you are getting bigger now, and are no longer one single team. As the quote from Matt Blumberg’s Scaling Up indicates, you are becoming more specialized. Even as a cohesive, single team you had specialized support services. You needed legal and accounting advice to get the startup going. When you started hiring people, you needed HR and payroll. You also are buying things and paying bills, so you need bookkeeping, and you’ve got sales people and marketing people, and you need to support your customers and collect money they have promised to pay. At some point, you need an internal person whose daily job is money (they’ll become the CFO someday).

How are you going to organize? More importantly, how are you going to think about organizing? This is a hard question. It’s important to get organization right, and the question never goes away. As you grow and split into teams, the overall sense of mission that you felt as a single team is at risk of fading. How can you keep your “eyes on the prize” when there are mulitple teams that all see the world slightly differently? It’s critical, as you start to explore various coordination mechanisms, to remember that the team remains the highest-value logical unit, and must be protected. As we discussed in Chapter 4, product value is created by co-located, cross-functional, highly collaborative teams.

In keeping with our emergence model, let’s assume you’ve been fairly ad hoc in your organizational structure up to now, doing your best to avoid specialization. Perhaps you’ve even been working as a collective. Nevertheless, you’ve needed a variety of skills to get this far in your journey: you are certainly not all Java programmers! A critical decision you will have to make: do you want a traditional “IT versus Business” structure or a product-based organization?

When I am in business meetings, I hear people talk about digital as a function or a role. It is not. Digital is a capability that needs to exist in every job. Twenty years ago, we broke e-commerce out into its own organization, and today e-commerce is just a part of the way we work. That’s where digital and IT are headed; IT will be no longer be a distinct function, it will just be the way we work. …

…we’ve moved to a flatter organizational model with “teams of teams” who are focused on outcomes. These are colocated groups of people who own a small, minimal viable product deliverable that they can produce in 90 days. The team focuses on one piece of work that they will own through its complete lifecycle…in [the “back office”] model, the CIO controls infrastructure, the network, storage, and makes the PCs run. The CIOs who choose to play that role will not be relevant for long… [122]

General Electric Chief Information Officer

There are two major models that digital professionals may encounter in their career:

-

The traditional centralized back-office “IT” organization

-

Digital technology as a component of market-facing product management

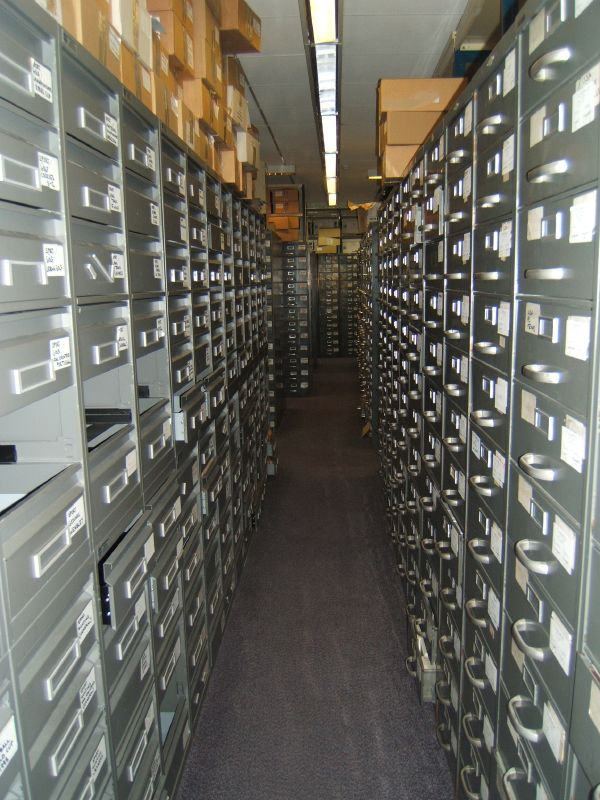

The traditional IT organization started decades ago, with “back-office” goals like replacing file clerks and filing cabinets (see Paper filing system [1]) with faster and more accurate computers. (We will go into further detail in Chapter 11). At that time, computers were not flexible or reliable, business did not move as fast, and there was a lot of value to be gained in relatively simple efforts like converting massive paper filing systems into digital systems. As these kinds of efforts grew and became critical operational dependencies for companies, the role of Chief Information Officer was created, to head up increasingly large organizations of application developers, infrastructure engineers, and operations staff.

The business objectives for such organizations centered on stability and efficiency. Replacing 300 file clerks with a system that didn’t work, or that wound up costing more was obviously not a good business outcome! On the other hand, it was generally accepted that designing and implementing these systems would take some time. They were complex, and many times the problem had never been solved before. New systems might take years -— including delays -— to come online, and while executives might be unhappy, oftentimes the competition wasn’t doing much better. CIOs were conditioned to be risk-averse; if systems were running, changing them was scrutinized with great care and rarely rushed.

The culture and practices of the modern IT organization became more established, and while it retained a reputation for being slow, expensive, and inflexible, no-one seemed to have any better ideas. It didn’t hurt that the end customer wasn’t interested in computers.

Then along came Apple, Microsoft, and the dot-com boom (see Amazon early version [2]). Suddenly everyone had personal computers at home and was on the Internet. Buying things! Computers continued to become more reliable and powerful as well. Companies realized that their back-office IT organizations were not able to move fast enough to keep up with the new e-commerce challenge, and in many cases organized their Internet team outside of the CIO’s control (which sometimes made the traditional IT organization very unhappy). Silicon Valley startups such as Google and Facebook in general did not even have a separate “CIO” organization, because for them (and this is a critical point) the digital systems were the product. Going to market against tough competitors (Alta Vista and Yahoo against Google, Friendster and MySpace against Facebook) wasn’t a question of maximizing efficiency. It was about product innovation and effectiveness and taking appropriate risks in the quest for these rapidly growing new markets.

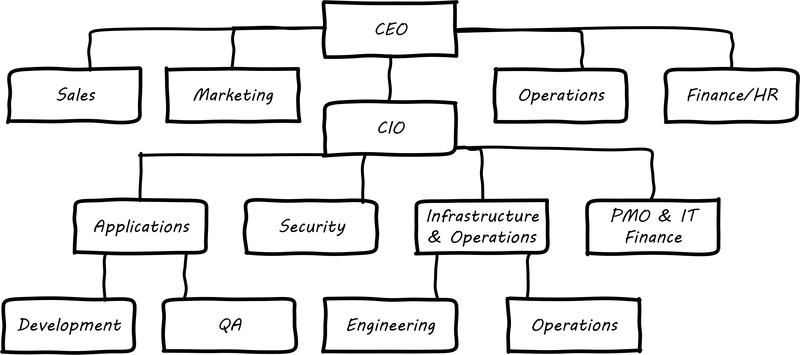

Let’s go back to our example of the traditional CIO organization. A typical structure under the CIO might look as shown in Classic IT organization.

(We had some related discussion in Chapter 6). Such a structure was perceived to be “efficient” because all the server engineers would be in one organization, while all the Java developers would be in another, and their utilization could be managed for efficiency. Overall, having all the “IT” people together was also considered efficient, and the general idea was that “the business” (Sales, Marketing, Operations, and back-office functions like Finance and HR) would define their "requirements" and the IT organization would deliver systems in response. It was believed that organizing into "centers of excellence” (sometimes called organizing by function) would make the practices of each center more and more effective, and therefore more valuable to the organization as a whole. However, the new digital organizations perceived that there was too much friction between the different functions on the organization chart. Skepticism also started to emerge that “centers of excellence” were living up to their promise. Instead, what was too often seen was the emergence of an “us versus them” mentality, as developers argued with the server and network engineers.

One of the first companies to try a completely different approach was Intuit. As Intuit started selling its products increasingly as services, it re-organized and assigned individual infrastructure contributors, e.g., storage engineers and database administrators, to the product teams with which they worked [2], p 103.

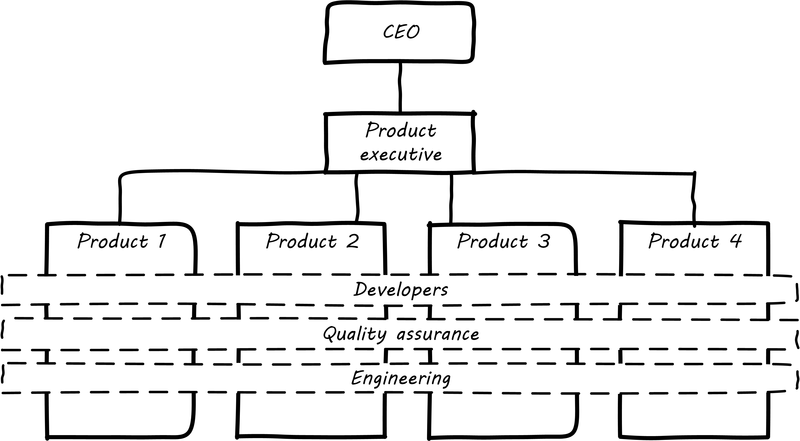

This model is also called the "Spotify model” (see New IT organization). The dotted line boxes (Developers, Quality Assurance, Engineering) are no longer dedicated “centers of excellence” with executives leading them. Instead, they are lighter-weight “communities of interest” organized into chapters and guilds. The cross-functional product teams are the primary way work is organized and understood, and the communities of interest play a supporting role. Henrik Kniberg provided one of the first descriptions of how Spotify organizes along product lines [159]. (Attentive readers will ask, “What happened to the PMO? and what about security?” There are various answers to these questions, which we will continue to explore in Part III).

The consequences of this transition in organizational style are still being felt and debated. Sriram Narayan, is in general an advocate of product organization. However, in his book Agile Organization Design, he points out that “IT work is labor-intensive and highly specialized,” and therefore managing IT talent is a particular organizational capability it may not make sense to distribute [195]. Furthermore, he observes that IT work is performed on medium to long time scales, and “IT culture” differs from “business culture,” concluding that "although a merger of business and IT is desirable, for the vast majority of big organizations it isn’t going to happen anytime soon."

Conversely, Abbott and Fisher in The Art of Scalability argue that "…The difference in mindset, organization, metrics, and approach between the IT and product models is vast. Corporate technology governance tends to significantly slow time to market for critical projects…IT mindsets are great for internal technology development, but disastrous for external product development” [2 pp. 122-124]. However, it is possible that Abbott and Fisher are overlooking the decline of traditional IT. Hybrid models exist, with “product” teams reporting up under “business” executives, and the CIO still controlling the delivery staff who may be co-located with those teams. We’ll discuss the alternative models in more detail below.

9.3. Defining the organization

There are many different ways we can apply these ideas of traditional functional organizing versus product-oriented organizing, and features versus components. How does one begin to decide these questions? As a digital professional in a scaling organization, you need to be able to lead these conversations. The cross-functional, diverse, collaborative team is a key unit of value in the digital enterprise, and its performance needs to be nurtured and protected.

Abbott and Fisher suggest the following criteria when considering organizational structures [2 p. 12]:

-

How easily can I add or remove people to/from this organization? Do I need to add them in groups, or can I add individual people?

-

Does the organizational structure help or hinder the development of metrics that will help measure productivity?

-

Does the organizational structure allow teams to own goals and feel empowered and capable of meeting them?

-

Which types of conflict will arise, and will that conflict help or hinder the mission of the organization?

-

How does this organizational structure help or hinder innovation within my company?

-

Does this organizational structure help or hinder the time to market for my products?

-

How does this organizational structure increase or decrease the cost per unit of value created?

-

Does work flow easily through the organization, or is it easily contained within a portion of the organization?

9.3.1. Team persistence

The traditional approach is that we have work and we bring “the right people” to the work. To be nimble -— to have organizational agility -— we have to have great teams of people and bring the work to the team [93].

Team persistence is a key question. The practice in project-centric organizations has been temporary teams, that are created and broken down on an annual or more frequent basis. People “rolled on” and “rolled off” of projects regularly in the common heavyweight project management model. Often, contention for resources resulted in fractional project allocation, as in “you are 50% on Project A and 25% on Project B” which could be challenging for individual contributors to manage. With team members constantly coming and going, developing a deep, collective understanding of the work was difficult. Hard problems benefit from team stability. Teams develop both a deeper rational understanding of the problem, as well as emotional assets such as psychological safety. Both are disrupted when even one person on a team changes. Persistent teams of committed individuals also (in theory) reduce destructive multi-tasking and context-switching.

9.4. Product and function

Even where they are not part of a value stream, activity-oriented teams tend to standardize their operations over time. Their appetite for offering custom solutions begins to diminish. Complaints begin to surface—“They threw the rule book at us,” “What bureaucracy!”

Agile IT Organization Design

When teams are aligned by services, are autonomous, and are cross-functionally composed, there is a significant decrease in affective conflict. When team members are alignment with shared goals and no longer need to argue about who is responsible or who should perform certain tasks, the team wins or loses together. Everyone on the team is responsible for ensuring the service provided meets the business goals.

and Fisher

By this time, you probably detect that there is a fundamental tension between functional specialization and end to end value delivery. The above two quotes reflect this tension — the tendency for specialist teams start to identify with their specialty and not the overall mission. The tension may go by different names:

-

Product versus function

-

Value stream versus activity

-

Process versus silo

As we saw previously, there are three major concepts used to achieve an end-to-end flow across functional specialties:

-

Product

-

Project

-

Process

These are not mutually exclusive models and may interact with each other in complex ways. (See the scaling discussion in the Part III introduction).

9.4.1. Waterfall and functional organization

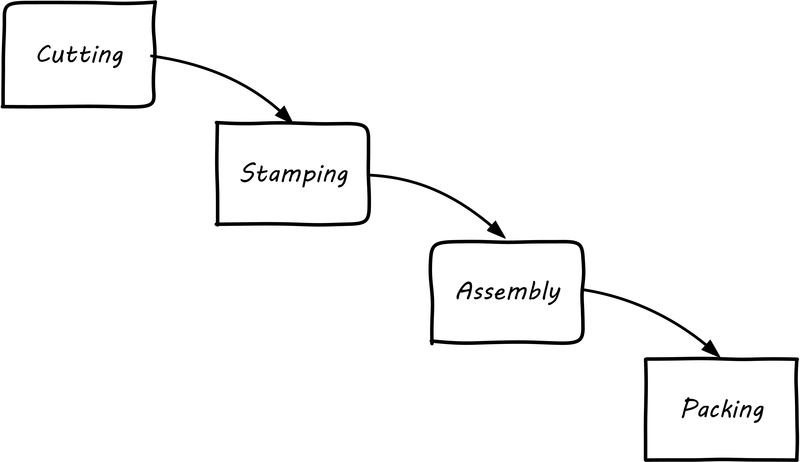

For example, some manufacturing can be represented as a very simple, sequential process model (see Simple sequential manufacturing).

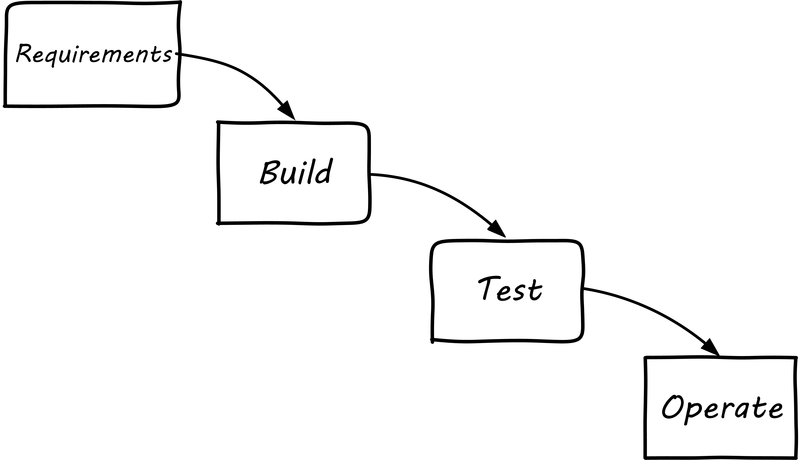

The product is already defined, and the need to generate information (i.e. through feedback) is at an absolute minimum. NOTE: Even in this simplest model, feedback is important. Much of the evolution of 20th century manufacturing has been in challenging this naive, open-loop model. (Remember our brief discussion of open-loop?) The original, open-loop waterfall model of IT systems implementation (see Waterfall) was arguably based on just such a naive concept.

(Review chapter 3 on waterfall development and Agile history). Functional, or practice, areas can continually increase their efficiency and economies of scale through deep specialization.

There are two primary disadvantages to the model of projects flowing in a waterfall sequence across functional areas:

-

It discourages closed-loop feedback

-

There is transactional friction at each handoff

Go back and review: the waterfall model falls into the “original sin” of IT management, confusing production with product development. As a repeatable production model, it may work, assuming that there is little or no information left to generate regarding the production process (an increasingly questionable assumption in and of itself). But when applied to product development, where the primary goal is the experiment-driven generation of information, the model is inappropriate and has led to innumerable failures. This includes software development, and even implementing purchased packages in complex environments.

9.4.2. The continuum of organizational forms

|

Note

|

The following discussion and accompanying set of diagrams is derived from Preston Smith and Don Reinertsen’s thought regarding this problem in Developing Products in Half the Time [254] and Managing the Design Factory [219]. Similar discussions are found in the Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge [214] and Abbott and Fisher’s The Art of Scalability [2]. |

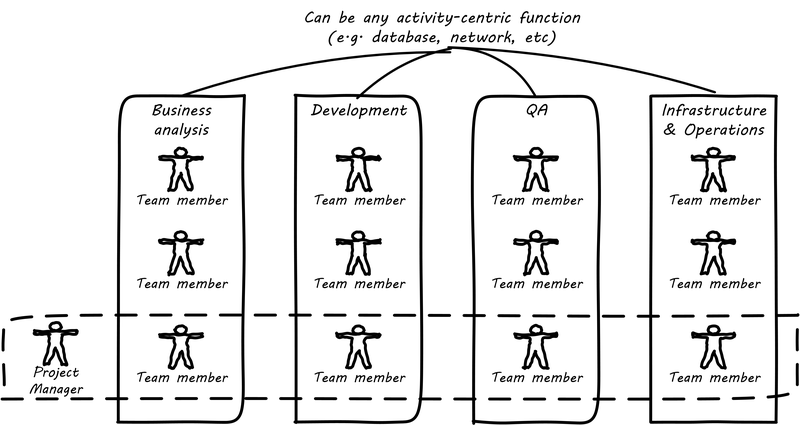

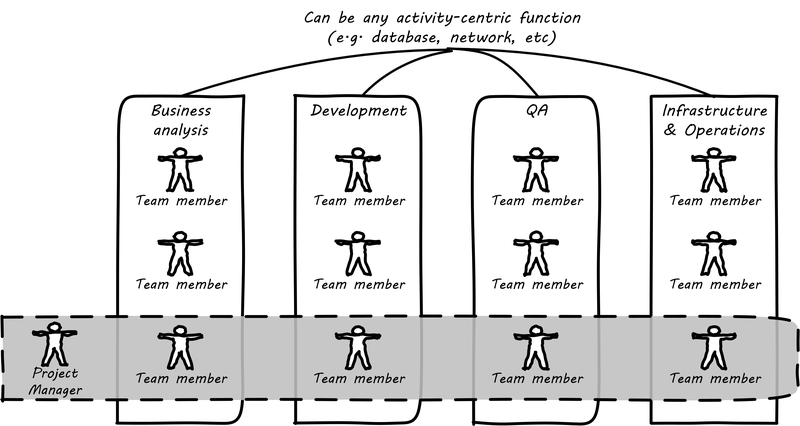

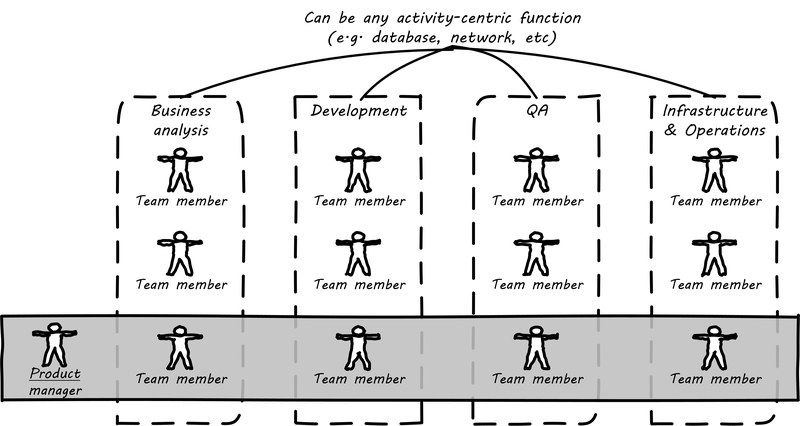

There is a spectrum of alternatives in structuring organizations for flow across functional concerns. First, a lightweight “matrix” project structure may be implemented, in which the project manager has limited power to influence the activity-based work, where people sit, etc. (see Lightweight project management across functions).

Work flows across the functions, perhaps called "centers of excellence,” and there may be contention for resources within each center. Often, simple “first in, first out” queuing approaches are used to manage the ticketed work , rather than more sophisticated approaches such as cost of delay. It is the above model that Reinertsen was thinking of when he said: “The danger in using specialists lies in their low involvement in individual projects and the multitude of tasks competing for their time.” Traditional infrastructure and operations organizations, when they implemented defined service catalogs, can be seen as attempting this model. (More on this in the discussion of ITIL and shared services.

Second, a heavyweight project structure may specify much more, including dedicated time assignment, modes of work, standards, and so forth (see Heavyweight project management across functions). The vertical functional manager may be little more than a resource manager, but does still have reporting authority over the team member and crucially still writes their annual performance evaluation (if the organization still uses those). This has been the most frequent operating model in the traditional CIO organization.

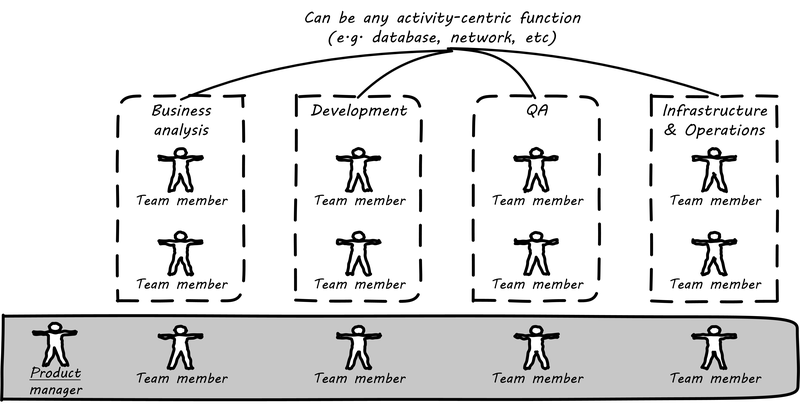

If even more focus is needed -— the now-minimized influence of the functional areas is still deemed too strong -— the organization may move to completely product-based reporting (see Product team, virtual functions). With this, the team member reports to the product owner. There may still be communities of interest (Spotify guilds and tribes are good examples) and there still may be standards for technical choices.

Finally, in the skunkworks model, all functional influence is deliberately blocked, as distracting or destructive to the product team’s success (see Skunkworks model).

The product team has complete autonomy and can move at great speed. It is also free to:

-

re-invent the wheel, developing new solutions to old and well-understood problems

-

bring in new components on a whim (regardless of whether they are truly necessary) adding to sourcing and long-term support complexity,

-

ignore safety and security standards, resulting in risk and expensive retrofits.

Early e-commerce sites were often set up as skunkworks to keep the interference of the traditional CIO to a minimum, and this was arguably necessary. However, ultimately, skunkworks is not scalable. Research by the Corporate Executive Board suggests that “Once more than about 15% of projects go through the fast [skunkworks] team, productivity starts to fall away dramatically.” It also causes issues with morale, as a two-tier organization starts to emerge with elite and non-elite segments [110].

Because of these issues, Don Reinertsen observes that “Companies that experiment with autonomous teams learn their lessons, and conclude that the disadvantages are significant. Then they try to combine the advantages of the functional form with those of the autonomous team” [219].

The Agile movement is an important correction to dominant IT management approaches employing open-loop delivery across centralized functional centers of excellence. However, the ultimate extreme of the skunkworks approach cannot be the basis for organization across the enterprise. While functionally specialized organizations have their challenges, they do promote understanding and common standards for technical areas. In a product-centric organization, communities of interest or practice provide an important counterbalancing platform for coordination strategies to maintain common understandings.

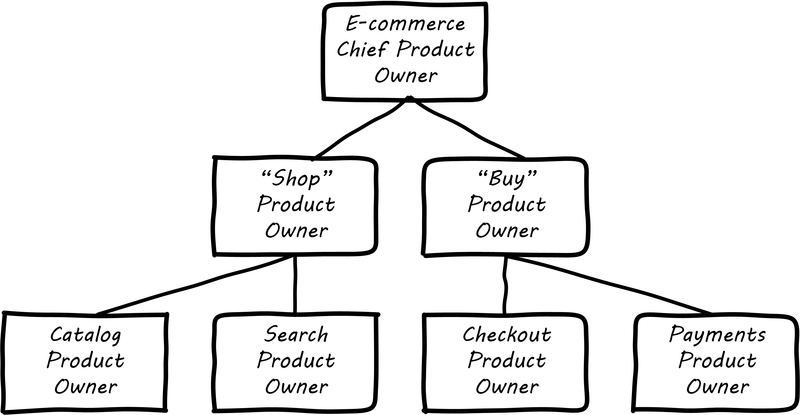

9.4.3. Scaling the product organization

The functional organization scales well. Just keep hiring more Java programmers, or DBAs, or security engineers and assign them to projects as needed. However, scaling product organizations requires more thought. The most advanced thinking in this area is found in the work of Scrum authors such as Ken Schwaber, Mike Cohn, Craig Larman and Roman Pichler. Scrum, as we have discussed, is a strict, prescriptive framework calling for self-managing teams with

-

Product owner

-

Scrum master

-

Team member

Let’s accept Scrum and the 2-pizza team as our organizing approach. A large scale Scrum effort is based on multiple small teams, e.g., representing AKF scaling cube partitions (see Product owner hierarchy footnote:[Similar to [210], p. 12; [238]). If we want to minimize multi-tasking and context-switching, we need to ask “how many product teams can a given product owner handle?” In Agile Product Management with Scrum, Roman Pichler says, “My experience suggests that a product owner usually cannot look after more than two teams in a sustainable manner” [210 p. 12]. Scrum authors, therefore, suggest that larger scale products be managed as aggregates of smaller teams. We’ll discuss how the product structure is defined in Chapter 8.

9.4.4. From functions to components to shared services

We have previously discussed feature _versus_component teams. As a reminder, features are functional aspects of software (things people find directly valuable) while components are how software is organized (e.g.,shared services and platforms such as data management).

As an organization grows, we see both the feature and component sides scale. Feature teams start to diverge into multiple products, while component teams continue to grow in the guise of shared services and platforms. Their concerns continue to differentiate, and communication friction may start to emerge between the teams. How an organization handles this is critical.

In a world of digital products delivered as services, both feature and component teams may be the recipients of ongoing investment. An ongoing objection in discussions of Agile is, “We can’t put a specialist on every team!” This objection reflects the increasing depth of specialization seen in the evolving digital organization. Ultimately, it seems there are two alternatives to handling deep functional specialization in the modern digital organization:

-

Split it across teams

-

Turn it into an internal product

We’ve discussed the first option above (split the specialty across teams). But for the second option consider for example the traditional role of server engineer (a common infrastructure function). Such engineers historically have had a consultative, order-taking relationship to application teams:

-

An application team would identify a need for computing capacity (“we need four servers”)

-

The infrastructure engineers would get involved and provide recommendations on make, model, and capacity

-

Physical servers would be acquired, perhaps after some debate and further approval cycles

Such processes might take months to complete, and often caused dissatisfaction. With the rise of cloud computing, however, we see the transition from a consultative, order-taking model to an automated, always-on, self-service model. Infrastructure organizations move their activities from consulting on particular applications to designing and sustaining the shared, self-service platform. At that point, are they a function or a product?

9.5. Final thoughts on organization forms

Formal organizational structures determine, to a great extent, how work gets done. But enterprise value requires that organizational units -— whether product or functional -— collaborate and coordinate effectively. Communications structures and interfaces, as covered in Chapter 7, are therefore an essential part of organizational design.

And of course, an empty structure is meaningless. You need to fill it with real people, which brings us to the topic of human resource management in the digital organization.

9.6. IT human resource management

Now that you have decided, for now, on an organization structure, you need to put people into it. As you scale, hiring people (like managing money) becomes a practice requiring formalization, and you will doubtless need to hire your first HR professional soon, in order to stay compliant with applicable laws and regulations.

9.6.1. Basic concerns

Human Resource management can also be termed "people management.” It is distinct from supply chain and technology management, being concerned with the identification and recruitment, onboarding, ongoing development of, and eventual exit of individuals from an organization. This brief section covers the topic as it relates to digital management, incorporating recent cases and perspectives.

9.6.2. Hiring

hiring is one of the most important things a software organization does. Every good hire accelerates your organization; every poor hire is a drag on your organization.

Agile Hiring

In procedural work, the best are 2x better than the average. In creative/inventive work, the best are 10x better than the average, so [we place a] huge premium on creating effective teams of the best.

Netflix Culture: Freedom and Responsibility

Here is a typical hiring process:

-

Solicit candidates, through various channels such as job boards and recruiters

-

Review resumes and narrow candidate pool down for phone interviews

-

Conduct phone interviews and narrow candidate pool down for in person interviews

-

Conduct in person interviews, identify candidates for offers

-

Make offer, negotiate to acceptance

-

Hire and onboard

Your organization has been hiring people for some time now. It’s always been one of your most important decisions, but you have reached the point where a more formal and explicit understanding of how you do this is essential.

First, why do you hire new staff? How and when do you perceive a need? It is well established that increasing the size of a team can slow it down. Legendary software engineer Fred Brooks, in his work The Mythical Man Month, identified the pattern that “adding more people to a late project makes it later” [37].

Are you adding people because of a perceived need for specialist skills? While this will always be a reason for new hires, many argue in favor of “T-shaped” people — people who are deep in one skill, and broad in others. Hiring new staff has an impact on culture — is it better to train from within, or source externally?

Second, how are you hiring staff? In a traditional, functionally specialized model, someone in a Human Resources organization acts as an intermediary between the hiring manager, and the job applicant (sometimes with a recruiter also in the mix between the company and the applicant). Detailed job descriptions are developed, and applicants not explicitly matching the selection criteria (e.g.,in their resume) are not invited for an interview.

Such practices do not necessarily result in good outcomes. Applicants routinely tailor resumes to the job description. In some cases, they have been known to copy the job description into invisible sections of their resume so that they are guaranteed a “match” if automated resume-scanning software is used.

A compelling case study of the limitations of traditional HR-driven hiring is discussed by Robert Sutton and Huggy Rao in Scaling up Excellence: Getting to More without Settling for Less [262]. The authors describe the company Lotus Software, one of the pioneers of early desktop computing.

With [company founder] Kapor’s permission, [head of organizational development] Klein pulled together the resumes of the first forty Lotus employees…[and] submitted all forty resumes to the Lotus human resources department. Not one of the forty applicants, including Kapor, was invited for a job interview. The founders had built a world that rejected people like them.

Sean Landis, author of Agile Hiring [241], believes that “accepted hiring wisdom is not very effective when applied to software professionals.” He further states that:

-

very few companies hire well;

-

individuals with deep domain knowledge are in the best position to perform great hiring;

-

companies often focus on the wrong candidates; and

-

it is important to track metrics on the cost and effectiveness of hiring practices.

In short, hiring is one of the most important decisions the digital enterprise makes, and it cannot be reduced to a simple process to be executed mechanically. Requiring senior technical talent to interview candidates may result in improved hiring decisions. However, such requirements add to the overall work demands placed on these individuals.

9.6.3. Process as skill

Sometimes new employees come in expecting that you are following certain processes. This is in part because “process” experience can be an important part of an employee’s career background. A skilled HR manager may consider their experience with large-scale enterprise hiring processes to be a major part of their qualifications for a position in your company.

This applies to both “business” and “IT” processes. In fact, in the digital world, there is no real difference. Digital processes:

-

Initiate new systems, from idea to construction

-

Publicize and grant access to the new systems

-

Capture revenue from the systems

-

Support people in their interactions with the systems

-

Fix the systems when they break

-

Improve the systems based on stakeholder feedback

It’s not clear which of these are “IT” versus “business” processes. But they are definitely processes. Some of them are more predictable, some less so, but they all represent some form of ordered work that is repeatable to some degree. And to some extent, you may be seeking people with experience defined at least in part by their exposure to processes.

9.6.4. Allocation and tracking people’s time

When a new hire enters your organization, they enter a complex system that will structure and direct their daily activities through a myriad of means. The various means that direct their action include:

-

Team assignment (e.g.,to an ongoing product)

-

Project assignment

-

Process responsibilities

Notice again the appearance of the "3 Ps."

Product, project, and process become challenging when they are all allowed to generate demand on individuals independently of each other. In the worst case scenario, the same individual winds up with:

-

Collaborative team responsibilities

-

“Fractional” allocation to one or more projects

-

Ticketed process responsibilities

|

Note

|

Fractional allocation is the practice of funding individuals through assigning them at some % to a project. For example, a server engineer might be allocated 25% time to a project for 6 months to define its infrastructure architecture, while being assigned 30% to another project to refresh obsolete infrastructure. |

When demand is un-coordinated, these multiple channels can result in multi-tasking and dramatic overburden, and in the worst case, the individual becomes the constraint to enterprise value. Project managers expect deliverables on time, and too often have no visibility to operational concerns (e.g.,outages) that may affect the ability of staff to deliver. Ad hoc requests “smaller than a project, bigger than a ticket” further complicate matters.

The Phoenix Project presents an effective and realistic dramatization of the resulting challenges. Work is entering the system through multiple channels, and the overburden on key individuals (such as Brent, the lead systems engineer) has reached crisis proportions. Through a variety of mechanisms, they take control of the demand channels and greatly improve the organization’s success. One of the most important lessons is well articulated by Erik, the mentor:

“Your job as VP of IT Operations is to ensure the fast, predictable, and uninterrupted flow of planned work that delivers value to the business while minimizing the impact and disruption of unplanned work, so you can provide stable, predictable, and secure IT service…You must figure out how to control the release of work into IT Operations and, more importantly, ensure that your most constrained resources are doing only the work that serves the goal of the entire system, not just one silo. [153 p. 91+]+

In order to understand the work, measuring the consumption of people’s time is important. There are various time tracking approaches:

-

Simple allocation of staff payroll to product or organizational line

-

Project management systems (sometimes these are used for weekly time tracking, even for staff that are not assigned to projects — in such cases, placeholder operational projects are created)

-

Human Resource Management systems

-

Ticketing/workflow systems — advanced systems, such as those found in the Professional Services Automation sector, track time when tickets are in an “open” status.

-

Backlog management systems (that may seem similar to ticketing systems)

-

Home built systems

There is little industry consensus on best practices here. There are reasonable concerns about the burden of time tracking on employees, and poor data quality resulting from employees attempting to “code” activities when summarizing their time on a weekly or bi-weekly basis. [3]

9.6.5. Accountability and performance

When individuals in a system are forced to compete with others’ accomplishments, this increases the challenge of effective collaboration. Clear, transparent communication is not perceived as valuable to the individual, as having information can impact rewards, career advancement, and even whether an individual has a job.

Effective DevOps

Regardless of whether the company is a modern digital enterprise or more traditional in its approach, the commitment, performance, and results of employees is a critical concern. The traditional approach to managing this has been an annual review cycle, resulting in a performance ranking from 1-5:

-

Did not meet expectations

-

Partially met expectations

-

Met expectations

-

Exceeded expectation

-

Significantly exceeded expectations

This annual rating determines the employee’s compensation and career prospects in the organization. Some companies, notably GE and Microsoft, have attempted “stack rankings” in which the “bottom” 10% (or more) performers must be terminated. As the Davis and Daniels quote above indicates, such practices are terribly destructive of psychological safety and therefore team cohesion. High profile practitioners are therefore moving away from this practice [39], [201].

The traditional annual review is a large “batch” of feedback to the employee, and therefore ineffective in terms of systems theory, not much better than an open-loop approach. Because of the weaknesses of such slow feedback (not to mention the large annual costs, expensive infrastructure, and opportunity costs of the time spent), companies are experimenting with other approaches.

Deloitte Consulting, as reported in the Harvard Business Review [41], realized that its annual performance review process was consuming two million hours of time annually, and yet was not delivering the needed value. In particular, ratings were suffering from the measurable flaw that they tended to reveal more about the person doing the rating, than the person being rated!

They started by redefining the goals of the performance management system to identify and reward performance accurately, as well as further fueling improvements.

A new approach with greater statistical validity was implemented, based on four key questions:

-

Given what I know of this person’s performance, and if it were my money, I would award this person the highest possible compensation increase and bonus

-

Given what I know of this person’s performance, I would always want him or her on my team

-

This person is at risk for low performance

-

This person is ready for promotion today

In terms of the frequency of performance check-ins, they note:

the best team leaders … conduct regular check-ins with each team member about near term work . . . to set expectations for the upcoming week, review priorities, comment on recent work and provide course correction, coaching, or important new information…If a leader checks in less often than once a week, the team member’s priorities may become vague . . . the conversation will shift from coaching for near term work to giving feedback about past performance…If you want people to talk about how to do their best work in the near future, they need to talk often…

Sutton and Rao, in Scaling up Excellence, discuss the similar case of Adobe. At Adobe, “annual reviews required 80,000 hours of time from the 2,000 managers at Adobe each year, the equivalent of 40 full-time employees. After all that effort, internal surveys revealed that employees felt less inspired and motivated afterwards— and turnover increased.” Because of such costs and poor results, Adobe scrapped the entire performance management system in favor of a “check-in” approach. In this approach, managers are expected to have regular conversations about performance with employees and are given much more say in salaries and merit increases. The managers themselves are evaluated through random “pulse surveys” that measure how well each manager “sets expectations, gives and receives feedback, and helps people with their growth and development.” [262 p. 113].

Whether incentives (e.g.,pay raises) should be awarded individually or on a team basis is an ongoing topic of discussion in the industry. Results often derive from team performance, and the contributions of any one individual can be difficult to identify. Because of this, Scrum pioneer Ken Schwaber argues that “The majority of the enterprise’s bonus and incentive funds need to be allocated based on the team’s performance rather than the individual’s performance.” [238 p. 6]. However, this runs into another problem: that of the “free-rider.” What do we do about team members who do not pull their weight? Even in self-organizing teams, confronting someone about their behavior is not something people do willingly, or well.

Ideally, teams will self-police, but this becomes less effective with scale. In one case study in the Harvard Business Review, Continental Airlines found that the free rider problem was less of a concern when metrics were clearly correlated with team activity. In their case, the efforts and cooperation of gate teams had a significant influence on On-Time Arrival and Departure metrics, which could then be used as the basis for incentives [156].

Ultimately, both individuals and teams need coaching and direction. Team-level management and incentives must still be supplemented with some feedback loops centering on the individual. Perhaps this feedback is not compensation-based, but the organization must still identify individuals with leadership potential and deal with free riders and toxic individuals.

Observed behaviors are a useful focus. Sean Landis describes the difference between behaviors and skills thus:

Two things make good leaders: behaviors and skills. If you focus on behaviors in your hiring of developers, they will be predisposed for leadership success. The hired candidate may walk in the door with the skills necessary to lead or not. If not, skills are easy to acquire through training and mentoring. People can acquire or modify behaviors, but it is much harder than skill development. Hire for behaviors and train the leadership skills. [241+]+

He further provides many examples of behaviors, such as:

-

Adaptable

-

Accountable

-

Initiative Taker

-

Optimistic

-

Relational

Many executives and military leaders have identified the central importance of hiring decisions. In large, complex organizations, choosing the right people is the most powerful lever a leader has to drive organizational performance. The organizational context these new hires find themselves in will profoundly affect them and the results of their efforts.

9.7. Why culture matters

What is culture in this context? It is not so much about an informal dress code, flexible hours, or a free in-house cafeteria as it is about how decisions are taken, norms of behavior, protocols of communication, and the ways of navigating hierarchy and bureaucracy to get things done.

Agile IT Organization Design

“Culture” is a difficult term to define, and even more difficult to characterize across large organizations. It starts with how an organization is formally structured, because structure is, in part, a set of expectations around how information flows. “Who talks to who, when and why” is in a sense culture. Culture can also be seen embedded in artifacts like processes and formally specified operating models.

But “culture” has additional, less tangible meanings. The anecdotes executives choose to repeat are culture. Whether an organization tacitly condones being 5 minutes late for meetings (because walk time in large facilities is expected) or has little tolerance for this (because most people dial in) is culture. The degree of deference shown to senior executives, and their opinions, is culture. Whether a junior person dares to hit “reply-all” on an email including her boss’s boss is culture. Organizational tolerance for competitive or toxic behavior is culture.

Culture cannot be directly changed — it is better seen as a lagging indicator, that changes in response to specific practical interventions. Even tools and processes can change the culture, if they are judiciously chosen (most tools and processes do not have this effect). Skeptical? Consider the impact that computers — a tool — have had on culture. Or email.

We’ve already touched on culture in the chapter 4 discussion of team formation. These themes of psychological safety, equal collaboration, emotional awareness, and diversity inform our further discussions. We’ll look at culture from a few additional perspectives in this section:

-

Motivation

-

Schneider matrix

-

The Westrum typology

-

Mike Rother’s research into Toyota’s improvement and coaching “katas”

9.7.1. Motivation

One of the most important reasons to be concerned about culture is its effect on motivation. There is little doubt that a more motivated team performs better than an unmotivated, “going through the motions” organization. But what motivates people?

One of the oldest discussions of culture is Douglas McGregor’s idea of "Theory X” versus “Theory Y" organizations, which he developed in the 1960s at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Theory X organizations rely on extrinsic motivators and operate on the assumption that workers must be cajoled and punished in order to produce results. We see Theory X approaches when organizations focus on pay scales, bonuses, titles, awards, writeups/demerits, performance appraisals, and the like.

Theory Y organizations operate on the assumption that most people seek meaningful work intrinsically and that they have the ability to solve problems in creative ways that do not require tight standardization. According to Theory Y, people can be trusted and should be treated as mature individuals, in contrast to the distrust inherent in Theory X.

Related to Theory Y, in terms of intrinsic motivation, Daniel Pink, the author of Drive, suggests that three concepts are key: autonomy, mastery, and purpose. If these three qualities are experienced by individuals and teams, they will be more likely to feel motivated and collaborate more effectively.

9.7.2. Schneider and Westrum

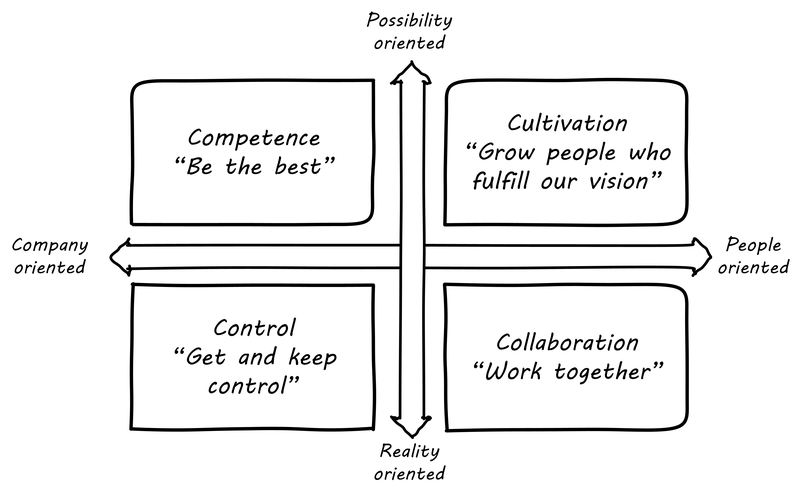

One model for understanding culture is the matrix proposed by William Schneider (see Schneider matrix) [4].

Two dimensions are proposed:

-

the extent to which the culture is focused on the company or the individual

-

the extent to which the company is “possibility-oriented” versus “reality-oriented”

This is not a neutral matrix. It’s not clear that highly controlling cultures are ever truly effective. Even in the military, which is generally assumed to be the ultimate “command and control” culture, there are notable case studies of increased performance when more empowering approaches were encouraged.

Similar to the Schneider matrix is the Westrum typology, which proposes that there are three major types of culture:

-

Pathological

-

Bureaucratic

-

Generative

The cultural types exhibit the following behaviors:

| Pathological (Power-oriented) | Bureaucratic (Rule-oriented) | Generative (Performance-oriented) |

|---|---|---|

Low cooperation |

Modest cooperation |

High cooperation |

Messengers (of bad news) shot |

Messengers neglected |

Messengers trained |

Failure is punished |

Failure leads to justice |

Failure leads to inquiry |

(excerpted from [215])

The State of DevOps research has demonstrated a correlation between generative cultures and digital business effectiveness [215], [38]. Notice also the relationship to blameless postmortems discussed in Chapter 6.

9.7.3. Toyota Kata

Six years ago I began the research that led to [Toyota Kata] thinking, like just about everyone else, that the story was about techniques and other listable aspects of Toyota. Today I see Toyota in a notably different light: as an organization defined primarily by the unique behavior routines, it continually teaches to all its members.

Toyota Kata

Academics and consultants have been studying Toyota for many years. The performance and influence of the Japanese automaker are legendary, but it has been difficult to understand why. Much has been written about Toyota’s use of particular tools, such as Kanban bins and andon boards. However, Toyota views these as ephemeral adaptations to the demands of its business.

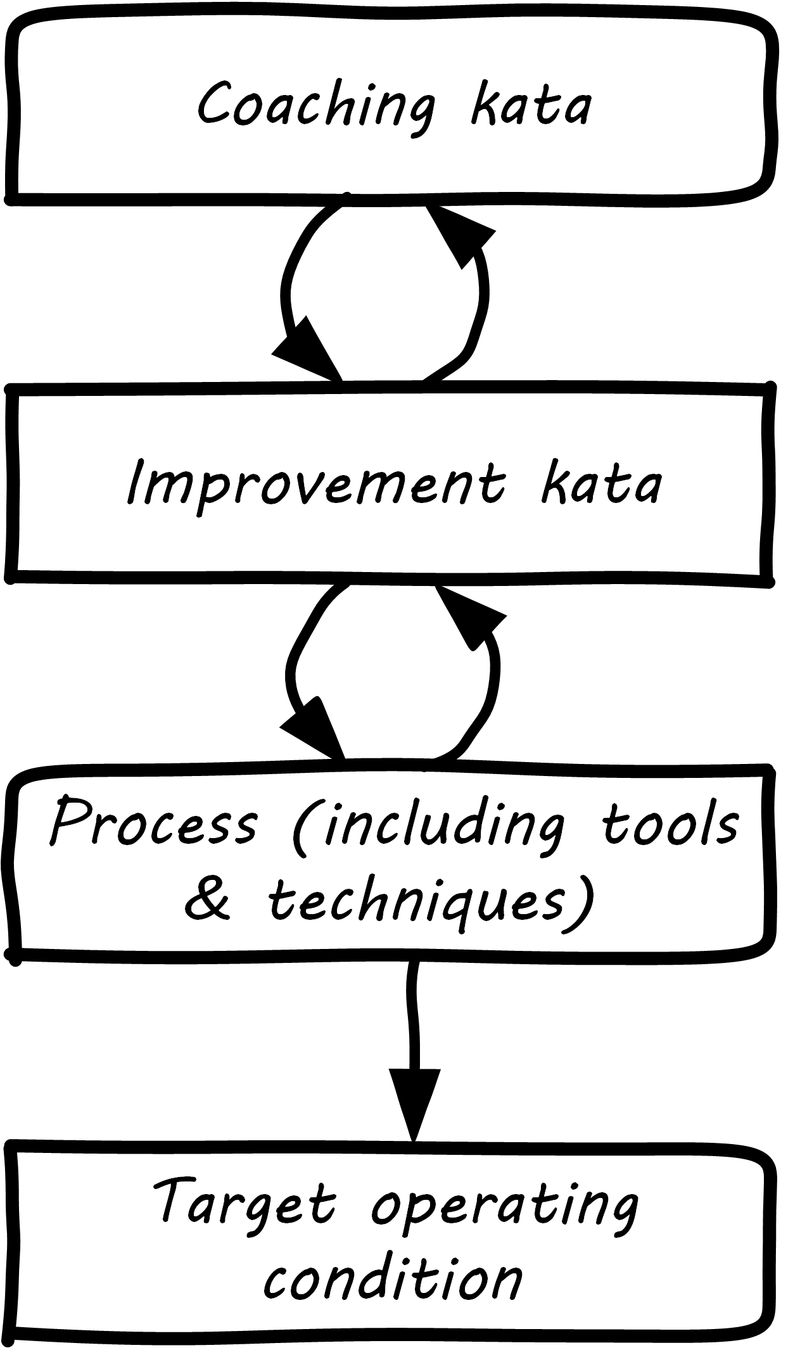

According to Mike Rother in Toyota Kata [227], underlying Toyota’s particular tools and techniques are two powerful practices:

-

The improvement kata

-

The coaching kata

What is a kata? It is a Japanese word stemming from the martial arts, meaning pattern, routine, or drill. More deeply, it means “a way of keeping two things in alignment with each other.” The improvement kata is the repeated process by which Toyota managers investigate and resolve problems, in a hands-on, fact-based, and preconception-free manner, and improve processes towards a “target operating condition.” The coaching kata is how the improvement kata is instilled in new generations of Toyota managers (see Toyota kata, [5]).

As Rother describes it, the coaching and improvement katas establish and reinforce a coherent culture or mental model of how goals are achieved and problems approached. It is understood that human judgment is not accurate or impartial. The method compensates with a teaching-by-example focus on seeking facts without preconceived notions, through direct, hands-on investigation and experimental approaches.

This is not something that can be formalized into a simple checklist or process; it requires many guided examples and applications before the approach becomes ingrained in the upcoming manager.

9.8. Industry frameworks

Having discussed organizational structure, hiring, and culture, we will now turn to a critical examination of the IT management frameworks.

Industry frameworks and bodies of knowledge play a powerful role in shaping organizational structures and their communication interfaces, and creating a base of people with consistent skills to fill the resulting roles. While there is much of value in the frameworks, they may lead you into the planning fallacy or defined process traps. Too often, they assume that variation is the enemy, and they do not provide enough support for the alternative approach of empirical process control. As of this writing, the frameworks are challenged on many fronts by Agile, Lean, and DevOps approaches.

9.8.1. Defining frameworks

|

Note

|

There are other usages of the term “framework,” especially in terms of software frameworks. Process and management frameworks are non-technical. |

So, what is a “framework?”

The term “framework,” in the context of a business process, is used for comprehensive and systematic representations of the concerns of a professional practice. In general, an industry framework is a structured artifact that seeks to articulate a professional consensus regarding a domain of practice. The intent is usually that the guidance be mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive within the domain so that persons knowledgeable in the framework have a broad understanding of domain concerns.

The first goal of any framework, for a given conceptual space, is to provide a “map” of its components and their relationships. Doing this serves a variety of goals:

-

Develop and support professional consensus in the business area

-

Support training and orientation of professionals new to the area (or its finer points)

-

Support governance and control activities related to the area (more on this in Chapter 10)

Many frameworks have emerged in the IT space, with broader and narrower domains of concern. Some are owned by non-profit standards bodies; others are commercial. We will focus on five in this book. In roughly chronological order, they are:

-

CMMI (Capability Maturity Model-Integrated)

-

ITIL (originally the Information Technology Infrastructure Library)

-

PMBOK (The Project Management Body of Knowledge)

-

CObIT (aka Control Objectives for Information Technology)

-

The TOGAF® framework (The Open Group standard for Enterprise Architecture)

The frameworks are summarized in the appendix.

9.8.2. Observations on the frameworks

In terms of the new digital delivery approaches, there are a number of issues and concerns with the frameworks:

-

The fallacy of statistical process control

-

Local optimization temptation

-

Lack of execution model

-

Proliferation of secondary artifacts, compounded by batch orientation

-

Confusion of process definition

The problem of statistical process control

CMM author Watts Humphrey’s original vision was to apply full statistical process control to the software process. As he stated at the time:

Dr. W. E. Deming, in his work with the Japanese after World War II, applied the concepts of statistical process control to many of their industries. While there are important differences, these concepts are just as applicable to software as they are to producing consumer goods like cameras, television sets, or auto mobiles [130 p. 3].

The overall CMM/CMMI idea (in the original staged model) is that a process cannot be improved and optimized until it is fully under control. Perhaps well-defined industrial processes should not be optimized until they are fully “managed.” However, as we discussed in the previous section, process control theorists see creative, knowledge-intensive processes as requiring empirical control. Statistical process control applied to software has therefore been criticized as inappropriate [217].

In CMM terms, empirical process control starts by measuring and immediately optimizing (adjusting). To restate the Martin Fowler quote from the last section: “a process can still be controlled even if it can’t be defined."[240] They need not — and cannot — be fully defined. Therefore, one of the most questionable aspects of CMMI is its implication that process optimization is something only done at the highest levels of maturity.

In short, the CMMI staged model encourages the thought that process improvement (optimization) only is possible at Level 5. Many companies implementing CMMI stages, however, will pragmatically say “Maybe we only need to get to level 3.” This implies that they define and manage their processes, but never improve them.

This runs against much current thinking and practice, especially that deriving from Lean philosophy, in which processes are seen as always under improvement. (See discussion of Toyota Kata. All definition, measurement, and control must serve that end.

The CMMI has evolved since Humphrey’s initial vision, but between its mis-applicaton of statistical process control, and the idea that that process optimization is only relevant at the highest maturity, it is (in the view of this author) badly out of step with current digital trends.

The other frameworks do not embrace statistical process control to the same extent as the CMMI. PMBOK suggests that “control charts may also be used to monitor cost and schedule variances, volume, and frequency of scope changes, or other management results to help determine if the project management processes are in control” [214 pp. 4108-4109]. This also contradicts the insights of empirical process control, unless the project were also a fully defined process — unlikely from a process control perspective.

Local optimization temptation

We must not seek to optimize every resource in the system … A system of local optimums is not an optimum system at all; it is a very inefficient system.

The Goal

IT capability frameworks can be harmful if they lead to fragmentation of improvement effort and lack of focus on the flow of IT value.

The digital delivery system at scale is a complex socio-technical system, including people, process, and technology. Frameworks help in understanding it, by breaking it down into component parts in various ways. This is all well and good, but the danger of reductionism emerges.

|

Note

|

There are various definitions of "reductionism.” This discussion reflects one of the more basic versions. |

A reductionist view implies that a system is nothing but the sum of its parts. Therefore, if each of the parts is attended to, the system will also function well.

This can lead to a compulsive desire to do “all” of a framework. If ITIL calls for 25 processes, then a large, mature organization by definition should be good at all of them. But the 25 processes (and dozens more sub-processes and activities) called for by ITIL, or the 32 called for by CObIT, are somewhat arbitrary divisions. They overlap with each other. Furthermore, there are many digital organizations that do not use the full ITIL or CObIT process portfolio and yet deliver value as well as organizations that do use the frameworks to a greater degree.

The temptation for local, process-level optimization runs counter to core principles of Lean and systems thinking. Many management thinkers, including W.E. Deming, Eli Goldratt, and others have emphasized the dangers of local optimization and the need for taking a systems view.

As this book’s structure suggests, the delivering of IT value requires different approaches at different scales. There is recognition of this among framework practitioners; however, the frameworks themselves provide insufficient guidance on how they scale up and down.

Lack of execution model

It is also questionable whether even the largest actual IT organizations on the planet could fully implement the frameworks. Specifying too many interacting processes has its own complications. Consider: Both ITIL and CObIT devote considerable time to documenting possible process inputs and outputs. As a part of every process definition, ITIL has a section entitled “Triggers, inputs, outputs, and interfaces.” The “Service Level Management Process” [265 pp. 120-122] for example, lists:

-

7 triggers (e.g.,“service breaches”)

-

10 inputs (e.g.,“customer feedback”)

-

10 outputs (e.g.,“reports on OLAs”)

-

7 interfaces (e.g.,“Supplier management”)

CObIT similarly details process inputs and outputs. In the Enabling Processes guidance, each management practice suggests inputs and outputs. For example, the APO08 process “Manage Relationships” has an activity of “Provide input to the continual improvement of services,” with

-

6 inputs

-

2 outputs

But processes do not run themselves. These process inputs and outputs require staff attention. They imply queues and therefore work in process, often invisible. They impose a demand on the system, and each handoff represents transactional friction. Some handoffs may be implemented within the context of an IT management suite; others may require procedural standards, which themselves need to be created and maintained. The industry currently lacks understanding of how feasible such fully elaborated frameworks are in terms of the time, effort, and organizational structure they imply.

We have discussed the issue of overburden previously. Too many organizations have contending execution models, where projects, processes, and miscellaneous work all compete for people’s attention. In such environments, the overburden and wasteful multi-tasking can reach crisis levels. With ITIL in particular, because it does not cover project management or architecture, we have a very large quantity of potential process interactions that is nevertheless incomplete.

Secondary artifacts, compounded by batch orientation

We move away from heavily documented handoffs to a process that creates only the design artifacts we need to move the team’s learning forward.

Lean UX

The process handoffs also imply that artifacts (documents of various sorts, models, software, etc.). are being created and transferred in between teams, or at least between roles on the same team with some degree of formality. Primary artifacts are executable software and any additional content intended directly for value delivery. Secondary artifacts are anything else.

An examination of the ITIL and CObIT process interactions shows that many of the artifacts are secondary concepts such as “plans,” “designs,” or “reports:”

-

Design specifications (high level and detailed)

-

Operation and use plan

-

Performance reports

-

Action plans

-

Consideration and approval

and so on. (Note that actually executable artifacts are not included here).

Again, artifacts do not create themselves. Hundreds of artifacts are implied in the process frameworks. Every artifact implies:

-

Some template or known technique for performing it

-

People trained in its creation and interpretation

-

Some capability to store, version, and transmit it

Unstructured artifacts such as plans, designs, and reports, in particular, impose high cognitive load and are difficult to automate. As digital organizations automate their pipelines, it becomes essential to identify the key events and elements they may represent, so that they can be embedded into the automation layer.

Finally, even if a given process framework does not specifically call for waterfall, one can sometimes still see its legacy. For example:

-

Calls for thorough, “rigorous” project planning and estimation

-

Cautions against “cutting corners”

-

“Design specifications” moving through approval pipelines (and following a progression from general to detailed)

All of these tend to signal a large batch orientation, even in frameworks making some claim of supporting Agile.

Good system design is a complex process. We introduced technical debt in Chapter 3, and will revisit it in Chapter 12. But the slow feedback signals resulting from the batch processes implied by some frameworks are unacceptable in current industry. This is in part why new approaches are being adopted.

Confusion of process definition

One final issue with the “process” frameworks is that, while they use the word “process” prominently, they are not aligned with Business Process Management best practices [23].

All of these frameworks provide useful descriptions of major ongoing capabilities and practices that the large IT organization must perform. But in terms of our preceding discussion on process method, they, in general, are developed from the perspective of steady-state functions, as opposed to a value stream or defined process perspective.

This can be seen by looking above at ITIL, for example. A Business Process Management consultant would see the term “Capacity Management” and observe that it is not countable or event-driven. “How many Capacities did you do today? ” is not a sensible question, for the most part.

The BPM community is clear that processes and countable and event-driven (see [245]). Naming them with a strong, active verb is seen as essential. “True” IT processes, therefore, might include:

-

Accept Demand

-

Deliver Release

-

Complete Change

-

Resolve Incident

-

Improve Service

Conclusion

Organizational development is always an ongoing process of balancing culture, centralization, and autonomy. Rather than seeking any “best practice,” it is better to see a toolbox, or perhaps a set of levers you can position in various ways to get different results. As of 2015, product-centric Agile teams are becoming more and more common. But there are ultimately limitations to this approach, which many companies have experienced.

Culture can be difficult to define. We saw how Toyota’s success could be understood as a strategy of ingraining particular cultural understandings through pervasive coaching.

Finally, hiring and managing people is a critical concern for digital organizations as with all organizations. Issues of motivation and accountability are becoming better understood, and practices recently seen as “best” (such as forced ranking) are now being abandoned in favor of more team-oriented approaches.

Discussion questions

-

What kinds of organizational structures have you worked in?

-

What do you prefer?

-

Think about organizations you know and discuss them in terms of the Schneider matrix and/or the Westrum typology.

-

Have you ever worked with a toxic or unaccountable person? Was their behavior promptly confronted, or was it allowed to persist?

Research & practice

-

Research the history of the original Lockheed Martin Skunkworks under Kelly Martin.

-

Compare and contrast holacracy (look it up) and skunkworks.

-

As a class, group yourself into the various organizational forms and route simple paper-based work between each other, or undertake simple craft projects such as building a Lego set as a team.

-

Research the Agile concept of “team” and in particular how the “team” should interact with external forces.

-

Research the current viewpoints on McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y.

-

Compare and contrast the Scaled Agile Framework and CObIT.

Further reading

Books

-

Fred Brooks, The Mythical Man-Month

-

Tom DeMarco, Timothy Lister, Peopleware

-

Paul Glen, Leading Geeks

-

Henry Mintzberg, Structure in Fives

-

Sriram Narayam, Agile IT Organization Design

-

Daniel Pink, Drive

-

Mike Rother, Toyota Kata: Managing People for Improvement, Adaptiveness, and Superior Results

-

Preston G. Smith, Donald G. Reinertsen, Developing Products in Half the Time: New Rules, New Tools

Articles

-

Melvin Conway, How Do Committees Invent? (original statement of Conway’s Law)

-

Charles Duhigg, What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team

-

Joseph Flahiff, How organizational agility will save and destroy your company

-

Paul Glen, 11 Ways to Motivate Geeks

-

Bill Goodwin, How CIOs can raise their 'IT clock speed' as pressure to innovate grows

-

Reed Hastings, Netflix Culture: Freedom and Responsibility

-

Henrik Kniberg, Scaling Agile @ Spotify with Tribes, Squads, Chapters & Guilds

-

Jason Little, The Marriage of Agile and Organizational Change Management

-

Kermit Pattison, Worker, Interrrupted: The Cost of Task Switching

-

Dave Roberts, Why “Enterprise DevOps” Doesn’t Make Sense

-

Steve Sinofsky, Functional versus Unit Organizations

-

Sosa et al., The Misalignment of Product Architecture and Organizational Structure in Complex Product Development (Research supporting Conway’s Law)

Videos

Other resources

-

Matthew Skelton, How and why to design your Teams for modern Software Systems

-

Lloyd Taylor, Hacking your organization

In addition to the above books, the resources available on organizational design at smaller scales are vast, as these are very frequently asked questions by entrepreneurs of all types. Some useful links are: