7. Coordination

7.1. Introduction

coordination (n). co-ordination, c. 1600, “orderly combination,” from French coordination (14c). or directly from Late Latin coordinationem (nominative coordinatio), noun of action from past participle stem of Latin coordinare “to set in order, arrange,” from com— “together” (see com-) + ordinatio “arrangement,” from ordo “row, rank, series, arrangement” (see order (n)). Meaning “action of setting in order” is from the 1640s; that of “harmonious adjustment or action,” especially of muscles and bodily movements, is from 1855.

Agile software development methods were particularly designed to deal with change and uncertainty, yet they de-emphasize traditional coordination mechanisms such as forward planning, extensive documentation, specific coordination roles, contracts, and strict adherence to a pre-specified process [258].

Coordination in co-located agile software development projects

Growth is presenting us with many challenges. But we can’t stop too long and think about how to handle it. We have to continue executing, as we scale up. The problem is like changing the tires on a moving car. It’s not easy.

We’ve been executing our objectives since our first day in the garage. As noted above, execution is whenever we meet demand with supply. An idea for a new feature, to deliver some digital value, is demand. The time we spend implementing the feature is supply. The two combined is execution. Sometimes it goes well; sometimes it doesn’t. Maintaining a tight feedback loop to continually assess our execution is essential.

As we grow into multiple teams and multiple products, we have more complex execution problems, requiring coordination. The fundamental problem is the “D-word:” dependency. Dependencies are why we coordinate (work with no dependencies can scale nicely along the AKF x-axis). But when we have dependencies (and there are various kinds) we need a wider range of techniques. Our one Kanban board is not sufficient to the task.

We need to consider the delivery models, as well (the “3 Ps": product, project, process, and now we’ve added program management). Decades of industry practice mean that people will tend to think in terms of these models and unless we are clear in our discussions about the nature of our work we can easily get pulled into non-value-adding arguments. To help our understanding, we’ll take a deeper look at process management, continuous improvement, and their challenges.

7.1.1. Chapter overview

In this section, we will cover:

-

Defining coordination

-

Coordination & dependencies

-

Concepts and techniques

-

Coordination effectiveness

-

-

Coordination, execution, and the delivery models

-

Product management and coordination

-

Project management as coordination

-

Process management as coordination

-

-

A deeper examination of process management

-

Process control and continuous improvement

There is a discussion of business process modeling fundamentals in the appendix.

7.1.2. Chapter learning objectives

-

Identify and describe dependencies, coordination, and their relationship

-

Describe the relationship of delivery models to coordination

-

Describe process management and its strengths and weaknesses as a coordination mechanism

-

Identify the problems of process proliferation with respect to execution and demand

-

Identify key individuals and themes in the history of continuous improvement

-

Describe the applicability of statistical process control to different kinds of processes

7.2. Defining coordination

7.2.1. Example: Scaling one product

Good team structure can go a long way toward reducing dependencies but will not eliminate them.

Succeeding with Agile

What’s typically underestimated is the complexity and indivisibility of many large-scale coordination tasks.

preface to the Open Organization: Igniting Passion and Performance

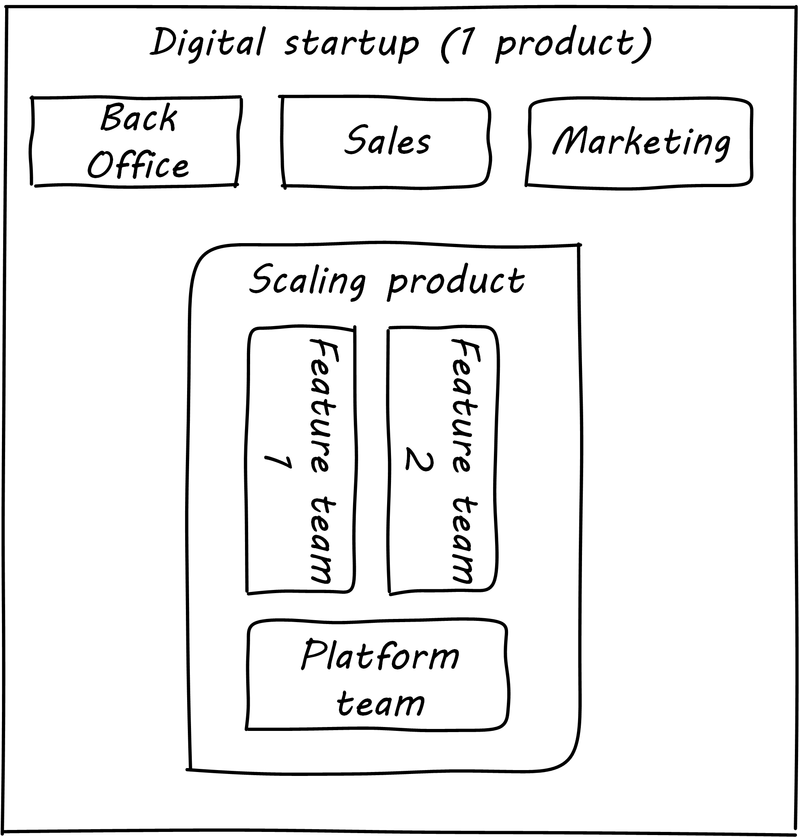

We’ve defined execution as the point at which supply and demand are combined, and of course, we’ve been executing since the start of our journey. Now, however, we are executing in a more complex environment; we have started to scale along the AKF scaling cube y-axis, and we have either multiple teams working on one product and/or multiple products. Execution becomes more than just “pull another story off the Kanban board.” As multiple teams are formed (see Multiple feature teams, one product), dependencies arise, and we need coordination. The term "architecture” is likely emerging through these discussions. (We will discuss organizational structure directly in Chapter 9, and architecture in Chapter 12).

As noted in the discussion of Amazon’s product strategy, some needs for coordination may be mitigated through the design of the product itself. This is why APIs and microservices are popular architecture styles. If the features and components have well defined protocols for their interaction and clear contracts for matters like performance, development on each team can move forward with some autonomy.

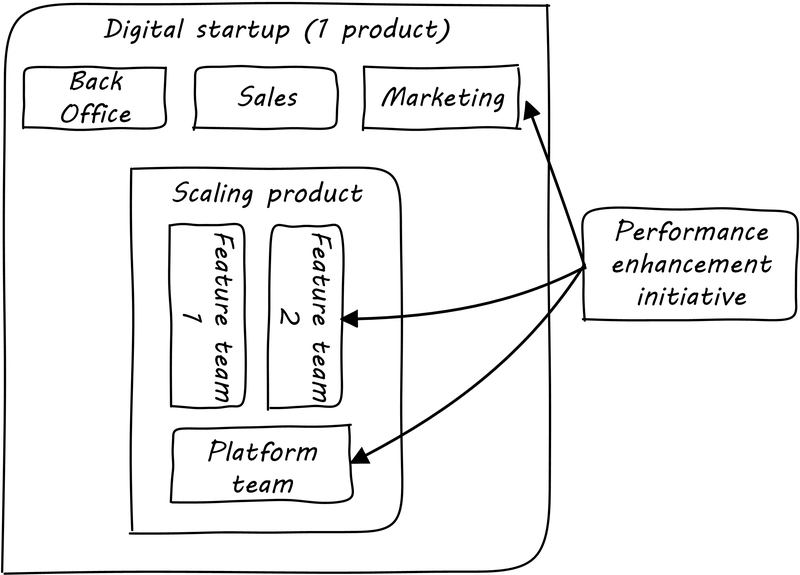

But at scale, complexity is inevitable. What happens when a given business objective requires a coordinated effort across multiple teams? For example, an online e-commerce site might find itself overwhelmed by business success. Upgrading the site to accommodate the new demand might require distinct development work to be performed by multiple teams (see Coordinated initiative across timeframes).

As the quote from Gary Hamel above indicates, a central point of coordination and accountability is advisable. Otherwise, the objective is at risk. (It becomes “someone else’s problem.”) We will return to the investment and organizational aspects of multi-team and multi-product scaling in Chapters 8 and 9. For now, we will focus on dependencies and operational coordination.

7.2.2. A deeper look at dependencies

…coordination can be seen as the process of managing dependencies among activities.

The interdisciplinary study of coordination

What is a "dependency"? We need to think carefully about this. According to the definition above (from [178]), without dependencies, we do not need coordination. (We’ll look at other definitions of coordination in the next two chapters). Diane Strode and her associates [258] have described a comprehensive framework for thinking about dependencies and coordination, including a dependency taxonomy, an inventory of coordination strategies, and an examination of coordination effectiveness criteria.

To understand dependencies, Strode et al. [259] propose the framework shown in Dependency taxonomy (from Strode) footnote:[adapted from [259].

| Type | Dependency | Description |

|---|---|---|

Knowledge. A knowledge dependency occurs when a form of information is required in order for progress. |

Requirement |

Domain knowledge or a requirement is not known and must be located or identified. |

Expertise |

Technical or task information is known only by a particular person or group. |

|

Task allocation |

Who is doing what, and when, is not known. |

|

Historical |

Knowledge about past decisions is needed. |

|

Task. A task dependency occurs when a task must be completed before another task can proceed. |

Activity |

An activity cannot proceed until another activity is complete. |

Business process |

An existing business process causes activities to be carried out in a certain order. |

|

Resource. A resource dependency occurs when an object is required for progress. |

Entity |

A resource (person, place or thing) is not available. |

Technical |

A technical aspect of development affects progress, such as when one software component must interact with another software component. |

We can see examples of these dependencies throughout digital products. In the next section, we will talk about coordination techniques for managing dependencies.

7.2.3. Organizational tools and techniques

Where leveraging yellow stickies or index cards makes sense in conjunction with practices like big visible charts and co-location, such formats become ridiculous for a large constituency of challenging projects. When faced with these challenges, rather than proclaim that Agile won’t work or doesn’t scale, the preferable approach is to understand and acknowledge the nature of collaboration, the nature of distributed workflow, and the complexity of modern product development.

SDLC 3.0

Our previous discussion of work management was a simple, idealized flow of uniform demand (new product functionality, issues, etc.). Tasks, in general, did not have dependencies, or dependencies were handled through ad hoc coordination within the team. We also assumed that resources (people) were available to perform the tasks; resource contention, while it certainly may have come up, was again handled through ad hoc means. However, as we scale, simple Kanban and visual Andon are no longer sufficient, given the nature of the coordination we now require. We need a more diverse and comprehensive set of techniques.

|

Important

|

The discussion of particular techniques is always hazardous. People will tend to latch on to a promising approach without full understanding. As noted by Craig Larman, the risk is one of cargo cult thinking in your process adoption [168 p. 44]. In Chapter 9 we will discuss the Mike Rother book Toyota Kata. Toyota does not implement any procedural change without fully understanding the “target operating condition” -— the nature of the work and the desired changes to it. |

As we scale up, we see that dependencies and resource management have become defining concerns. However, we retain our Lean Product Development concerns for fast feedback and adaptability, as well as a critical approach to the idea that complex initiatives can be precisely defined and simply executed through open-loop approaches. In this section, we will discuss some of the organizational responses (techniques and tools) that have emerged as proven responses to these emergent issues.

|

Note

|

The table Coordination taxonomy (from Strode) uses the concept of artifact, which we introduced in Chapter 5. For our purposes here, an artifact is a representation of some idea, activity, status, task, request, or system. Artifacts can represent or describe other artifacts. Artifacts are frequently used as the basis of communication. |

Strode et al also provide a useful framework for understanding coordination mechanisms, excerpted and summarized into Coordination taxonomy (from Strode) footnote:[adapted from [258].

| Strategy | Component | Definition |

|---|---|---|

Structure |

Proximity |

Physical closeness of individual team members. |

Availability |

Team members are continually present and able to respond to requests for assistance or information |

|

Substitutability |

Team members are able to perform the work of another to maintain time schedules |

|

Synchronization |

Synchronization activity |

Activities performed by all team members simultaneously that promote a common understanding of the task, process, and or expertise of other team members |

Synchronization artifact |

An artifact generated during synchronization activities. |

|

Boundary spanning |

Boundary spanning activity |

Activities (team or individual) performed to elicit assistance or information from some unit or organization external to the project |

Boundary spanning artifact |

An artifact produced to enable coordination beyond the team and project boundaries. |

|

Coordinator role |

A role taken by a project team member specifically to support interaction with people who are not part of the project team but who provide resources or information to the project. |

The following sections expand the three strategies (structure, synchronization, boundary spanning) with examples.

Structure

Don Reinertsen proposes “The Principle of Colocation” which asserts that “Colocation improves almost all aspects of communication” [220 p. 230]. In order to scale this beyond one team, one logically needs what Mike Cohn calls “The Big Room” [67 p. 346].

In terms of communications, this has significant organizational advantages. Communications are as simple as walking over to another person’s desk or just shouting out over the room. It is also easy to synchronize the entire room, through calling for everyone’s attention. However, there are limits to scaling the “Big Room” approach:

-

Contention for key individual’s attention

-

“All hands” calls for attention that actually interests only a subset of the room

-

Increasing ambient noise in the room

-

Distracting individuals from intellectually demanding work requiring concentration, driving multi-tasking and context-switching, and ultimately interfering with their personal sense of flow — a destructive outcome. (See [74] for more on flow as a valuable psychological state).

The tension between team coordination and individual focus will likely continue. It is an ongoing topic in facilities design.

Synchronization

If the team cannot work all the time in one room, perhaps they can at least be gathered periodically. There is a broad spectrum of synchronization approaches:

All of them are essentially similar in approach and assumption: build a shared understanding of the work, objectives, or mission among smaller or larger sections of the organization, through limited-time face to face interaction, often on a defined time interval.

Cadenced approaches. When a synchronization activity occurs on a timed interval, this can be called a cadence. Sometimes, cadences are layered; for example, a daily standup, a weekly review, and a monthly Scrum of Scrums. Reinertsen calls this harmonic cadencing [220 pp. 190-191]. Harmonic cadencing (monthly, quarterly, and annual financial reporting) has been used in financial management for a long time.

Boundary spanning

The philosophy is that you push the power of decision making out to the periphery and away from the center. You give people the room to adopt, based on their experiences and expertise. All you ask is that they talk to one another and take responsibility. That is what works.

The Checklist Manifesto

Examples of boundary-spanning liaison and coordination structures include:

-

Shared team members

-

Integration teams

-

Coordination roles

-

Communities of practice

-

Scrum of scrums

-

Submittal schedules

-

API standards

-

RACI/ECI decision rights

Shared team members are suggested when two teams have a persistent interface requiring focus and ownership. When a product has multiple interfaces that emerge as a problem requiring focus, an integration team may be called for. Coordination roles can include project and program managers, release train conductors, and the like. Communities of practice will be introduced in Chapter 9 when we discuss the Spotify model. Considered here, they may also play a coordination role as well as a practice development/maturity role.

Finally, the idea of a Scrum of Scrums is essentially a representative or delegated model, in which each Scrum team sends one individual to a periodic coordination meeting where matters of cross-team concern can be discussed and decisions made [67], Chapter 17.

Cohn cautions: “A scrum of scrums meeting will feel nothing like a daily scrum despite the similarities in names. The daily scrum is a synchronization meeting: individual team members come together to communicate about their work and synchronize their efforts. The scrum of scrums, on the other hand, is a problem-solving meeting and will not have the same quick, get-in-get-out tone of a daily scrum [67 p. 342].”

Another technique mentioned in The Checklist Manifesto [105] is the submittal schedule. Some work, while detailed, can be planned to a high degree of detail (i.e. the “checklists” of the title). However, emergent complexity requires a different approach — no checklist can anticipate all eventualities. In order to handle all the emergent complexity, the coordination focus must shift to structuring the right communications. In examining modern construction industry techniques, Gawande noted the concept of the “submittal schedule,” which “didn’t specify construction tasks; it specified communication tasks” (p. 65, emphasis supplied). With the submittal schedule, the project manager tracks that the right people are talking to each other to resolve problems — a key change in focus from activity-centric approaches.

We have previously discussed APIs in terms of Amazon's product strategy. They are also important as a product scales into multiple components and features; API standards can be seen as a boundary-spanning mechanism.

The above discussion is by no means exhaustive. A wealth of additional techniques relevant for digital professionals is to be found in [168, 67]. New techniques are continually emerging from the front lines of the digital profession; the interested student should consider attending industry conferences such as those offered by the Agile Alliance.

In general, the above approaches imply synchronized meetings and face to face interactions. When the boundary-spanning approach is based on artifacts (often a requirement for larger, decentralized enterprises), we move into the realms of process and project management. Approaches based on routing artifacts into queues often receive criticism for introducing too much latency into the product development process. When artifacts such as work orders and tickets are routed for action by independent teams, prioritization may be arbitrary (not based on business value, e.g., cost of delay). Sometimes the work must flow through multiple queues in an uncoordinated way. Such approaches can add dangerous latency to high-value processes, as we warned in Chapter 5. We will look in more detail at process management in a future section.

7.2.4. Coordination effectiveness

Diane Strode and her colleagues propose that coordination effectiveness can be understood as the following taxonomy:

-

Implicit

-

Knowing why (shared goal)

-

Know what is going on and when

-

Know what to do and when

-

Know who is doing what

-

Know who knows what

-

-

Explicit

-

Right place

-

Right thing

-

Right time

-

Coordinated execution means that teams have a solid common ground of what they are doing and why, who is doing it, when to do it, and where to go for information. They also have the material outcomes of the right people being in the right place doing the right thing at the right time. These coordination objectives must be achieved with a minimum of waste, and with a speed supporting an OODA loop tighter than the competition’s. Indeed, this is a tall order!

7.3. Coordination, execution, and the delivery models

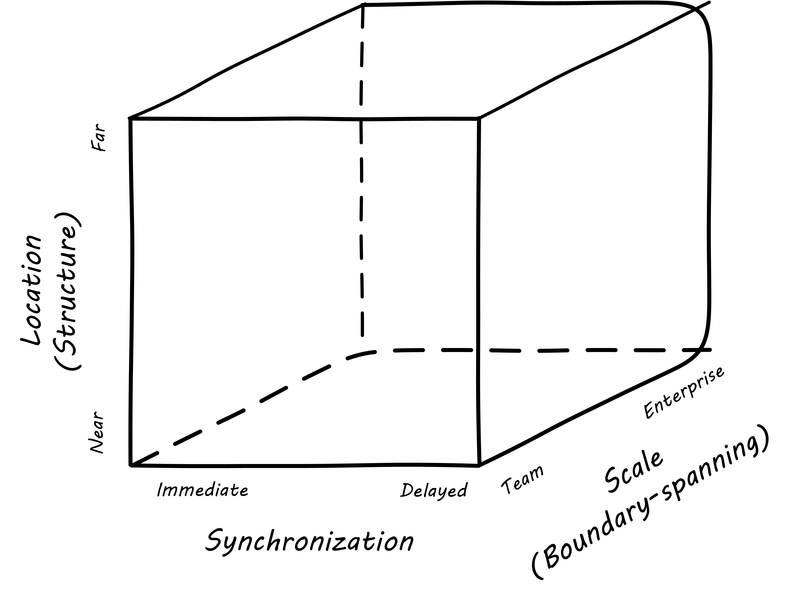

If we take the strategies proposed by Strode et al. and think of them as three, orthogonal dimensions, we can derive another useful 3-dimensional figure (Cube derived from Strode):

-

Projects often are used to create and deploy processes. A large system implementation (e.g.,of a Enterprise Resource Planning module such as Human Resource Management) will often be responsible for process implementation including training.

-

As environments mature, product and/or project teams require process support.

-

At the origin point, we have practices like face to face meetings at at various scales.

-

Geographically distant, immediate coordination is achieved with messaging and other forms of telecommunications.

-

Co-located but ansynchronous coordination is achieved through shared artifacts like Kanban boards.

-

Distant and asynchronous coordination again requires some kind of telecommunications

The Z-axis is particularly challenging, as it represents scaling from a single to multiple and increasingly organizationally distant teams. Where a single team may be able to maintain a good sense of common ground even when geographically distant, or working asynchronously, adding the third dimension of organizational boundaries is where things get hard. Larger-scale coordination strategies include:

-

Operational digital processes (Chapter 6)

-

Change management

-

Incident management

-

Request management

-

Problem management

-

Release management

-

-

Specified decision rights

-

Projects and project managers (Chapter 8)

-

Shared services and expertise (Chapter 8)

-

Organization structures (Chapter 9)

-

Cultural norms (Chapter 9)

-

Architecture standards (Chapters 11 and 12)

All of these coping mechanisms risk compromising to some degree the effectiveness of co-located, cross-functional teams. Remember that the high-performing product team is likely the highest-value resource known to the modern organization. Protecting the value of this resource is critical as the organization scales up. The challenge is that models for coordinating and sustaining complex digital services are not well understood. IT organizations have tended to fall back on older supply-chain thinking, with waterfall-derived ideas that work can be sequenced and routed between teams of specialists. (More on this to come in Chapter 9).

|

Note

|

We recommend you review the definitions of the “3 P’s": product, project, and process management. |

7.3.1. Product management release trains

Where project and process management are explicitly coordination-oriented, product management is broader and focused on outcomes. As noted previously, it might use either a project or a process management to achieve its outcomes, or it might not.

Release management was introduced in Part I, and has remained a key concept we’ll return to now. Release management is a common coordination mechanism in product management, even in environments that don’t otherwise emphasize processes or projects. At scale, the concept of a “release train” is seen. The Scaled Agile Framework considers it the “primary value delivery construct” [234].

The train is a cadenced synchronization strategy. It “departs the station” on a reliable schedule. As with Scrum, date and quality are fixed, while the scope is variable. The Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe) emphasizes that “being on the train” in general is a full-time responsibility, so the train is also a temporary organizational or programmatic concept. The release train “engineer” or similar role is an example of the coordinator role seen in the Strode coordination tools and techniques matrix.

The release train is a useful concept for coordinating large, multi-team efforts, and is applicable in environments that have not fully adopted Agile approaches. As author Joanna Rothman notes, “You can de-scope features from a particular train, but you can never allow a train to be late. That helps the project team focus on delivering value and helps your customer become accustomed to taking the product on a more frequent basis” [229].

7.3.2. Project management as coordination

|

Note

|

We’ll talk about project management as an investment strategy in the next chapter. In this chapter, we look at it as a coordination strategy. If you are completely unfamiliar with project management, see the brief introduction in the appendix and the PMBOK summary. |

Project management adds concerns of task ordering and resource management, for efforts typically executed on a one-time basis. Project management groups together a number of helpful coordination tools which is why it is widely used. These tools include:

-

Sequencing tasks

-

Managing task dependencies

-

Managing resource dependencies of tasks

-

Managing overall risk of interrelated tasks

-

Planning complex activity flows to complete at a given time

However, project management also has a number of issues:

-

Projects are by definition temporary, while products may last as long as there is market demand.

-

Project management methodology, with its emphasis on predictability, scope management, and change control often conflicts with the product management objective of discovering information (see the discussion of Lean Product Development).

(But not all large management activities involve the creation of new information! Consider the previous example of upgrading the RAM in 80,000 POS terminals in 2000 stores).

The project paradigm has a benefit in its explicit limitation of time and money, and the sense of urgency this creates. In general, scope, execution, limited resources, deadlines, and dependencies exist throughout the digital business. A product manager with no understanding of these issues, or tools to deal with them, will likely fail. Product managers should, therefore, be familiar with the basic concepts of project management. However, the way in which project management is implemented, the degree of formality, will vary according to need.

A project manager may still be required, to facilitate discussions, record decisions, and keep the team on track to its stated direction and commitments. Regardless of whether the team considers itself “Agile,” people are sometimes bad at taking notes or being consistent in their usage of tools such as Kanban boards and standups.

It is also useful to have a third party who is knowledgeable about the product and its development, yet has some emotional distance from its success. This can be a difficult balance to strike, but the existence of the role of Scrum coach is indicative of its importance.

We will take another look at project management, as an investment management approach, in Chapter 8.

7.3.3. Decision rights

There are two ways of communicating boundaries inside the organization. Unfortunately, the most common approach is trial and error. Some people refer to this as discovering the location of the invisible electric fences. There is a better approach for setting boundaries. It consists of clarifying expectations for the entire team regarding their authority to make decisions. This is done by making a list of specific decisions and discussing them with the functional managers and the team. A two-hour meeting early in the program can have enormous impact on clarifying intended operating practices to the team [219 pp. 106-108].

Managing the Design Factory

Approvals are a particular form of activity dependency, and since approvals tend to flow upwards in the organizational hierarchy to busy individuals, they can be a significant source of delay and as Reinertsen points out [219 p. 108], discovering “invisible electric fences” by trial and error is both slow and also reduces human initiative. One boundary spanning coordination artifact an organization can produce as a coordination response is a statement of decision rights, for example, a RACI analysis. RACI stands for

-

Responsible

-

Accountable (sometimes understood as Approves)

-

Consulted

-

Informed

A RACI analysis is often used when accountability must be defined for complex activities. It is used in process management, and also is seen in project management and general organizational structure.

| Team member | Product owner | Chief product owner | |

|---|---|---|---|

Change interface affecting two modules |

Responsible |

Accountable |

Informed |

Change interface affecting more than two modules |

Responsible |

Informed |

Accountable |

Hire new team member |

Consulted |

Responsible |

Accountable |

Some agile authors call for an “ECI” matrix, with the “E” standing for empowered, defined as both Accountable and Responsible.

7.3.4. Process management as coordination

We discussed the emergence of process management in Chapter 5, and in Chapter 6 the basic digital processes of Change, Incident, Problem, and Request management. You should also review the process modeling overview in the appendix.

As we saw in the Strode dependency taxonomy, waiting on a business process is a form of dependency. But business processes are more than just dependency sources and obstacles; they themselves are a form of coordination. In Strode’s terms, they are a boundary spanning activity. It is ironic that a coordination tool itself might be seen as a dependency and blockage to work; this shows at least the risk of assuming that all problems can or should be solved by tightly-specified business processes!

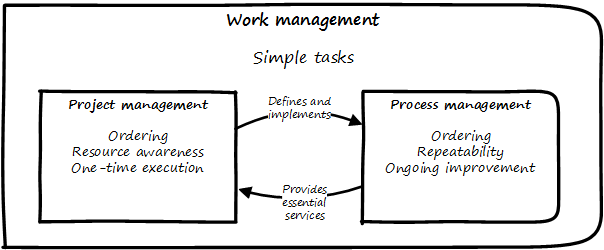

Like project management, process management is concerned with ordering, but less so with the resource load (more on this to come), and more with repeatability and ongoing improvement. The concept of process is often contrasted with that of function or organization. Process management’s goal is to drive repeatable results across organizational boundaries. As we know from our discussion of product management, developing new products is not a particularly repeatable process. The Agile movement arose as a reaction to mis-applied process concepts of "repeatability” in developing software. These concerns remain. However, this book covers more than development. We are interested in the spectrum of digital operations and effort that spans from the unique to the highly repeatable. There is an interesting middle ground, of processes that are at least semi-repeatable. Examples often found in the large digital organization include:

-

Assessing, approving, and completing changes

-

End user equipment provisioning

-

Resolving incidents and answering user inquiries

-

Troubleshooting problems

We will discuss a variety of such processes, and the pros and cons of formalizing them, in the Chapter 9 section on industry frameworks. In Chapter 10, we will discuss IT governance in depth. The concept of “control” is critical to IT governance, and processes often play an important role in terms of control.

Just as the traditional IT project is under pressure, there are similar challenges for the traditional IT process. DevOps and continuous delivery are eroding the need for formal change management. Consumerization is challenging traditional internal IT provisioning practices. And self-service help desks are eliminating some traditional support activities. Nevertheless, any rumors of an “end to process” are probably greatly exaggerated. Measurability remains a concern; the Lean philosophy underpinning much Agile thought emphasizes measurement. There will likely always be complex combinations of automated, semi-automated, and manual activity in digital organizations. Some of this activity will be repeatable enough that the “process” construct will be applied to it.

7.3.5. Projects and processes

Project management and process management interact in two primary ways as Process and project illustrates:

-

Projects often are used to create and deploy processes. A large system implementation (e.g.,of a Enterprise Resource Planning module such as Human Resource Management) will often be responsible for process implementation including training.

-

As environments mature, product and/or project teams require process support.

As Richardson notes in Project Management Theory and Practice, “there are many organizational processes that are needed to optimally support a successful project.” [221] For example, the project may require predictable contractor hiring, or infrastructure provisioning, or security reviews. The same is true for product teams that may not be using a “project” concept to manage their work. To the extent these are managed as repeatable, optimized processes, the risk is reduced. The trouble is when the processes require prioritization of resources to perform them. This can lead to long delays, as the teams performing the process may not have the information to make an informed prioritization decision. Many IT professionals will agree that the relationship between application and infrastructure teams has been contentious for decades because of just this issue. One response has been increasing automation of infrastructure service provisioning (private and external cloud).

7.4. Why process management?

Is a firm a collection of activities or a set of resources and capabilities? Clearly, a firm is both. But activities are what firms do, and they define the resources and capabilities that are relevant.

Competitive Advantage

Individuals and interactions over processes and tools.

Dictionary.com defines process as “a systematic series of actions directed to some end … a continuous action, operation, or series of changes taking place in a definite manner.” We saw the concept of “process” start to emerge in Chapter 5, as work become more specialized and repeatable and our card walls got more complicated.

We’ve discussed work management, which is an important precursor of process management. Work management is less formalized; a wide variety of activities are handled through flexible Kanban-style boards or “card walls” based on the simplest “process” of:

-

To do

-

Doing

-

Done

However, the simple card wall/Kanban board can easily become much more complex, with the addition of swimlanes and additional columns, including holding areas for blocked work. As we discussed in Chapter 5, when tasks become more routine, repeatable, and specialized, formal process management starts to emerge. Process management starts with the fundamental capability for coordinated work management, and refines it much further.

Process, in terms of “business process,” has been a topic of study and field for professional development for many years. Pioneering Business Process Management (BPM) authors such as Michael Hammer [115], and Geary Rummler [233] have had an immense impact on business operations, with concepts such as Hammer’s Business Process Re-engineering (BPR). BPR initiatives are intended to identify waste and streamline processes, eliminating steps that no longer add value. BPR efforts often require new or enhanced digital systems.

In the Lean world, value stream mapping represents a way of understanding the end to end flow of value, typically in a manufacturing or supply chain operational context [228]. Toyota considers a clear process vision, or “target condition,” to be the most fundamental objective for improving operations [227], Chapters 5 and 6. Designing processes, improving them, and using them to improve overall performance is an ongoing activity in most, if not all organizations.

In your company, work has been specializing. A simple card-based Kanban approach is no longer sufficient. You are finding that some work is repetitive, and you need to remember to do certain things in certain orders. For example, a new Human Resources (HR) manager was hired and decided that a sticky note of “hire someone new for us” was not sufficient. As she pointed out to the team, hiring employees was a regulated activity, with legal liability, requiring confidentiality, that needed to follow a defined sequence of tasks:

-

Establishing the need and purpose for the position

-

Soliciting candidates

-

Filtering the candidates

-

Selecting a final choice

-

Registering that new employee in the payroll system

-

Getting the new employee set up with benefits providers (insurance, retirement, etc.).

-

Getting the new employee working space, equipment, and access to systems

-

Training the new employee in organizational policies, as well as any position-specific orientation

The sales, marketing, and finance teams have similarly been developing ordered lists of tasks that are consistently executed as end-to-end sequences. And even in the core digital development and operations teams, they are finding that some tasks are repetitive and need documentation so they are performed consistently.

Your entire digital product pipeline may be called a “process.” From initial feature idea through production, you seek a consistent means for identifying and implementing valuable functionality. Sometimes this work requires intensive, iterative collaboration and is unpredictable (e.g.,developing a user interface); sometimes, the work is more repeatable (e.g.,packaging and releasing tested functionality).

You’re hiring more specialized people with specialized backgrounds. Many of them enter your organization and immediately ask process questions:

-

What’s your Security process?

-

What’s your Architecture process?

-

What’s your Portfolio process?

You’ve not had these conversations before. What do they mean by these different “processes?” They seem to have some expectation based on their previous employment, and if you say “we don’t have one” they tend to be confused. You’re becoming concerned that your company may be running some risk, although you also are wary that “process” might mean slowing things down, and you can’t afford that.

However, some team members are cautious of the word “process." The term "process police” comes up in an unhappy way.

“Are we going to have auditors tracking whether we filled out all our forms correctly? ” one asks.

“We used to get these 'process consultants' in at my old company, and they would leave piles of 3 ring binders on the shelf that no one ever looked at,” another person says.

“I can’t write code according to someone’s recipe! ” a third says with some passion, and to general agreement from the developers in the room.

The irony is that digital products are based on process automation. The idea that certain tasks can be done repeatably and at scale through digitization is fundamental to all use of computers. The digital service is fundamentally an automated process, one that can be intricate and complicated. That’s what computers do. But, process management also spans human activities, and that’s where things get more complex.

Processes are how we ensure consistency, repeatability, and quality. You get expected treatment at banks, coffee shops, and dentists because they follow processes. IT systems often enable processes – a mortgage origination system is based on IT software that enforces a consistent process. IT management itself follows certain processes, for all the same reasons as above.

However, processes can cause problems. Like project management, the practice of process management is under scrutiny in the new Lean and Agile-influenced digital world. Processes imply queues, and in digital and other product development-based organizations, this means invisible work in process. For every employee you hire who expects you to have processes, another will have bad process experiences at previous employers. Nevertheless, process remains an important tool in your toolkit for organization design.

Process is a broad concept used throughout business operations. The coverage here is primarily about process as applied to the digital organization. There is a bit of a recursive paradox here; in part, we are talking about the process by which business processes are analyzed and sometimes automated. By definition, this overall “process” (you could call it a meta-process) cannot be made too prescriptive or predictable.

The concept of “process” is important and will persist through digital transformation. We need a robust set of tools to discuss it. This chapter will break the problem into a lifecycle of:

-

Process conception

-

Process content

-

Process execution

-

Process improvement

Although we don’t preface these topics with “Agile” or “Lean,” bringing these together with related perspectives is the intent of this chapter.

7.4.1. Process conception

“Many companies have at least one dysfunctional area. This may be the “furniture police” who won’t let programmers rearrange furniture to facilitate pair programming. Or it may be a purchasing group that takes six weeks to process a standard software order. In any event, these types of insanity get in the way of successful projects.”

Succeeding with Agile: Software Development Using Scrum

Processes can generate various emotional reactions:

“Dysfunctional! Insanity!” (as above)

“Follow the process!”

“What bureaucracy!”

“Don’t create the 'Process Police'!”

“I am an IT Service Management professional. I believe in the ITIL framework!”

“I don’t write code on an assembly line!”

Such reactions are commonplace in social media (and even well-regarded professional books), but we need a more objective and rational approach to understand the pros and cons of processes. We have seen a number of neutral concepts towards this end from authors such as Don Reinertsen and Diane Strode:

A process is a technique, a tool, and no technique should be implemented without a thorough understanding of the organizational context. Nor should any technique be implemented without rigorous, disciplined follow-up as to its real effects, both direct and indirect. Many of the issues with process come from a cultural failure to seek an understanding of the organization needs in objective terms such as these. We’ll think about this cultural failure more in the Chapter 9 discussion of Toyota Kata.

A skeptical and self-critical, “go and see” approach is, therefore, essential. Too often, processes are instituted in reaction to the last crisis, imposed top down, and rarely evaluated for effectiveness. Allowing affected parties to lead a process re-design is a core Lean principle (kaizen). On the other hand, uncoordinated local control of processes can also have destructive effects as discussed below.

7.4.2. Process execution

Since our initial discussions in Chapter 5 on Work Management, we find ourselves returning full circle. Despite the various ways in which work is conceived, funded, and formulated, at the end “it’s all just work.” The digital organization must retain a concern for the “human resources” (that is, people) who find themselves at the mercy of:

-

Project fractional allocations driving multi-tasking and context-switching

-

Processes imposed top down with little demand analysis or evaluation of benefits

-

Myriad demands that, although critical, do not seem to fit into either of the first two categories

The Lean movement manages through minimizing waste and over-processing. This means both removing un-necessary steps from processes, AND eliminating un-necessary processes completely when required. Correspondingly, the processes that remain should have high levels of visibility. They should be taken with the utmost seriousness, and their status should be central to most people’s awareness. (This is the purpose of Andon.

From workflow tools to collaboration and digital exhaust. One reason process tends to generate friction and be unpopular is the poor usability of workflow tools. Older tools tend to present myriads of data fields to the user and expect a high degree of training. Each state change in the process is supposed to be logged and tracked by having someone sign in to the tool and update status manually.

By contrast, modern workflow approaches take full advantage of mobile platforms and integration with technology like chat rooms and ChatOps. Mobile development imposes higher standards for user experience (UX) design, which makes tracking workflow somewhat easier. Integrated software pipelines that integrate application lifecycle management and/or project management with source control and build management are increasingly gaining favor. For example:

-

A user logs a new feature request in the Application Lifecycle Management (ALM) tool

-

When the request is assigned to a developer, the tool automatically creates a feature branch in the source control system for the developer to work on

-

The developer writes tests and associated code and merges changes back to the central repository once tests are passed successfully

-

The system automatically runs build tests

-

The ALM tool is automatically updated accordingly with completion if all tests pass

See also the previous discussion of ChatOps, which similarly combines communication and execution in a low-friction manner, while providing rich digital exhaust as an audit trail.

In general, the idea is that we can understand digital processes not through painful manual status updates, but rather through their digital exhaust — the data byproducts of people performing the value-add day-to-day work, at speed and with the flow instead of constant delays for approvals and status updates.

7.4.3. Measuring process

One of the most important reasons for repeatable processes is so that they can be measured and understood. Repeatable processes are measured in terms of:

-

Speed

-

Effort

-

Quality

-

Variation

-

Outcomes

at the most general level, and of course, all of those measurements must be defined much more specifically depending on the process. Operations (often in the form of business processes) generate data, and data can be aggregated and reported on. Such reporting serves as a form of feedback for management and even governance. Examples of metrics might include:

-

Quarterly sales as a dollar amount

-

Percentage of time a service or system is available

-

Number of successful releases or pushes of code (new functionality)

Measurement is an essential aspect of process management but must be carefully designed. Measuring process can have unforeseen results. Process participants will behave according to how the process is measured. If a help desk operator is measured and rated on how many calls they process an hour, the quality of those interactions may suffer. It is critical that any process “key performance indicator” be understood in terms of the highest possible business objectives. Is the objective truly to process as many calls as possible? Or is it to satisfy the customer so they need not turn to other channels to get their answers?

A variety of terms and practices exist in process metrics and measurement, such as:

-

The Balanced Scorecard

-

The concept of a metrics hierarchy

-

Leading versus lagging indicators

The Balanced Scorecard is a commonly-seen approach for measuring and managing organizations. First proposed by Kaplan and Norton [148] in the Harvard Business Review, the Balanced Scorecard groups metrics into the following subject areas:

-

Financial

-

Customer

-

Internal business processes

-

Learning and growth

Metrics can be seen as “lower” versus “higher” level. For example, the metrics from a particular product might be aggregated into a hierarchy with the metrics from all products, to provide an overall metric of product success. Some metrics are perceived to be of particular importance for business processes, and thus may be termed Key Performance Indicators. Metrics can indicate past performance (lagging), or predict future performance (leading).

7.4.4. Process improvement

There tended to be no big picture waiting to be revealed . . . there was only process kaizen . . . focused on isolated individual steps. . . . We coined the term “kamikaze kaizen” . . . to describe the likely result: lots of commotion, many isolated victories . . . [and] loss of the war when no sustainable benefits reached the customer or the bottom line.

and Jones

Once processes are measured, the natural desire is to use the measurements to improve them. We discussed Business Process Re-engineering above. In Lean, there are the concepts of kaizen and kaikaku. Kaizen is an incremental process change; kaikaku is a more radical, abrupt shift in the overall process.

There are many ways that process improvement can go wrong.

-

Not basing process improvement in an empirical understanding of the situation

-

Process improvement activities that do not involve those affected

-

Not treating process activities as demand in and of themselves

-

Uncoordinated improvement activities, far from the bottom line

The solutions are to be found largely within Lean theory.

-

Understand the facts of the process; do not pretend to understand based on remote reports. “Go and see,” in other words.

-

Respect people, and understand that best understanding of the situation is held by those closest to it.

-

Make time and resources available for improvement activities. For example, assign them a Problem ticket and ensure there are resources specifically tasked with working it, who are given relief from other duties.

-

Periodically review improvement activities as part of the overall portfolio. You are placing “bets” on them just as with new features. Do they merit your investment?

In the next section, we’ll look at some of the history and theory behind continuous improvement.

7.4.5. The disadvantages of process

Netflix CTO Reed Hastings, in an influential public presentation "Netflix Culture: Freedom and Responsibility," presents a skeptical attitude towards process. In his view, process emerges as a result of an organization’s talent pool becoming diluted with growth, while at the same time its operations become more complex.

Hastings observes that companies that become overly process-focused can reap great rewards as long as their market stays stable. However, when markets change, they also can be fatally slow to adapt.

Netflix’s strategy is to focus on hiring the highest-performance employees and keeping processes minimal. They admit that their industry (minimally-regulated, creative, non-life-critical) is well suited to this approach [120].

The pitfall of process “silos”

One organization enthusiastically embraced process improvement, with good reason: customers, suppliers, and employees found the company’s processes slow, inconsistent, and error prone. Unfortunately, they were so enthusiastic that each team defined the work of their small group or department as a complete process. Of course, each of these was, in fact, the contribution of a specialized functional group to some larger, but unidentified, processes. Each of these “processes” was “improved” independently, and you can guess what happened.

Within the boundaries of each process, improvements were implemented that made work more efficient from the perspective of the performer. However, these mini-processes were efficient largely because they had front-end constraints that made work easier for the performer but imposed a burden on the customer or the preceding process. The attendant delay and effort meant that the true business processes behaved even more poorly than they had before. This is a common outcome when processes are defined too “small.” Moral: Don’t confuse subprocesses or activities with business processes.

Workflow Modeling

The above quote (from [245]) well illustrates the dangers of combining local optimization and process management. Many current authors speak highly of self-organizing teams, but self-organizing teams may seek to optimize locally. Process management was originally intended to overcome this problem, but modeling techniques can be applied at various levels, including within specific departments. This is where enterprise Business Architecture can assist, by identifying these longer, end to end flows of value and highlighting the handoff areas, so that the process benefits the larger objective.

Process proliferation

Another pitfall we cover here is that of process proliferation. Process is a powerful tool. Ultimately it is how value is delivered. However, too many processes can have negative results on an organization. One thing often overlooked in process management and process frameworks is any attention to the resource impacts of the process. This is a primary difference between project and process management; in process management (both theory and frameworks), resource availability is in general assumed.

More advanced forms of process modeling and simulation (for example “discrete event simulation”) can provide insight into the resource demands for processes. However, such techniques 1) require specialized tooling and 2) are not part of the typical business process management practitioner’s skillset.

Many enterprise environments have multiple cross-functional processes such as:

-

Service requests

-

Compliance certifications

-

Asset validations

-

Provisioning requests

-

Capacity assessments

-

Change approvals

-

Training obligations

-

Performance assessments

-

Audit responses

-

Expense reporting

-

Travel approvals

These processes sometimes seem to be implemented on the assumption that enterprises can always accommodate another process. The result can be a dramatic overburden for digital staff in complex environments. A frequently-discussed responsibility of Scrum masters and product owners is to “run interference” and keep such enterprise processes from eroding team cohesion and effectivness. It is, therefore, advisable to at least keep an inventory of processes that may impose demand on staff, and understand both the aggregate demand as well as the degree of multi-tasking and context-switching that may result (as discussed in Chapter 5). Thorough automation of all processes to the maximum extent possible can also drive value, to reduce latency, load, and multi-tasking.

7.5. Process control and continuous improvement

a process can still be controlled even if it can’t be defined.

preface to Agile Software Development with Scrum

|

Note

|

This is more advanced material, but critical to understanding the mathematical basis of Agile methods. |

Process management, like project management, is a discipline unto itself and one of the most powerful tools in your toolbox. You start to realize there is a process by which process itself is managed — the process of continuous improvement. You remain concerned that work continues to flow well, that you don’t take on too much work in process, and that people are not overloaded and multi-tasking.

In this chapter section, we take a deeper look at the concept of process and how processes are managed and controlled. In particular, we will explore the concept of continuous (or continual) improvement and its rich history and complex relationship to Agile.

You are now at a stage in your company’s evolution, or your career, where an understanding of continuous improvement is helpful. Without this, you will increasingly find you don’t understand the language and motivations of leaders in your organization, especially those with business degrees or background.

|

Note

|

There is a debate over whether to use the term “continuous” or “continual” improvement. We will use “continuous” here as it is the more commonly seen. Advocates of “continual” argue it is the more grammatically correct. |

The scope of the word “process” is immense. Examples include:

-

The end to end flow of chemicals through a refinery

-

The set of activities across a manufacturing assembly line, resulting in a product for sale

-

The steps expected of a customer service representative in handling an inquiry

-

The steps followed in troubleshooting a software-based system

-

The general steps followed in creating and executing a project

-

The overall flow of work in software development, from idea to operation

This breadth of usage requires us to be specific in any discussion of the word “process.” In particular, we need to be careful in understanding the concepts of efficiency, variation, and effectiveness. These concepts lie at the heart of understanding process control and improvement and how to correctly apply it in the digital economy.

Companies institute processes because it has been long understood that repetitive activities can be optimized when they are better understood, and if they are optimized, they are more likely to be economical and even profitable. We have emphasized throughout this book that the process by which complex systems are created is not repetitive. Such creation is a process of product development, not production. And yet, the entire digital organization covers a broad spectrum of process possibilities, from the repetitive to the unique. You need to be able to identify what kind of process you are dealing with, and to choose the right techniques to manage it. (For example, the employee provisioning process flow that is shown in the appendix is simple and prescriptive. Measuring its efficiency and variability would be possible, and perhaps useful).

There are many aspects of the movement known as “continuous improvement” that we won’t cover in this brief section. Some of them (systems thinking, culture, and others) are covered elsewhere in this book. This book is based in part on Lean and Agile premises, and continuous improvement is one of the major influences on Lean and Agile, so in some ways, we come full circle. Here, we are focusing on continuous improvement in the context of processes and process improvement. We’ll therefore scope this to a few concerns: efficiency, variation, effectiveness, and process control.

7.5.1. History of continuous improvement

|

Note

|

History is important. You may think your career is far removed from the early days of the Industrial Revolution, but the influence of early management thinkers such as Frederick Taylor defines our world to a degree you probably don’t yet realize. You need to be able to recognize when his ideas are being applied, especially if they are being applied inappropriately (as can easily happen in modern digital organizations). |

The history of continuous improvement is intertwined with the history of 20th century business itself. Before the Industrial Revolution, goods and services were produced primarily by local farmers, artisans, and merchants. Techniques were jealously guarded, not shared. A given blacksmith might have two or three workers, who might all forge a pan or a sword in a different way. The term “productivity” itself was unknown.

Then the Industrial Revolution happened.

As steam and electric power increased the productivity of industry, requiring greater sums of capital to fund, a search for improvements began. Blacksmith shops (and other craft producers such as grain millers and weavers) began to consolidate into larger organizations, and technology became more complex and dangerous. It started to become clear that allowing each worker to perform the work as they preferred was not feasible.

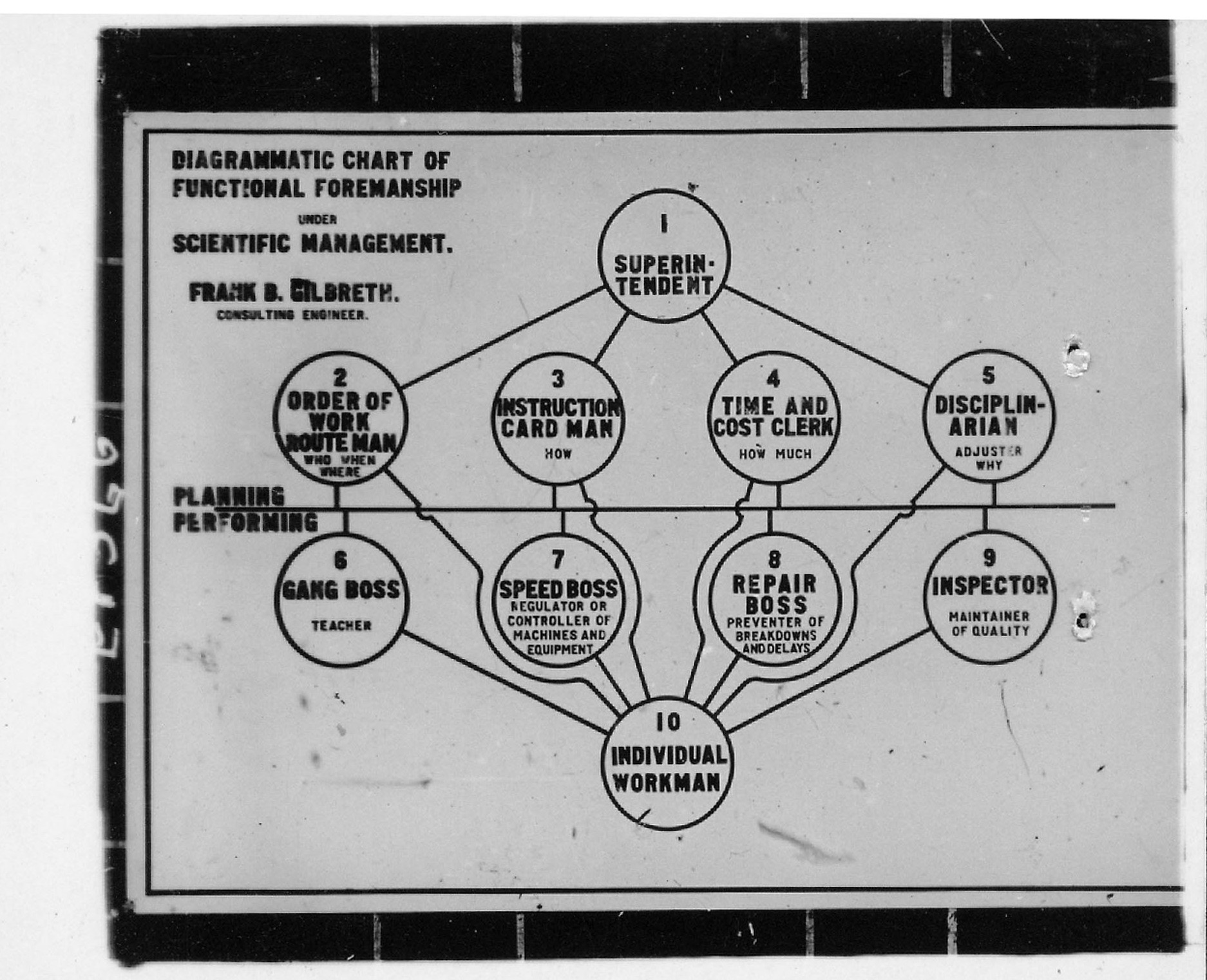

Enter the scientific method. Thinkers such as Frederick Taylor and Frank and Lillian Gilbreth (of Cheaper by the Dozen fame,) started applying careful techniques of measurement and comparison, in search of the “one best way” to dig ditches, forge implements, or assemble vehicles. Organizations became much more specialized and hierarchical, as shown in the accompanying early organization chart by Gilbreth (see Gilbreth “scientific management” organization [1]). An entire profession of industrial engineering was established, along with the formal study of business management itself.

7.5.2. Frederick Taylor and efficiency

Frederick Taylor (1856-1915) was a mechanical engineer and one of the first industrial engineers. In 1911, he wrote Principles of Scientific Management. One of Taylor’s primary contributions to management thinking was a systematic approach to efficiency. To understand this, let’s consider some fundamentals.

Human beings engage in repetitive activities. These activities consume inputs and produce outputs. It is often possible to compare the outputs against the inputs, numerically, and understand how “productive” the process is. For example, suppose you have two factories producing identical kitchen utensils (such as pizza cutters). If one factory can produce 50,000 pizza cutters for $2,000, while the other requires $5,000, the first factory is more productive.

Assume for a moment that the workers are all earning the same across each factory, and that both factories get the same prices on raw materials. There is possibly a “process” problem. The first factory is more efficient than the second; it can produce more, given the same set of inputs. Why?

There are many possible reasons. Perhaps the second factory is poorly laid out, and the work in progress must be moved too many times in order for workers to perform their tasks. Perhaps the workers are using tools that require more manual steps. Understanding the differences between the two factories, and recommending the “best way,” is what Taylor pioneered, and what industrial engineers do to this day.

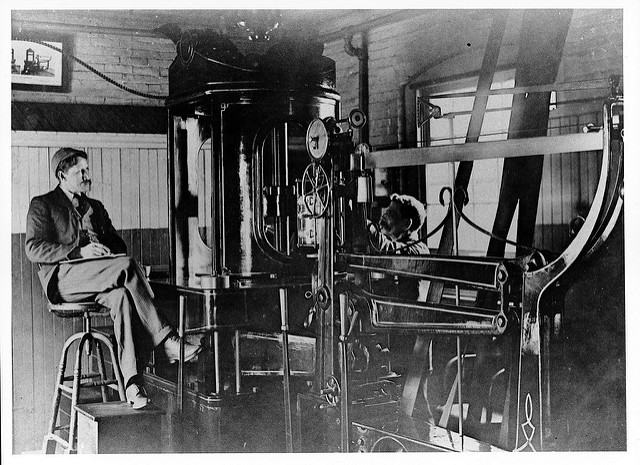

As Peter Drucker, one of the most influential management thinkers, says of Frederick Taylor:

The history of industrial engineering is often controversial, however. Hard-won skills were analyzed and stripped from traditional craftspeople by industrial engineers with clipboards (see An industrial engineer observing a worker [2]), who now would determine the “one best way.” Workers were increasingly treated as disposable. Work was reduced to its smallest components of a repeatable movement, to be performed on the assembly line, hour after hour, day after day until the industrial engineers developed a new assembly line. Taylor was known for his contempt for the workers, and his methods were used to increase work burdens sometimes to inhuman levels. Finally, some kinds of work simply can’t be broken into constituent tasks. High performing, collaborative, problem-solving teams do not use Taylorist principles, in general. Eventually, the term "Taylorism” was coined, and today is often used more as a criticism than a compliment.

7.5.3. W.E. Deming and variation

The quest for effiency leads to the long-standing management interest in variability and variation. What do we mean by this?

If you expect a process to take 5 days, what do you make of occurrences when it takes 7 days? 4 days? If you expect a manufacturing process to yield 98% usable product, what do you do when it falls to 97%? 92%? In highly repeatable manufacturing processes, statistical techniques can be applied. Analyzing such “variation” has been a part of management for decades, and is an important part of disciplines such as Six Sigma. This is why Six Sigma is of such interest to manufacturing firms.

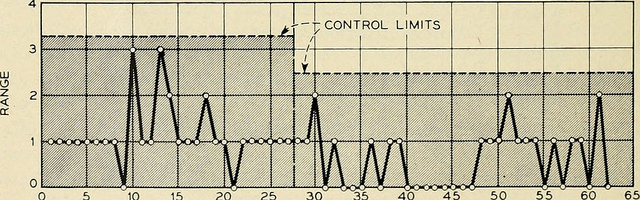

W. Edwards Deming (1900-1993) is noted for (among many other things) his understanding of variation and organizational responses to it. Understanding variation is one of the major parts of his “System of Profound Knowledge.” He emphasizes the need to distinguish special causes from common causes of variation; special causes are those requiring management attention.

Deming, in particular, was an advocate of the control chart, a technique developed by Walter Shewhart, to understand whether a process was within statistical control (see Process control chart [3]).

However, using techniques of this nature makes certain critical assumptions about the nature of the process. Understanding variation and when to manage it requires care. These techniques were defined to understand physical processes that in general follow normal distributions.

For example, let’s say you are working at a large manufacturer, in their IT organization, and you see the metric of "variance from project plan.” The idea is that your actual project time, scope and resources should be the same, or close to, what you planned. In practice, this tends to become a discussion about time, as resources and scope are often fixed.

The assumption is that, for your project tasks, you should be able to estimate to a meaningful degree of accuracy. Your estimates are equally likely to be too low, or too high. Furthermore, it should be somehow possible to improve the accuracy of your estimates. Your annual review depends on this, in fact.

The problem is that neither of these is true. Despite heroic efforts, you cannot improve your estimation. In process control jargon, there are too many causes of variation for “best practices” to emerge. Project tasks remain unpredictable, and the variability does not follow a normal distribution. Very few tasks get finished earlier than you estimated, and there is a long tail to the right, of tasks that take 2x, 3x or 10x longer than estimated.

|

Important

|

Learning some statistics is essential if you want to progress in your career. This section assumes you are comfortable with the concept of a “distribution” and in particular what the “normal distribution” is. |

In general, applying statistical process control to variable, creative product development processes is inappropriate. For software development, Steven Kan states: “Many assumptions that underlie control charts are not being met in software data. Perhaps the most critical one is that data variation is from homogeneous sources of variation.” That is, the causes of variation are knowable and can be addressed. This is in general not true of development work. [146]

Deming (along with Juran) is also known for “continuous improvement” as a cycle, e.g., "Plan/Do/Check/Act” or "Define/Measure/Analyze/Implement/Control.” Such cycles are akin to the scientific method, as they essentially engage in the ongoing development and testing of hypotheses, and the implementation of validated learning. We touch on similar cycles in our discussions of Lean Startup, OODA, and Toyota Kata.

7.5.4. Lean product development and cost of delay

the purpose of controlling the process must be to influence economic outcomes. There is no other reason to be interested in process control.

Managing the Design Factory

Discussions of efficiency usually focus on productivity that is predicated on a certain set of inputs. Time can be one of those inputs. Everything else being equal, a company that can produce the pizza cutters more quickly is also viewed as more efficient. Customers may pay a premium for early delivery, and may penalize late delivery; such charges typically would be some percentage (say plus or minus 20%) of the final price of the finished goods.

However, the question of time becomes a game-changer in the “process” of new product development. As we have discussed previously, starting with a series of influential articles in the early 1980s, Don Reinertsen developed the idea of cost of delay for product development [219].

Where the cost of a delayed product shipment might be some percentage, the cost of delay for a delayed product could be much more substantial. For example, if a new product launch misses a key trade show where competitors will be presenting similar innovations, the cost to the company might be millions of dollars of lost revenue or more — many times the product development investment.

This is not a question of “efficiency;” of comparing inputs to outputs and looking for a few percentage points improvement. It is more a matter of effectiveness; of the company’s ability to execute on complex knowledge work.

7.5.5. Scrum and empirical process control

process theory experts . . . were amazed and appalled that my industry, systems development, was trying to do its work using a completely inappropriate process control model.

Agile Software Development with Scrum

Ken Schwaber, inventor of the Scrum methodology (along with Jeff Sutherland), like many other software engineers in the 1990s, experienced discomfort with the Deming-inspired process control approach promoted by major software contractors at the time. Mainstream software development processes sought to make software development predictable and repeatable in the sense of a defined process.

As Schwaber discusses [240 pp. 24-25] defined processes are completely understood, which is not the case with creative processes. Highly automated industrial processes run predictably, with consistent results. By contrast, complex processes that are not understood require an empirical model.

Empirical process control, in the Scrum sense, relies on frequent inspection and adaptation. After exposure to Dupont process theory experts who clarified the difference between defined and empirical process control, Schwaber went on to develop the influential Scrum methodology. As he notes:

During my visit to DuPont . . . I realized why [software development] was in such trouble and had such a poor reputation. We were wasting our time trying to control our work by thinking we had an assembly line when the only proper control was frequent and first-hand inspection, followed by immediate adjustments. [240 p. 25].

There’s little question that the idea of statistical process control for digital product development is thoroughly discredited. However, this is not only a textbook on digital product development (as a form of R&D). It covers all of traditional IT management, in its new guise of the digitally transformed organization. Development is only part of digital management.

7.6. Conclusion

In conclusion, we have considered:

-

Defining dependencies and coordination

-

Principles, and techniques of coordination

-

Coordination and delivery models

-

Process management

-

Background and history of continuous improvement

Coordination is a hard problem, and will only get more difficult as you scale up. However, it’s not magic and as a problem can be defined and analyzed. Process management is one response to the coordination problem (although its value extends beyond). Like any powerful tool, it has its dangers if misused. Be wary of claims of statistical process control in creative activities, and avoid burdensome process tracking and compliance approaches.

7.6.1. Discussion questions

-

Review The Secret to Amazons Success Internal APIs. Discuss in terms of solving coordination problems. Where does an API-based approach reach its limits as a coordination strategy?

-

Have you experienced a problem where an improved process would have helped? What about a problem where process seemed to be the cause of it?

-

What processes do you experience daily? Weekly?

-

Is some measurement of the process part of your experience? Think broadly.

-

Sometimes, organizations try to treat a complex process as defined, instead of managing it empirically. Sometimes, people react by calling this “Taylorism.” Why? Google and discuss.

7.6.2. Research & practice

-

Review the Strode dependency taxonomy and document examples. Present to your class for discussion.

-

Research BPMN notation and use it to document a process familiar to you.

-

Compare and contrast business process modeling with Lean value stream mapping.

-

Metrics are associated with most processes. Research well known industry processes that have standard metrics for comparison. For example, consider air travel and how airlines are compared regarding their flight operations processes.

-

Research process simulation and prepare a report. Optionally, compare process simulation with systems dynamics modeling.

-

We know that completely defined processes can be placed under statistical control, and that creative processes cannot be. What about processes falling between these two extremes, such as help desk call management? What does the research say about statistical control of such processes?

7.6.3. Further reading

Coordination is a general and abstract topic, and the research from [258, 155] is a good place to start. Practical discussions of coordination are found in [220] (especially Chapter 7-8) and also [219, 254]. From a software practitioner’s perspective see [67]. The history of Scrum is relevant, in particular, [240]. Critiques of statistical process control for software development are found in [30, 217].

The definitive BPM reference is [233]. Good practical applications are found in [44, 116, 245]. Lean theory is also essential, e.g., [286, 227].

Books

-

Geary Rummler and Alan Brache, Improving Performance: How to Manage the White Space in the Organization Chart

-

Paul Harmon, Business Process Change: A Guide for Business Managers and BPM and Six Sigma Professionals

Videos

Professional

Research

-

Gary Klein et al., Common Ground and Coordination in Joint Activity

-

Thomas Malone and Kevin Crowston, The Interdisciplinary Study of Coordination

-

Diane Strode and Sid Huff, A Taxonomy of Dependencies in Agile Software Development

-

Wil M.P. van der Aalst, Business Process Management: A Comprehensive Survey

Other

-

Martin Crane, BPM Lecture Notes