10. Governance, Risk, Security, and Compliance

10.1. Introduction

Operating at scale requires a different mindset. When you were starting out, the horizon seemed bounded only by your imagination, will, and talent. At enterprise scale, it’s a different world. You find yourself constrained by indifferent forces and hostile adversaries, some of them competing fairly, and others seeking to attack by any means. Whether or not you are a for-profit, publicly traded company, you are now large enough that audits are required; you also likely have directors of some nature. Like it or not, the concept of “controls” has entered your awareness.

As a team of teams, you needed to understand resource management, finance, the basics of multiple product management and coordination, and cross-functional processes. Now that you are an enterprise, you need also to consider questions of corporate governance. Your stakeholders have become more numerous, and their demands have multiplied, so the well-established practice of establishing a governing body has been applied.

Security threats increase proportionally to the company’s size. The talent and persistence of these adversaries are remarkable. Other challenging players are, on paper, “on the same side,” but auditors are never to be taken for granted. Why are they investigating IT systems? What are their motivations and responsibilities? Finally, what laws and regulations are relevant to IT?

|

Important

|

As with other chapters in the later part of this book, we are going to some degree introduce this topic “on its own terms.” We will then add additional context and critique in subsequent sections. |

More than any other chapter, the location of this chapter (and especially its Security subsection) in Section 4 draws attention. Again, any topic in any chapter may be a matter of concern at any stage in an organization’s evolution.

You’ve been doing security since your company started. Otherwise, you would not have gotten this big. But now, you have a Chief Information Security Officer, formal risk management processes, a standing director-level security steering committee, auditors, and compliance specialists. That kind of formalization does not usually happen until an organization grows to a certain size.

We needed the content in Section 3 to get this far. We had to understand our structure, how we were organizing our strategic investments, and how we were engaging in operational activities. In particular it’s difficult for an organization to govern itself without some ability to define and execute processes, as processes often support governance controls and security protocols.

This chapter covers “Governance, Risk, Security, and Compliance” because there are clear relationships between these concerns. They have important dimensions of independence as well. It is interesting that Shon Harris' popular Guide to the CISSP starts its discussion of security with a chapter titled “Information Security Governance and Risk Management.” Governance leads to a concern for risk, and security specializes in certain important classes of risk. Security requires grounding in governance and risk management.

Compliance is also related but again distinct, as the concern for adherence to laws and regulations, and secondarily internal policy.

10.1.1. Chapter 10 outline

-

Governance

-

Enablers

-

Risk management

-

Compliance

-

Assurance and audit

-

Security

-

Digital Governance

10.1.2. Chapter 10 learning objectives

-

Define governance versus management

-

Describe key objectives of governance according to major frameworks

-

Define risk management and its components

-

Describe and distinguish assurance and audit, and describe their importance to digital operations

-

Discuss digital security concerns and practices

-

Identify common regulatory compliance issues

-

Describe how governance is retaining its core concerns while evolving in light of digital transformation

-

Describe automation techniques relevant to supporting governance objectives throughout the digital delivery pipeline

10.2. Governance

10.2.1. What is governance?

The system by which organizations are directed and controlled.

The CObIT 5 framework makes a clear distinction between governance and management. These two disciplines encompass different types of activities, require different organisational structures and serve different purposes . . . In most enterprises, governance is the responsibility of the board of directors under the leadership of the chairperson [while] management is the responsibility of the executive management under the leadership of the CEO.

ISACA

To talk about governing digital or IT capabilities, we must talk about governance in general. Governance is a challenging and often misunderstood concept. First and foremost, it must be distinguished from “management.” This is not always easy but remains essential.

A governance example

Here is simple explanation of governance:

Suppose you own a small retail store. For years, you were the primary operator. You might have hired an occasional cashier, but that person had limited authority; they had the keys to the store and cash register, but not the safe combination, nor was their name on the bank account. They did not talk to your suppliers. They received an hourly wage, and you gave them direct and ongoing supervision. [1] In this case, you were a manager. Governance was not part of the relationship.

Now, you wish to go on an extended vacation — perhaps a cruise around the world, or a trek in the Himalayas. You need someone who can count the cash and deposit it, and place orders with and pay your suppliers. You need to hire a professional manager (see Someone to “mind the store” [2]).

They will likely draw a salary, perhaps some percentage of your proceeds, and you will not supervise them in detail as you did the cashier. Instead, you will set overall guidance and expectations for the results they produce. How do you do this? And perhaps even more importantly, how do you trust this person?

Now, you need governance.

As we see in the above quote, one of the most firmly reinforced concepts in the CObIT guidance (more on this and ISACA in the next section) is the need to distinguish governance from management. Governance is by definition a board-level concern. Management is the CEO’s concern. In this distinction, we can still see the shop owner and his or her delegate.

|

Important

|

There is too often a tendency to lump all of “management” in with governance. Sometimes it may be said that the VP of Sales, or Human Resources, “governs” their function, for example. While tempting to executives who want to elevate their status, this is not the intent of the term, as we will detail below. |

Some theory of goverance

In political science and economics, the need for governance is seen as an example of the principal-agent problem [87]. Our shopkeeper example illustrates this. The hired manager is the “agent,” acting on behalf of the shop owner, who is the “principal.”

In principal-agent theory, the agent may have different interests than the principal. The agent also has much more information (think of the manager running the shop day-to-day, versus the owner off climbing mountains). The agent is in a position to do economic harm to the principal; to shirk duty, to steal, to take kickbacks from suppliers. Mitigating such conflicts of interest is a part of governance.

In larger organizations (such as you are now), it’s not just a simple matter of one clear owner vesting power in one clear agent. The corporation may be publicly owned, or in the case of a non-profit, it may be seeking to represent a diffuse set of interests (e.g.,environmental issues). In such cases, a group of individuals (directors) is formed, often termed a “board,” with ultimate authority to speak for the organization.

The principal-agent problem can be seen at a smaller scale within the organization. Any manager encounters it to some degree, in specifying activities or outcomes for subordinates. But this does not mean that the manager is doing “governance,” as governance is by definition an organization-level concern.

The fundamental purpose of boards of directors and similar bodies is to take the side of the principal. This is easier said than done; boards can become overly close to an organization’s senior management — the senior managers are real people, while the “principal” may be an amorphous, distant body of shareholders and/or stakeholders.

Because governance is the principal’s concern, and because the directors represent the principal, governance, including IT governance, is a board-level concern.

There are various principles of corporate governance we will not go into here, such as shareholder rights, stakeholder interests, transparency, and so forth. References on these topics are included in the chapter conclusion (COSO and ISACA are good places to start). However, as we turn to our focus on digital and IT-related governance, there are a few final insights from the principal-agent theory that are helpful to understanding governance. Consider:

the heart of principal-agent theory is the trade-off between (a) the cost of measuring behavior and (b) the cost of measuring outcomes and transferring risk to the agent. [87]

What does this mean? Suppose the shopkeeper tells the manager, “I will pay you a salary of $50,000 while I am gone, assuming you can show me you have faithfully executed your daily duties.”

The daily duties are specified in a number of checklists, and the manager is expected to fill these out daily and weekly, and for certain tasks, provide evidence they were performed (e.g.,bank deposit slips, checks written to pay bills, photos of cleaning performed, etc.).. That is a behavior-driven approach to governance. The manager need not worry if business falls off; they will get their money. The owner has a higher-level of uncertainty; the manager might falsify records, or engage in poor customer service so that business is driven away. A fundamental conflict of interest is present; the owner wants their business sustained, while the manager just wants to put in the minimum effort to collect the $50,000. When agent responsibilities can be well specified in this manner, it is said they are highly programmable.

Now, consider the alternative. Instead of this very scripted set of expectations, the shopkeeper might tell the manager, “I will pay you 50% of the shop’s gross earnings, whether they may be. I’ll leave you to follow my processes however you see fit. I expect no customer or vendor complaints when I get back.”

In this case, the manager’s behavior is more aligned with the owner’s goals. If they serve customers well, they will likely earn more. There are any number of hard-to-specify behaviors (less programmable) that might be highly beneficial.

For example, suppose the store manager learns of an upcoming street festival, a new one that the owner did not know of or plan for. If the agent is managed in terms of their behavior, they may do nothing -— it’s just extra work. If they are measured in terms of their outcomes, however, they may well make the extra effort to order merchandise desirable to the street fair participants, and perhaps hire a temporary cashier to staff an outdoor booth, as this will boost store revenue and therefore their pay.

(Note that we have considered similar themes in our discussion of Agile and contract management, in terms of risk sharing).

In general, it may seem that an outcome-based relationship would always be preferable. There is, however, an important downside. It transfers risk to the agent (e.g.,the manager). And because the agent is assuming more risk, they will (in a fair market) demand more compensation. The owner may find themselves paying $60,000 for the manager’s services, for the same level of sales, because the manager also had to “price in” the possibility of poor sales and the risk that they would only make $35,000.

Finally, there is a way to align interests around outcomes without going fully to performance-based pay. If the manager for cultural reasons sees their interests as aligned, this may mitigate the principal-agent problem. In our example, suppose the store is in a small, tight-knit community with a strong sense of civic pride and familial ties.

Even if the manager is being managed in terms of their behavior, their cultural ties to the community or clan may lead them to see their interests as well aligned with those of the principal. As noted in [87], “Clan control implies goal congruence between people and, therefore, the reduced need to monitor behavior or outcomes. Motivation issues disappear.” We have discussed this kind of motivation in Chapter 7, especially in our discussion of control culture and insights drawn from the military.

COSO and control

Internal control is a process, effected by an entity’s board of directors, management, and other personnel, designed to provide reasonable assurance regarding the achievement of objectives relating to operations, reporting, and compliance.

Internal Control — Integrated Framework

An important discussion of governance is found in the statements of COSO on the general topic of "control.”

Control is a term with broader and narrower meanings in the context of governance. In the area of risk management, “controls” are specific approaches to mitigating risk. However, “control” is also used by COSO in a more general sense to clarify governance.

Control activities , according to COSO, are

the actions established through policies and procedures that help ensure that management’s directives to mitigate risks to the achievement of objectives are carried out. Control activities are performed at all levels of the entity, at various stages within business processes, and over the technology environment. They may be preventive or detective in nature and may encompass a range of manual and automated activities such as authorizations and approvals, verifications, reconciliations, and business performance reviews.

…Ongoing evaluations, built into business processes at different levels of the entity, provide timely information. Separate evaluations, conducted periodically, will vary in scope and frequency depending on assessment of risks, effectiveness of ongoing evaluations, and other management considerations. Findings are evaluated against criteria established by regulators, recognized standard-setting bodies or management and the board of directors, and deficiencies are communicated to management and the board of directors as appropriate. [73]

10.2.2. Analyzing governance

Governance context

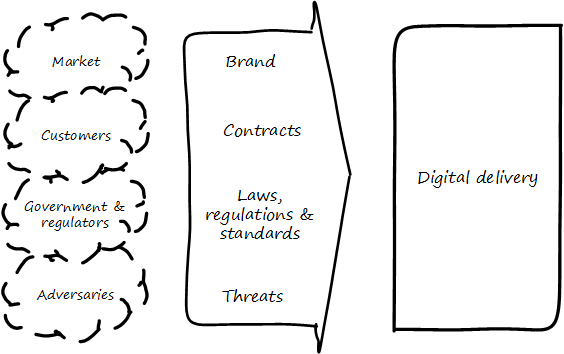

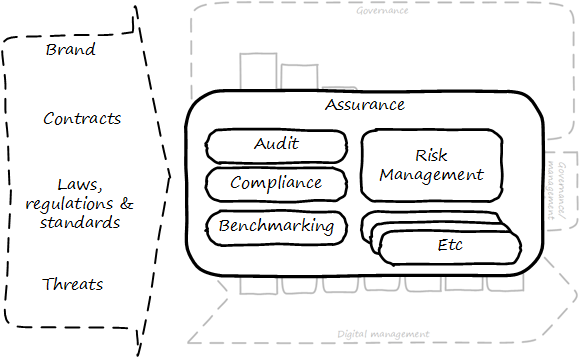

Enough theory. Governance is also a practical concern for you because, at your scale, you have a complex set of environmental forces to cope with (see Governance in context). You started with a focus on the customer, and the market they represented. Sooner or later, you encountered regulators and adversaries: competitors and cybercriminals.

These external parties intersect with your reality via various channels:

-

Your brand, which represents a sort of general promise to the market (see [261], p.16)

-

Contracts, which represent more specific promises to suppliers and customers

-

Laws, regulations, and standards, which can be seen as promises you must make and keep in order to function in civil society, or in order to obtain certain contracts.

-

Threats, which may be of various kinds:

-

legal

-

operational

-

intentional

-

unintentional

-

illegal

-

environmental

-

We will return to the role of external forces in our discussion of assurance. For now, we will turn to how digital governance, within an overall system of digital delivery, reflects our emergence model.

Governance and the emergence model

In terms of our emergence model, one of the most important distinctions between a “team of teams” and an “enterprise” is the existence of formalized organizational governance.

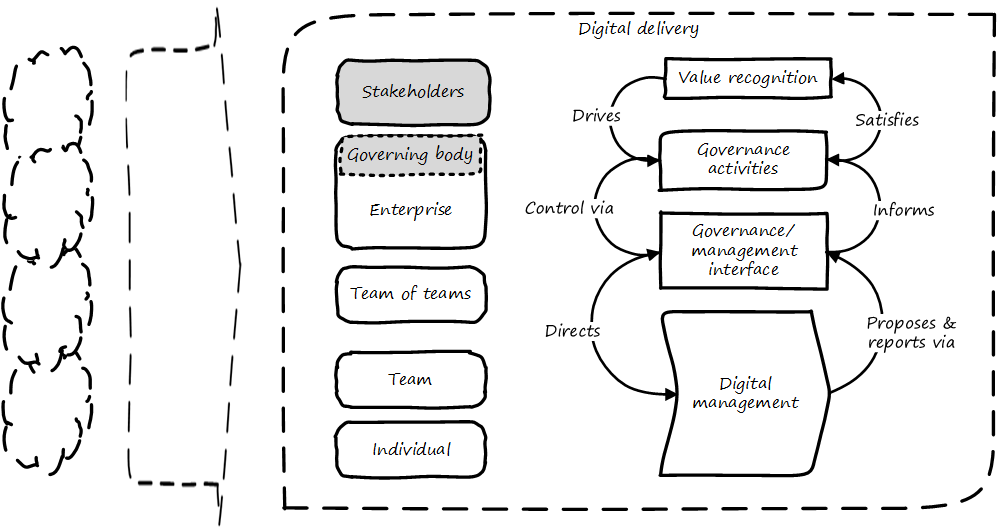

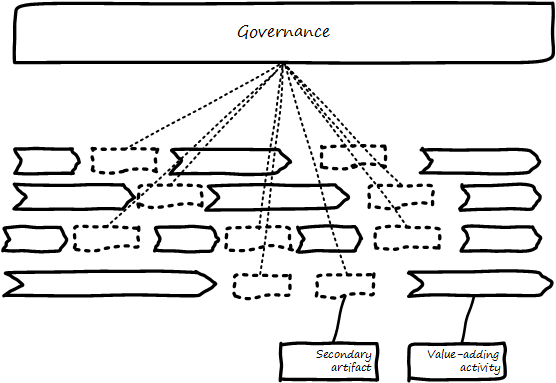

As illustrated in Governance emerges at the enterprise level, formalized governance is represented by the establishment of a governing body, responsive to some stakeholders who seek to recognize value from the organization or “entity” -— in this case, a digital delivery organization.

Corporate governance is a broad and deep topic, essential to the functioning of society and its organized participants. These include for-profit, non-profit, and even governmental organizations. Any legally organized entity of significant scope has governance needs.

One well known structure for organizational governance is seen in the regulated, publicly owned company (such as those listed on stock exchanges) . In this model, shareholders elect a governing body (usually termed the Board of Directors), and this group provides the essential direction for the enterprise as a whole.

However, organizational governance takes other forms. Public institutions of higher education may have a Board of Regents or Board of Governors, perhaps appointed by elected officials. Nonprofits and incorporated private companies still require some form of governance, as well. One of the less well-known but very influential forms of governance is the venture capital portfolio approach, very different from a public, mission-driven company. We will talk more about this in the digital governance section.

These are well known topics in law, finance, and social organization, and there are many sources you can turn to if you have further interest. If you are taking any courses in Finance or Accounting, you will likely cover governance objectives and processes.

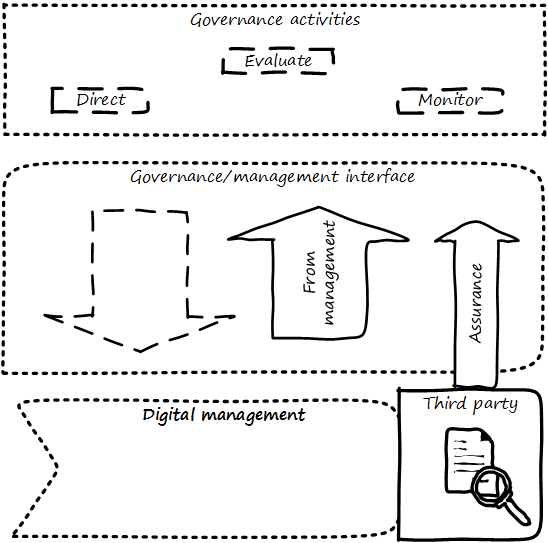

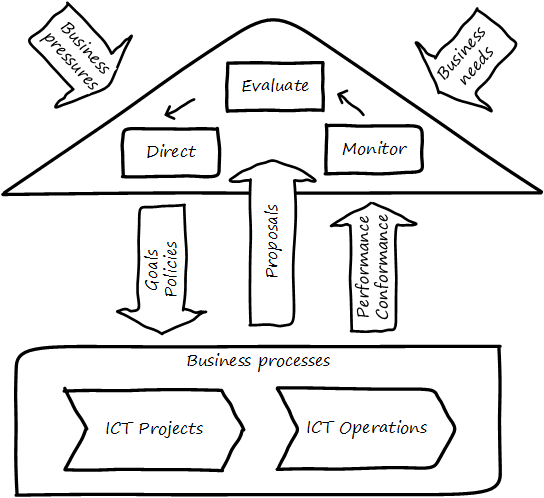

Illustrated in Governance and management with interface [4] is a more detailed visual representation of the relationship between governance and management in a digital context.

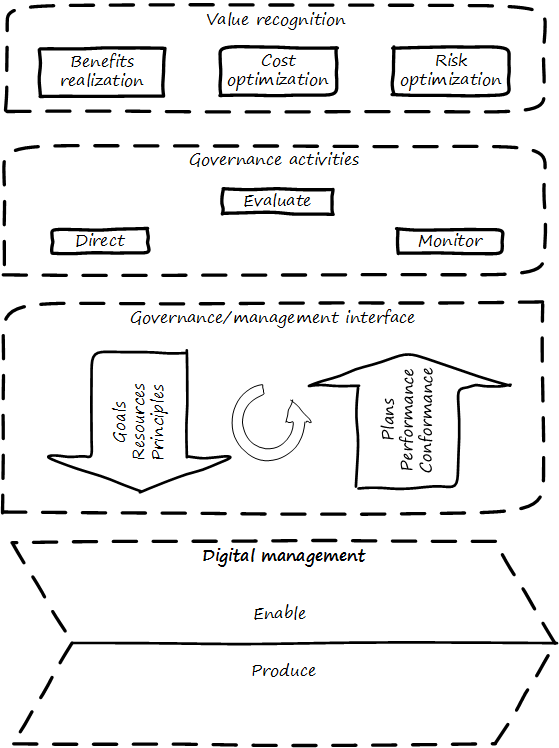

Reading the figure from the top down:

Value recognition is the fundamental objective of the stakeholder. We discussed in Chapter 4 the value objectives of effectiveness, efficiency, and risk (aka top line, bottom line, and risk). These are useful final targets for impact mapping, to demonstrate that lower level perhaps more “technical” product capabilities do ultimately contribute to organization outcomes.

|

Note

|

The term “value recognition” as the stakeholder goal is chosen over “value creation” as “creation” requires the entire system. Stakeholders do not “create” without the assistance of management, delivery teams, and the individual. |

Here, we see them from the stakeholder perspective of

-

Benefits realization

-

Cost optimization

-

Risk optimization

(Adapted from [136 p. 23])

Both ISO 38500 [142] as well as CObIT [136] specify that the fundamental governance activities of governance are:

-

Direct

-

Evaluate

-

Monitor

Evaluation is the analysis of current state, including current proposals and plans. Directing is the establishment of organizational intent as well as the authorization of resources. Monitoring is the ongoing attention to organizational status, as an input to evaluation and direction.

Direct, Evaluate, and Monitor may also be ordered as Evaluate, Direct, and Monitor. These are highly general concepts that in reality are performed simultaneously, not as any sort of strict sequence.

The governance/management interface is an essential component. The information flows across this interface are typically some form of the following:

From the governing side

-

Goals (e.g.,product and go-to-market strategies)

-

Resource authorizations (e.g.,organizational budget aprovals)

-

Principles and policies (e.g.,personnel and expense policies)

From the governed side

-

Plans & proposals (at a high level, e.g., budget requests)

-

Performance reports (e.g.,sales figures)

-

Conformance/compliance indicators (e.g.,via audit and assurance)

Notice also the circular arrow at the center of the Governance/Management interface. Governance is not a one-way street. Its principles may be stable, but approaches, tools, practices, processes, and so forth (what we will discuss below as “enablers,” in CObIT terminology) are variable and require ongoing evolution.

We often hear of “bureaucratic” governance processes. But the problem may not be “governance” per se. It is more often the failure to correctly manage the governance/management interface. Of course, if the board is micro-managing, demanding many different kinds of information and intervening in operations, then governance and its management response is all much the same thing. In reality, however, burdensome organizational “governance” processes may be an overdone, bottom-up management response to perceived Board-level mandates.

Or they may be point-in-time requirements no longer needed. The policies of 1960 are unsuited to the realities of 2020. But if policies are always dictated top-down, they may not be promptly corrected or retired when no longer applicable. Hence, the scope and approach of governance in terms of its enablers must always be a topic of ongoing, iterative negotiation between the governed and the governing.

Finally the lowermost digital delivery chevron -— aka value chain, represents most of what we have discussed in Sections I, II, and III:

-

the individual working to create value using digital infrastructure and lifecycle pipelines

-

the team collaborating to discover and deliver valuable digital products

-

the team of teams coordinating to deliver higher-order value while balancing effectiveness with efficiency and consistency

Ultimately, governance is about managing results and risk. It’s about objectives and outcomes. It’s about “what,” not “how.” In terms of practical usage, it is advisable to limit the “governance” domain -— including the use of the term -— to a narrow scope of the board or director-level concerns, and the existence of certain capabilities, including:

-

organizational policy management

-

external and internal assurance and audit

-

risk management, including security aspects

-

compliance

We turn to a useful concept for the implementation of digital governance -— the concept of enablers.

10.3. Enablers

10.3.1. An introduction to enablers

Enablers are factors that, individually and collectively, influence whether something will work — in this case, governance and management over enterprise IT.

ISACA

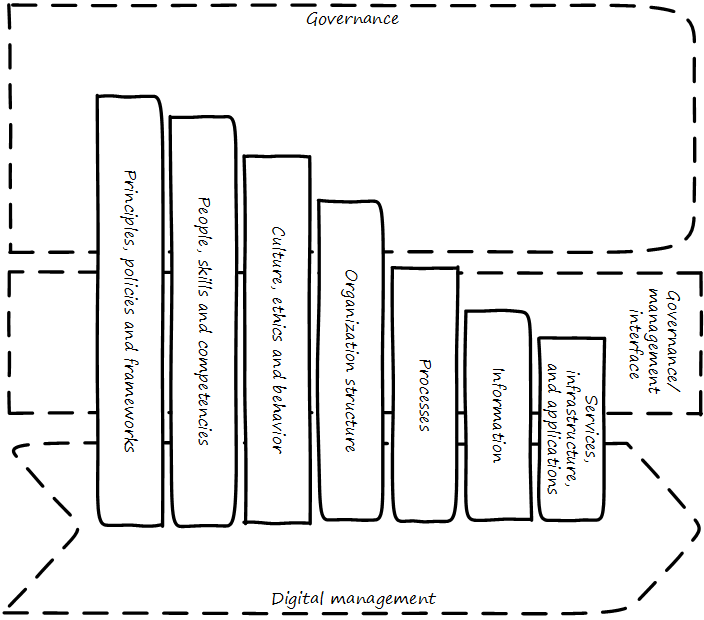

As we explore the goverance/management interface further, we encounter the CObIT concept of enablers [136] (see CObIT enablers across the governance interface).

Enablers are the fundamental components of any purposeful organization. CObIT has a detailed structure that positions enablers in a broader context of stakeholder objectives, enterprise and IT goals, and various quality criteria. One easy to understand example of a governance-level enabler concern is when processes serve as risk controls; we will discuss this further in the next chapter section.

CObIT’s 7 enablers are:

-

Principles, Policies, and Frameworks

-

Processes

-

Organizational Structures

-

Culture, Ethics, and Behavior

-

Information

-

Services, Infrastructure, and Applications

-

People, Skills, and Competencies

In the illustration, varying lengths of the enablers are deliberate. The further upward the bar extends, the more they are direct concerns for governance. All of the enablers are discussed elsewhere in the book.

| Enabler | Covered here |

|---|---|

Principles, Policies, and Frameworks |

Principles & policies covered in this chapter. Frameworks covered in Chapter 8 (PMBOK), Chapter 9 (CMMI, ITIL, CObIT, TOGAF), Chapter 11 (DMBOK), Chapter 12 (further TOGAF). |

Processes |

|

Organizational Structures |

|

Culture, Ethics and Behavior |

|

Information |

|

Services, Infrastructure, and Applications |

|

People, Skills, and Competencies |

Here, we are concerned with their aspect as presented to the governance interface; here are some notes.

Principles, policies, and frameworks

Principles are the most general statement of organizational vision and values. Policies will be discussed in detail in the next section. In general, they are binding organization mandates or regulations, sometimes grounded in external laws. Frameworks were defined in Chapter 8. We discuss all of these further in this chapter section.

|

Note

|

Some companies may need to institute formal policies quite early. Even a startup may need written policies if it is concerned with regulations such as HIPAA. However, this may be done on an ad hoc basis, perhaps outsourced to a consultant. (A startup cannot afford a dedicated VP of Policy and Compliance). This topic is covered in detail in this section because, at enterprise scale, ongoing policy management and compliance must be formalized. Recall that Emergence means formalization is the basis of our emergence model. |

People, skills, and competencies

People and their skills and competencies (covered in Chapter 8) are an enabler upon in which all the other enablers rest. “People are our #1 asset” may seem to be a cliche, but it is ultimately true. Formal approaches to understanding and managing this base of skills are therefore needed. A basic “Human Resources” capability is a start, but sophisticated and ambitious organizations institute formal organizational learning capabilities to ensure that talent remains a critical focus.

Culture, ethics and behavior

Organizational structures

We discussed basic organizational structure in Chapter 7. However, governance also may make use of some of the scaling approaches discussed in Chapter 8. Cross-organization coordination techniques (similar to those discussed in Chapter 8) are frequently used in governance (e.g.,cross-organizational coordinating committees, such as an enterprise security council).

Processes

Process was defined in Chapter 9. We will discuss enablers as controls in the upcoming chapter section on risk management. A control is a role that an enabler may play. Processes are the primary form of enabler used in this sense.

Information

Information is a general term; in the sense of an enabler, it is based on data in its various forms, with overlays of concepts (such as syntax and semantics) that transform raw “data” into a resource that is useful and valuable for given purposes. From a governance perspective, information carries governance direction to the governed system, and the fed back monitoring also is transmitted as information. Information resource management and related topics such as data governance and data quality are covered in Chapter 11; it is helpful to understand governance at an overall level before going into these more specific domains.

Services, infrastructure, and applications

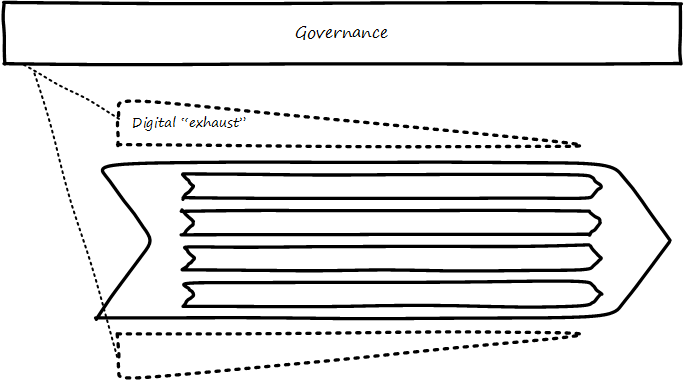

Services, infrastructure, and applications of course are the critical foundation of digital value. These fundamental topics were covered in Part I. In the sense of enablers, they have a recursive or self-reflexive quality. Digital technology automates business objectives; at scale, a digital pipeline becomes a nontrivial business concern in and of itself, requiring considerable automation [24], [204]. Applications that serve as digital governance enablers might include:

-

Source control

-

Build management

-

Package management

-

Deployment and configuration management

-

Monitoring

-

Portfolio management

10.3.2. One-way policy begins

Your company was incorporated long ago, but the “board” was always a bit of a joke. The three people who started the company were the directors of record, and they would have an annual “meeting” at the local bar where enough paperwork would be done to satisfy the company lawyer.

Your company did well and accumulated enough cash to purchase another company, run in much the same way. The people who owned the company being acquired were good, and your company didn’t want to lose them, so in addition to senior management positions, they were offered equity -— a share of ownership in the new combined firm.

This raised the topic, “how is the new firm directed?” One of the incoming shareholders wanted a seat on the “board,” even though neither company had done much with board-level governance.

The lawyer and accountant hired to assist with the merger also recommended that as part of the acquisition, a formal audit is to be conducted of both firms (which had never been done).

This audit came back generally clean but shone a light on differences in how the companies had operated, and unearthed some irregularities.

For example, your company had started to purchase phones for all employees, while the acquired company was pure BYOD (Bring Your Own Device). One company had corporate credit cards, while the other was requiring people to carry their own expenses for reimbursement. One company had an informal “understanding” that first class travel was OK for Asian trips at least, while the other didn’t, but neither had written anything down. And so on.

The lawyer said, “I think you need some policies,” and everybody groaned. One person said, “I just read about Nordstrom. All they say is “Use Good Judgment.” Why do we need anything more?”

The lawyer said, “Um, that’s an urban legend. The actual Nordstrom Code of Business Conduct and Ethics, while it starts off with that, runs about 8,000 words and covers a variety of topics such as handling customer information, using technology, social media, and so forth.”

And the new CFO said, “Look, I get that we want to stay agile, and keep our informal culture. I’m no fan of policy for the sake of policy. But I need those policies to keep my staff costs down. Two different expense approaches don’t add any value to us, and that’s only one of twenty issues we’ve uncovered here. \'Do the right thing' doesn’t cut it. We’ve got to have some means of establishing a baseline for new employees, someplace people can turn to when they don’t know what the expectation is.”

The HR director chimed in. “If we don’t document our official position on things like harassment we are going to have problems. We could fire someone who has done something really bad, and they could sue us for wrongful termination. Or their victims could sue us for failing to prevent the issue. That could cost us real money.” The lawyer nodded, and the company owners looked thoughtful.

Another person spoke up. “I came from a company that had a 500-page policy manual. It went down into way too much detail and was always out of date. No-one could find anything in it, and there would be stuff that was wrong because the revision process was broken.”

The lawyer said, “You need to keep your policies light and on the general side (like Nordstrom) and cover more detailed topics elsewhere. For example, the exact approach on how to reimburse employee expenses probably doesn’t belong in the policy manual. Of course, that means that somewhere you need to lay out how your principles inform your policies which are implemented by processes, procedures, guidelines, and so forth. Your actual employee handbook will probably be thirty or forty pages — sorry. You also should take advantage of your internal intranet and make sure people can find just the policy they need, with related guidance, instead of having to page through a huge document.

“Finally, you need to carefully distribute the authorship and revision control, especially for lower levels of the guidance (e.g.,technical standards that can change quickly). This is both because the people most affected should have a stronger voice in the policy, and also because centralized policy groups become bottlenecks if they are doing all the work.”

Another said, “This is all getting complicated.”

“Yes, complexity is to some extent unavoidable as you move to this new scale. I’m a big fan of sunset dates on policies and supporting materials, so you are periodically questioning whether something is still needed. Of course, this drives demand for someone to analyze and update policies — please don’t forget that.

“Overall, you need to always keep your outcomes in mind, and continue to push as much decision making down to individuals as you can. CObIT recognizes that culture is one of the critical enablers for governance, and so 'use good judgment' is still a great place to start -— IF you can hire people with good judgment, and continually reinforce them in using it.”

10.3.3. Mission, principle, strategy, and policy

Carefully drafted and standardized policies and procedures save the company countless hours of management time. The consistent use and interpretation of such policies, in an evenhanded and fair manner, reduces management’s concern about legal issues becoming legal problems.

“How To Write a Policy Manual"

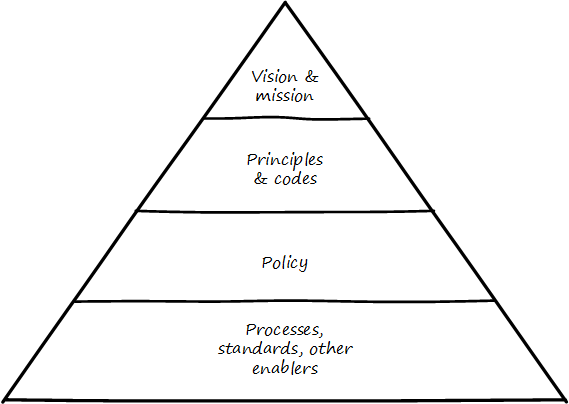

Illustrated in Vision/mission/policy hierarchy is one way to think about policy in the context of our overall governance objective of value recognition.

The organization’s vision and mission should be terse and high level, perhaps something that could fit on a business card. It should express the organization’s reason for being in straightforward terms. Mission is reason for being; vision is a “picture” of the future, preferably inspirational.

The principles and codes should also be brief. (“Codes” can include codes of ethics or codes of conduct). For example, Nordstrom’s is about 8,000 words, perhaps about 10 pages.

Policies are more extensive. There are various kinds of policies:

In a non-IT example, a compliance policy might identify the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and make it clear that bribery of foreign officials is unacceptable. Similarly, an HR policy might spell out acceptable and unacceptable side jobs (e.g., someone in the banking industry might be forbidden from also being a mortgage broker on their own account).

Policies are often independently maintained documents, perhaps organized along lines similar to:

-

Employment and HR policies

-

Whistleblower policy (non-retaliation)

-

Records retention

-

Privacy

-

Workplace guidelines

-

Travel and expense

-

Purchasing and vendor relationships

-

Use of enterprise resources

-

Information security

-

Conflicts of interest

-

Regulatory

(not a comprehensive list)

Policies, even though more detailed than codes of ethics/conduct, still should be written fairly broadly. In many organizations, they must be approved by the governing board. They should, therefore, be independent of technology specifics. An information security policy may state that the hardening guidelines must be followed, but the hardening guidelines (stipulating for example what services and open ports are allowable on Debian Linux) are not policy. There may be various levels or classes of policy.

Finally, policies reference standards and processes and other enablers as appropriate. This is the management level, where documentation is specific and actionable. Guidance here may include:

-

Standards

-

Baselines

-

Guidelines

-

Processes and procedures

These concepts may vary according to organization, and can become quite detailed. Greater detail is achieved in hardening guidelines. A behavioral baseline might be “Guests are expected to sign in and be accompanied when on the data center floor.” We will discuss technical baselines further in the chapter section on security, and also in our discussion of the technology product lifecycle in Chapter 12. See also Shon Harris' excellent CISSP Exam Guide [119] for much more detail on these topics.

The ideal end state is a policy that is completely traceable to various automation characteristics, such as approved “infrastructure as code” settings applied automatically by configuration management software (as discussed in “The DevOps Audit Toolkit,” [80]-— more on this to come). However, there will always be organizational concerns that cannot be fully automated in such manners.

Policies (and their implementation as processes, standards, and the like) must be enforced. As Steve Schlarman notes “Policy without a corresponding compliance measurement and monitoring strategy will be looked at as unrealistic, ignored dogma.” [236]

Policies and their derivative guidance are developed, just like systems, via a lifecycle. They require some initial vision and an understanding of what the requirements are. Again, Schlarman: “policy must define the why, what, who, where and how of the IT process” [236]. User stories have been used effectively to understand policy needs.

Finally, an important point to bear in mind:

Company policies can breed and multiply to a point where they can hinder innovation and risk-taking. Things can get out of hand as people generate policies to respond to one-time infractions or out of the ordinary situations [112 p. 17].

It’s advisable to institute sunset dates or some other mechanism that forces their periodic review, with the understanding that any such approach generates demand on the organization that must be funded. We will discuss this more in the chapter section on digital governance.

10.3.4. Standards, frameworks, methods, and the innovation cycle

We used the term “standards” above without fully defining it. We have discussed a variety of industry influences throughout this book: PMBOK, ITIL, CObIT, Scrum, Kanban, ISO/IEC 38500 and so on. We need to clarify their roles and positioning further. All of these can be considered various forms of “guidance” and as such are governance enablers. However, their origins, stakeholders, format, content, and usage vary greatly.

First, the term "standard” especially has multiple meanings. A “standard” in the policy sense may be a set of compulsory rules. Also, “standard” or “baseline” may refer to some intended or documented state the organization uses as a reference point. An example might be “we run Debian Linux 16_10 as a standard unless there is a compelling business reason to do otherwise.”

This last usage shades into a third meaning of uniform, normative standards such as are produced by the IEEE, IETF and ISO/IEC.

-

ISO/IEC: Internatonal Standards Organization/International Eletrotechnical Commission

-

IETF: Internet Engineering Task Force

-

IEEE: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers

The International Standards Organization, or ISO, occupies a central place in this ecosystem. It possesses “general consultative status” with the United Nations, and has over 250 technical committees that develop the actual standards.

The IEEE standardizes such matters as wireless networking (e.g.,WiFi). The IETF (Internet Engineering Task Force) standardizes lower level Internet protocols such as TCP/IP and HTTP. The W3C (World Wide Web Consortium) standardizes higher-level Internet protocols such as HTML. Sometimes standards are first developed by a group such as the IEEE and then given further authority though publication by ISO/IEC. The ISO/IEC in particular, in addition to its technical standards, also develops higher order management/"best practice” standards. One well known example of such an ISO standard is the ISO 9000 series on quality management.

Some of these standards may have a great effect on the digital organization. We’ll discuss this further in the chapter section on compliance.

Frameworks were discussed in Chapter 9. Frameworks have two major meanings. First, software frameworks are created to make software development easier. Examples include Struts, AngularJS, and many others. This is a highly volatile area of technology, with new frameworks appearing every year and older ones gradually losing favor.

In general we are not concerned with these kinds of specific frameworks in this book, except governing them as part of the technology product lifecycle. We are concerned with “process” frameworks such as ITIL, PMBOK, CObIT, CMMI, and the TOGAF framework. These frameworks are not “standards” in and of themselves. However, they often have related ISO standards:

| Framework | Standard |

|---|---|

ITIL |

ISO/IEC 20000 |

CObIT |

ISO/IEC 38500 |

PMBOK |

ISO/IEC 21500 |

CMMI |

ISO/IEC 15504 |

TOGAF |

ISO/IEC 42010 |

Frameworks tend to be lengthy and verbose. The ISO/IEC standards are brief by comparison, perhaps on average 10% of the related framework. Methods (aka methodologies) in general are more action oriented and prescriptive. Scrum and XP are methods. It is at least arguable that PMBOK is a method as well as a framework.

|

Note

|

There is little industry consensus on some of these definitional issues, and the student is advised not to be overly concerned about such abstract debates. If you need to comply with something to win a contract, it doesn’t matter whether it’s a “standard,” “framework,” “guidance,” “method,” or what have you. |

Finally, there are terms that indicate technology cycles, movements, communities of interest, or cultural trends: Agile and DevOps being two of the most current and notable. These are neither frameworks, standards, nor methods. However, commercial interests often attempt to build frameworks and methods representing these organic trends. Examples include the Scaled Agile Framework, Disciplined Agile Delivery, the DevOps Institute, the DevOps Agile Skills Association, and many others.

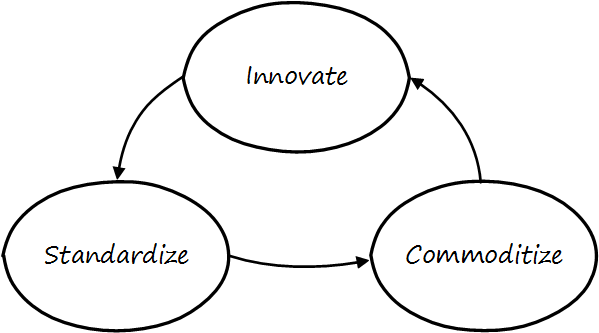

Innovation cycle illustrates the innovation cycle. Innovations produce value, but innovation presents change management challenges, such as cost and complexity. The natural response is to standardize for efficiency, and standardization taken to its end state results in commodification, where costs are optimized as far as possible, and the remaining concern is managing the risk of the commodity (as either consumer or producer). While efficient, commoditized environments offer little competitive value, and so the innovation cycle starts again.

Note that the innovation cycle corresponds to the elements of value recognition:

-

Innovation corresponds to Benefits Realization

-

Standardization corresponds to Cost Optimization

-

Commoditization corresponds to Risk Optimization

10.4. Risk management

10.4.1. Risk management fundamentals

Risk is defined as the possibility that an event will occur and adversely affect the achievement of objectives.

Internal Control — Integrated Framework

Risk is a fundamental concern of governance. Management (as we have defined it in this chapter section) may focus on effectiveness and efficiency well enough, but too often disregards risk.

As we noted above, the shop manager may have incentives to maximize income, but usually, does not stand to lose their life savings. The owner, however, does. Fire, theft, disaster — without risk management, the owner does not sleep well.

For this reason, risk management is a large element of governance, as indicated by the popular GRC acronym: governance, risk, and compliance.

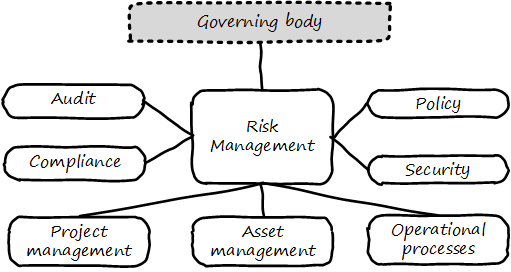

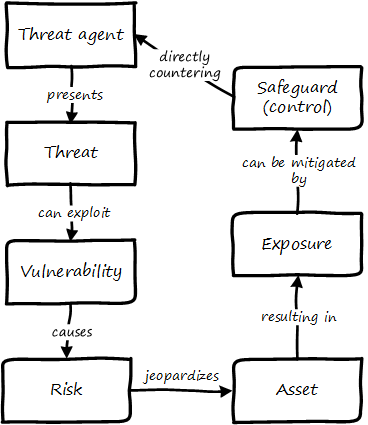

Risk management can be seen as both a function and a process (see Risk management context). As a function, it may be managed by a dedicated organization (perhaps called Enterprise Risk Management or Operational Risk Management). As a process, it conducts the following activities:

-

Identifying risks

-

Assessing and prioritizing them

-

Coordinating effective responses to risks

-

Ongoing monitoring and reporting of risk management

Risk impacts some asset. Examples in the digital and IT context would include:

-

Operational IT systems

-

Hardware (e.g.,computers) and facilities (e.g.,data centers)

-

Information (customer or patient records)

It is commonly said that organizations have an “appetite” for risk [139 p. 79], in terms of the amount of risk the organization is willing to accept. This is a strategic decision, usually reserved for organizational governance.

Risk management typically has strong relationships with the following organizational capabilities:

-

Enterprise governance (e.g.,board-level committees)

-

Security

-

Compliance

-

Audit

-

Policy management

For example, security requires risk assessment as an input, so that security resources focus on the correct priorities. Risk additionally may interact with:

-

Project management

-

Asset management

-

Processes such as Change Management

and other digital activities. More detail on core risk management activities follows, largely adopted from the CObIT for Risk publication [139].

Risk identification

There are a wide variety of potential risks, and many accounts and anecdotes constantly circulating. It is critical that risk identification begins with a firm understanding of the organization’s objectives and context.

Risk identification can occur both in a “top down” and “bottom up” manner. Industry guidance can assist the operational risk management function in identifying typical risks. For example, the CObIT for Risk publication includes a useful 8 page “Generic Risk Scenarios” section [139 pp. 67-74] identifying risks such as

-

“Wrong programmes are selected for implementation and are misaligned with corporate strategy and priorities”

-

“There is an earthquake.”

-

“Sensitive data is lost/disclosed through logical attacks.”

These are only three of dozens of scenarios. Risks, of course, extend over a wide variety of areas:

-

Investment

-

Sourcing

-

Operations

-

Availability

-

Continuity

-

Security

and so forth. The same guidance also strongly cautions against over-reliance on these generic scenarios.

Risk assessment

Risk management has a variety of concepts and techniques both qualitative and quantitative. Risk is often assumed to be the product of probability * impact. For example, if the chance of a fire in a facility is 5% over a given year, and the damage of the fire is estimated at $100,000, the annual risk is $5,000. An enterprise risk management function may attempt to quantify all such risks into an overall portfolio.

Where quantitative approaches are perceived to be difficult, risk may be assessed using simple ordinal scales (e.g.,1-5, where 1 is low risk, and 5 is high risk). CObIT for Risk expresses concern regarding “The use of ordinal scales for expressing risk in different categories, and the mathematical difficulties or dangers of using these numbers to do any sort of calculation.” [139 p. 75]. Such approaches are criticized by Doug Hubbard in The Failure of Risk Management as misleading and potentially more harmful than not managing risk at all [126].

Hubbard instead suggests that quantitative techniques such as Monte Carlo analysis are rarely infeasible, and recommends their application instead of subjective scales.

The enterprise can also consider evaluating scenarios that have a chance of occurring simultaneously. This is frequently referred to as ‘stress’ testing.

Risk response

He who fights and runs away lives to fight another day.

342 BC — 291 BC

Risk response includes several approaches:

-

Avoidance

-

Acceptance

-

Transference

-

Mitigation

Avoidance means ending the activities or conditions causing the risk; e.g., not engaging in a given initiative or moving operations away from risk factors.

Acceptance means no action is taken. Typically, such “acceptance” must reside with an executive.

Transference means that some sharing arrangement, usually involving financial consideration, is established. Common transfer mechanisms include outsourcing and insurance. (Recall our discussion of Agile approaches to contract management and risk sharing).

Mitigation means that some compensating mechanism -— one or more “controls” is established. This topic is covered in the next section and comprises the remainder of the material on risk management.

(The above discussion was largely derived from ISACA’s CObIT 5 for Risk [138]).

Controls

The term 'control objective' is no longer a mainstream term used in CObIT 5, and the word 'control' is used only rarely. Instead, CObIT 5 uses the concepts of process practices and process activities.

CObIT 5 for Assurance

The term “control” is problematic.

It has distasteful connotations to those who casually encounter it, evoking images of "command and control” management, or “controlling” personalities. CObIT, which once stood for Control Objectives for IT, now deprecates the term control (see the above quote). Yet it retains a prominent role in many discussions of enterprise governance and risk management, as we saw at the start of this chapter in the discussion of COSO’s general concept of control.

And (as discussed in our coverage of Scrum’s origins) it is a technical term of art in systems engineering. As such it represents principles essential to understanding large scale digital organizations.

In this section, we are concerned with controls in a narrower sense, as risk mitigators. As noted above, ISACA replaced the term “controls” with process practices & activities, which are specific examples of enablers. As controls, enablers such as policies, procedures, organizational structures, and the rest are used and intended to ensure that:

-

investments achieve their intended outcomes;

-

resources are used responsibly, and protected from fraud, theft, abuse, waste, and mismanagement;

-

laws and regulations are adhered to; and

-

timely and reliable information is employed for decision making.

|

Note

|

You will likely encounter the term control as “testing enablers” or “testing process practices” is not how security personnel and auditors talk. |

But what are examples of “controls"? Take a risk, such as the risk of a service (e.g.,e-commerce website) outage resulting in loss of critical revenues. There are a number of ways we might attempt to mitigate this risk:

-

Configuration management (a preventative control)

-

Effective monitoring of system alerts (a detective control)

-

Documented operational responses to detected issues (a corrective control)

-

Clear recovery protocols that are practiced and well understood (a recovery control)

-

System redundancy of key components where appropriate (a compensating control)

and so forth. Another kind of control appropriate to other risks is deterrent (e.g.,an armed guard at a bank).

Other types of frequently seen controls include:

-

Separation of duties

-

Audit trails

-

Documentation

-

Standards and guidelines

A control type such as "separation of duties” is very general and might be specified by activity type, e.g.

-

Purchasing

-

System development and release

-

Sales revenue recognition

Each of these would require distinct approaches to separation of duties. Some of this may be explicitly defined; if there is no policy or control specific to a given activity, an auditor may identify this as a deficiency.

Policies and processes in their aspect as controls are often what auditors test. In the case of the website above, an auditor might test the configuration management approach, the operational processes, inspect the system redundancy, and so forth. And risk management would maintain an ongoing interest in the system in between audits.

As with most topics in this book, risk management (in and of itself, as well as applied to IT and digital) is an extensive and complex domain, and this discussion was necessarily brief. The student is referred to the readings at the end of the chapter for further information.

Business continuity

Business continuity is an applied domain of digital and IT risk, like security. Continuity is concerned with large scale disruptions to organizational operations, such as:

-

Floods

-

Earthquakes

-

Tornadoes

-

Terrorism

-

Hurricanes

-

Industrial catastrophes (e.g.,large scale chemical spills)

A distinction is commonly made between business continuity planning and disaster planning.

Disaster recovery is more tactical, including the specific actions taken during the disaster to mitigate damage and restore operations, and often with an IT-specific emphasis.

Continuity planning takes a longer term view of matters such as long-term availability of replacement space and computing capacity.

There are a variety of standards covering business continuity planning, including:

-

NIST Special Publication 800-34

-

ISO/IEC 27031:2011

-

ISO 22301

In general, continuity planning starts with understanding the business impact of various disaster scenarios and developing plans to counter them. Traditional guidance suggests that this should be achieved in a centralized fashion; however, large, centralized efforts of this nature tend to struggle for funding.

While automation alone cannot solve problems such as “where do we put the people if our main call center is destroyed,” it can help considerably in terms of recovering from disasters. If a company has been diligent in applying infrastructure as code techniques, and loses its data center, it can theoretically re-establish its system configurations readily, which can otherwise be a very challenging process, especially under time constraints. (Data still needs to have been backed up to multiple locations).

10.4.2. Compliance

Compliance is a very general term meaning conformity or adherence to

-

laws

-

regulations

-

policies

-

contracts

-

standards

and the like. Corporate compliance functions may first be attentive to legal and regulatory compliance, but the other forms of compliance are matters of concern as well.

A corporate compliance office may be responsible for the maintenance of organizational policies and related training and education, perhaps in partnership with the human resources department. They also may monitor and report on the state of organizational compliance. Compliance offices may also be responsible for codes of ethics. Finally, they may manage channels for anonymous reporting of ethics and policy violations by whistleblowers (individuals who become aware of and wish to report violations while receiving guarantees of protection from retaliation).

Compliance uses techniques similar to risk management, and in fact, non-compliance can be managed as a form of risk, and prioritized and handled much the same way. However, compliance is an information problem as well as a risk problem. There is an ongoing stream of regulations to track, which keeps compliance professionals very busy. In the U.S. alone, these include:

-

HIPAA

-

SOX

-

FERPA

-

PCI DSS

-

GLBA PII

Some of these regulations specifically call for policy management, and therefore companies that are subject to them may need to institute formal governance earlier than other companies, in terms of the emergence model. Many of them provide penalties for the mis-management of data, which we will discuss further in the next chapter section and in Chapter 11. Compliance also includes compliance with the courts (e.g.,civil and criminal actions). This will be discussed in the Chapter 11 section on cyberlaw.

10.5. Assurance and audit

10.5.1. Assurance

Trust, but verify.

Assurance is a broad term. In this book, it is associated with governance. It represents a form of additional confirmation that management is performing its tasks adequately. Go back to the example that started the chapter, of the shop owner hiring a manager. Suppose that this relationship has continued for some time, and while things seem to be working well, the owner has doubts about the arrangement. Over time, things have gone well enough that the owner does not worry about the shop being opened on time, having sufficient stock, or paying suppliers. But are any number of doubts the owner might retain:

-

Is money being accounted for honestly and accurately?

-

Is the shop clean? Is it following local regulations? For example, fire, health and safety codes?

-

If the manager selects a new supplier, are they trustworthy? Or is the shop at risk of selling counterfeit or tainted merchandise?

-

Are the shop’s prices competitive? Is it still well regarded in the community? Or has its reputation declined with the new manager?

-

Is the shop protected from theft and disaster?

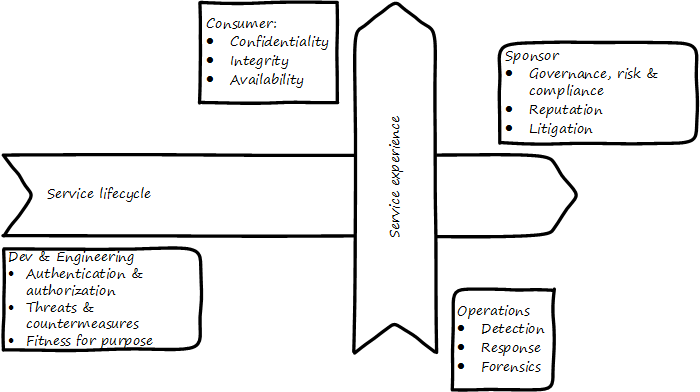

These kinds of concerns remain with the owner, by and large, even with a reliable and trustworthy manager. If not handled correctly, the owner’s entire investment is at risk. The manager may only have a salary (and perhaps a profit share) to worry about, but if the shop is closed due to violations, or lawsuit, or lost to a fire, the owner’s entire life investment may be lost. These concerns give rise to the general concept of assurance, which applies to digital business just as it does to small retail shops. The following diagram, derived from previous illustrations, shows how this book views assurance: as a set of practices overlaid across the enablers, and in particular concerned with external forces (see Assurance in context).

As ISACA stipulates,

The IS audit and assurance function shall be independent of the area or activity being reviewed to permit objective completion of the audit and assurance engagement. [141 p. 9]. Assurance can be seen as an external, additional mechanism of control and feedback. This independent, out-of-band aspect is essential to the concept of assurance (see Assurance is an objective, external mechanism).

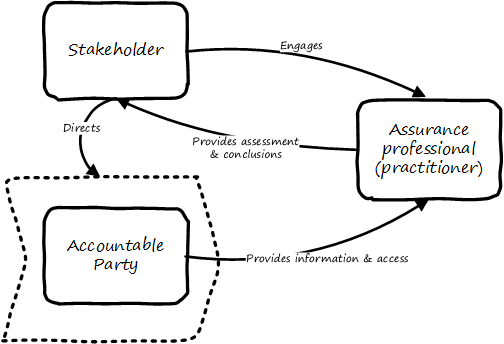

Three party foundation

Assurance means that pursuant to an accountability relationship between two or more parties, an IT audit and assurance professional may be engaged to issue a written communication expressing a conclusion about the subject matters to the accountable party.

There are broader and narrower definitions of assurance. But all reflect some kind of three-party arrangement (see Assurance is based on a three-party model [5])

The above diagram is one common scenario:

-

The stakeholder (e.g.,the audit committee of the board of directors) engages an assurance professional (e.g.,an audit firm). The scope and approach of this are determined by the engaging party, although the accountable party in practice often has input as well.

-

The accountable party, at the direction, responds to the assurance professional’s inquiries on the audit topic.

-

The assurance professional provides the assessment back to the engaging party, and/or other users of the report (potentially including the accountable party).

This is a simplified view of what can be a more complex process and set of relationships. The ISAE3000 standard states that there must be at least three parties to any assurance engagement:

-

The responsible (accountable) party

-

The practitioner

-

The intended users (of the assurance report)

But there may be additional parties:

-

The engaging party

-

The measuring/evaluating party (sometimes not the practitioner, who may be called on to render an opinion on someone else’s measurement)

ISAE3000 goes on to stipulate a complex set of business rules for the allowable relationships between these parties [133 pp. 95-96]. Perhaps the most important rule is that the practitioner cannot be the same as either the responsible party or the intended users. There must be some level of professional objectivity.

What’s the difference between assurance and simple consulting? There are two major factors:

-

Consulting can be simply a two-party relationship — a manager hires someone for advice

-

Consultants do not necessarily apply strong assessment criteria. Indeed, with complex problems, there may not be any such criteria. Assurance, in general, presupposes some existing standard of practice, or at least some benchmark external to the organization being assessed.

Finally, the concept of assurance criteria is key. Some assurance is executed against the responsible party’s own criteria. In this form of assurance, the primary questions are “are you documenting what you do, and doing what you document?” That is, for example, do you have formal process management documentation (as discussed in Chapter 9)? And are you following it?

Other forms of assurance use external criteria. A good example is the Uptime Institute's data center tier certification criteria, discussed below. If criteria are weak or non-existent, the assurance engagement may be more correctly termed an advisory effort. Assurance requires clarity on this topic.

Types of assurance

Exercise caution in your business affairs; for the world is full of trickery.

“Desiderata"

The general topic of “assurance” implies a spectrum of activities. In the strictest definitions, assurance is provided by licensed professionals under highly formalized arrangements. However, while all audit is assurance, not all assurance is audit. As noted in CObIT for Assurance, “assurance also covers evaluation activities not governed by internal and/or external audit standards.” [138 p. 15].

This is a blurry boundary in practice, as an assurance engagement may be undertaken by auditors, and then might be casually called an “audit” by the parties involved. And there is a spectrum of organizational activities that seem at least to be related to formal assurance:

-

Brand assurance

-

Quality assurance

-

Vendor assurance

-

Capability assessments

-

Attestation services

-

Certification services

-

Compliance

-

Risk management

-

Benchmarking

-

Other forms of “due diligence”

Some of these activities may be managed primarily internally, but even in the case of internally-managed activities, there is usually some sense of governance, some desire for objectivity.

From a purist perspective, internally directed assurance is a contradiction in terms. There is a conflict of interest in that in terms of the three-party model above, the accountable party is the practitioner.

However, it may well be less expensive for an organization to fund and sustain internal assurance capabilities and get much of the same benefits as from external parties. This requires sufficient organizational safeguards be instituted. Internal auditors typically report directly to the Board-level audit committee, and generally, are not seen as having a conflict of interest.

In another example, an internal compliance function might report to the corporate general counsel (chief lawyer), and not to any executive whose performance is judged based on their organization’s compliance -— this would be a conflict of interest. However, because the internal compliance function is ultimately under the CEO, their concerns can be overruled.

The various ways that internal and external assurance arrangements can work, and can go wrong, is a long history. If you are interested in the topic, review the histories of Enron, Worldcom, the 2008 mortgage crisis, and other such failures.

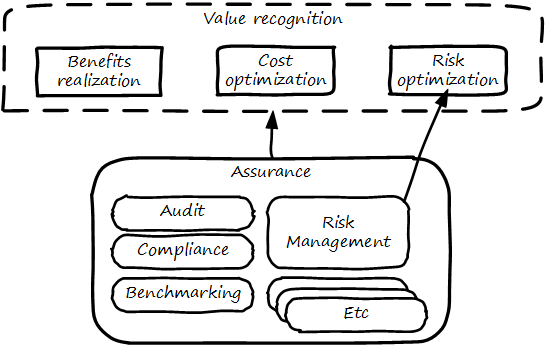

Assurance and risk management

Risk management (discussed in the previous chapter section) may be seen as part of a broader assurance ecosystem. For evidence of this, consider that the Institute of Internal Auditors offers a certificate in Risk Management Assurance; The Open Group also operates the Open FAIR™ Certification Program. Assurance in practice may seem to be biased towards risk management, but (as with governance in general) assurance as a whole relates to all aspects of IT and digital governance, including effectiveness and efficiency.

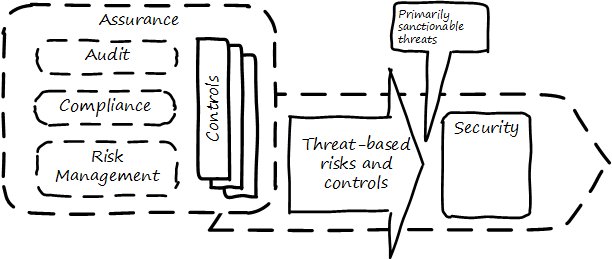

Audit practices may be informed of known risks and particularly concerned with their mitigation, but risk management remains a distinct practice. Audits may have scope beyond risks, and audits are only one tool used by risk management (see Assurance and risk management).

In short, and as shown in the following diagram, assurance plays a role across value recognition, while risk management specifically targets the value recognition objective of risk optimization.

Non-audit assurance examples

Businesses must find a level of trust between each other . . . 3rd party reports provide that confidence. Those issuing the reports stake their name and liability with each issuance.

“Successfully Establishing and Representing DevOps in an Audit"

Before we turn to a more detailed discussion of the audit, we’ll discuss some specifically non-audit examples of assurance seen in IT and digital management.

Example 1: Due diligence on a cloud provider

Your company is considering a major move to cloud infrastructure for its systems. The agility value proposition -— the ability to minimize cost of delay -— is compelling, and there may be some cost structure advantages as well.

But you are aware of some cloud failures:

-

In 2013, UK cloud provider 2e2 went bankrupt, and customers were given “24 to 48 hours to get … data and systems out and into a new environment” [85]. Subsequently, the provider demanded nearly 1 million pounds (roughly $1.5 million) from its customers in order for their uninterrupted access to services (i.e., their data). [275]

-

Also in 2013, cloud storage provider Nirvanix went bankrupt, and its customers also had a limited time to remove their data. MegaCloud went out of business with no warning two months later, and all customers lost all data. [48], [49]

-

In mid-2014, online source code repository Cloud Spaces (an early Github competitor) was taken over by hackers and destroyed. All data was lost. [274], [179]

The question is, how do you manage the risks of trusting your data and organizational operations to a cloud provider? This is not a new question, as computing has been outsourced to specialist firms for many years. You want to be sure that their operations meet certain standards:

-

Financial standards

-

Operational standards

-

Security standards

Data center evaluations of cloud providers are a form of assurance. Two well known approaches are:

-

The Uptime Institute’s Tier Certification

-

The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants' (AICPA) SOC 3 “Trust Services Report” certifying “Service Organizations” (based in turn on the SSAE-16 standard)

The Uptime Institute provides the well-known “Tier” concept for certifying data centers, from Tier I to Tier IV. In their words, “Certification provides assurances that there are not shortfalls or weak links anywhere in the data center infrastructure.” [273]. The Tiers progress as follows [272]:

-

Tier I: Basic Capacity

-

Tier II: Redundant Capacity Components

-

Tier III: Concurrently Maintainable

-

Tier IV: Fault Tolerance

Uptime Institute certification is a generic form of assurance in terms of the 3-party model; the data center operator must work with the Uptime Institute who provides an independent opinion based on their criteria as to the data center’s tier (and therefore effecctiveness).

The SOC 3 report is considered an “assurance” standard as well. However, as mentioned above, this is the kind of “assurance” done in general by licensed auditors, and which might casually be called an “audit” by the participants. A qualified professional, again in the 3-party model, examines the data center in terms of the SSAE 16 reporting standard.

Your internal risk management organization might look to both Uptime Institute and SOC 3 certification as indicators that your cloud provider risk is mitigated. (More on this in chapter section on Risk Management).

Example 2: Internal process assessment

You may also have concerns about your internal operations. Perhaps your process for selecting technology vendors is unsatisfactory in general; it takes too long and yet vendors with critical weaknesses have been selected.

More generally, the actual practices of various areas in your organization may be assessed by external consultants using the related guidance:

-

Enterprise Architecture with the TOGAF ADM

-

Project Management with PMBOK

-

IT processes such as Incident Management, Change Management, and Release Management with ITIL or CMMI-SVC

These assessments may be performed through using a maturity scale, e.g., CMM-derived. The CMM-influenced ISO/IEC 15504 standard may be used as a general process assessment framework. (Remember that we have discussed the problems with the fundamental CMM assumptions on which such assessments are based).

According to [21], “In our own experience, we have seen that the maturity models have their limitations.” They warn that maturity assessments of Enterprise Architecture at least are prone to being:

-

Subjective

-

Academic

-

Easily manipulated

-

Bureaucratic

-

Superfluous

-

Misleading

Those issues may well apply to all forms of maturity assessments. Let the buyer beware. At least, the concept of maturity should be very carefully defined in a manner relevant to the organization being assessed.

Example 3: Competitive benchmarking

Finally, you may wonder, “how does my digital operation compare to other companies?” Now, it is difficult to go to a competitor and ask this. It’s also not especially practical to go and find some non-competing company in a different industry you don’t understand well. An entire industry has emerged to assist with this question.

We talked about the role of industry analysts in chapter 8. Benchmarking firms play a similar role, and in fact, some analyst firms provide benchmarking services.

There are a variety of ways benchmarking is conducted, but it is similar to assurance in that it often follows the 3-party model. Some stakeholder directs an accountable party to be benchmarked within some defined scope. For example, the number of staff required to managed a given quantity of servers (aka admin:server) has been a popular benchmark. (Note that with cloud, virtualization, and containers, the usefulness of this metric is increasingly in question).

An independent authority is retained. The benchmarker collects, or has collected, information on similar operations; for example, they may have collected data from 50 organizations of similar size on admin:server ratios. This data is aggregated and/or anonymized so that competitive concerns are reduced. Wells Fargo will not be told “JP Morgan Chase has an overall ratio of 1:300;” they will be told, “The average for financial services is 1:250.”

In terms of formal assurance principles, the benchmark data becomes the assessment criteria. A single engagement might consider dozens of different metrics, and where simple quantitative ratios do not apply, the benchmarker may have a continuously maintained library of case studies for more qualitative analysis. This starts to shade into the kind of work also performed by industry analysts. As the work becomes more qualitative, it also becomes more advisory and less about “assurance” per se.

10.5.2. Audit

The Committee, therefore, recommends that all listed companies should establish an audit committee.

Agile or not, a team ultimately has to meet legal and essential organizational needs and audits help to ensure this.

Disciplined Agile Delivery

If you look up “audit” online or in a dictionary, you will see it mainly defined in terms of finance: an audit is a formal examination of an organization’s finances (sometimes termed “books”). Auditors look for fraud and error so that investors (like our shop owner) have confidence that accountable parties (e.g.,the shop manager) are conducting business honestly and accurately.

Audit is critically important to the functioning of the modern economy because there are great incentives for theft and fraud, and owners (in the form of shareholders) are remote from the business operations.

But what does all this have to do with information technology and digital transformation?

Digital organizations, of course, have budgets and must account for how they spend money. Since financial accounting and its associated audit practices are a well established practice, we won’t discuss it here. (We discussed IT financial management and service accounting in Chapter 8).

Money represents a form of information, that of value. Money once was stored as a precious metal. When carrying large amounts of precious metal became impossible, it was stored in banks and managed through paper record keeping. Paper record keeping migrated onto computing machines, which now represent the value once associated with gold and silver. Bank deposits (our digital users bank account balance from Chapter 1) are now no more than a computer record -— digital bits in memory -— made meaningful by tradition and law, and secured through multiple layers of protection and assurance (see Money, from physical to virtual [6]).

Because of the increasing importance of computers to financial fundamentals, auditors became increasingly interested in information technology. Clearly, these new electronic computers could be used to commit fraud in new and powerful ways. Auditors had to start asking, “How do you know the data in the computer is correct?” This led to the formation in 1967 of the Electonic Data Processing Auditors Association (EDPAA), which eventually became ISACA (developer of CObIT).

It also became clear that computers and their associated operation were a notable source of cost and risk for the organization, even if they were not directly used for financial accounting. This has led to the direct auditing of information technology practices and processes, as part of the broader assurance ecosystem we are discussing in this chapter section.

A wide variety of IT practices and processes may be audited. Auditors may take a general interest in whether the IT organization is “documenting what it does and doing what it documents” and therefore this author has seen nearly every IT process audited.

IT auditors may audit projects, checking that the expected project methodology is being followed. They may audit IT performance reporting, such as claims of meeting Service Level Agreements. And they audit the organization’s security approach — both its definition of security policies and controls, as well as their effectiveness.

External versus internal audit

There are two major kinds of auditors of interest to us:

-

External auditors

-

Internal auditors

Here is a definition of external auditor:

An external auditor is chartered by a regulatory authority to visit an enterprise or entity and to review and independently report the results of that review. [187 p. 319].

Many accounting firms offer external audit services, and the largest accounting firms (such as PriceWaterhouse Coopers and Ernst & Young) provide audit services to the largest organizations (corporations, non-profits, and governmental entities). External auditors are usually certified public accountants, licensed by their state, and following industry standards (e.g.,from the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants).

By contrast, internal auditing is housed internally to the organization, as defined by the Institute of Internal Auditors:

Internal auditing is an independent appraisal function established within an organization to examine and evaluate its activities as a service to the organization [187], p. 320.

Internal audit is considered a distinct but complementary function to external audit. [69], 4_39. The internal audit function usually reports to the audit committee. As with assurance in general, independence is critical — auditors must have organizational distance from those they are auditing, and must not be restricted in any way that could limit the effectiveness of their findings.

Audit practices

As with other forms of assurance, audit follows the three-party model. There is a stakeholder, an accountable party, and an independent practitioner.

The typical internal audit lifecycle consists of (derived from [138]):

-

Planning/scoping

-

Performing

-

Communicating

In the scoping phase, the parties are identified (e.g.,the board audit committee, the accountable and responsible parties, the auditors, and other stakeholders). The scope of the audit is very specifically established, including objectives, controls, and enablers (e.g.,processes) to be tested. Appropriate frameworks may be utilized as a basis for the audit, and/or the organization’s own process documentation.

The audit is then performed. A variety of techniques may be used by the auditors:

-

Performance of processes or their steps

-

Inspection of previous process cycles and their evidence (e.g.,documents, recorded transactions, reports, logs, etc.)

-

Interviews with staff

-

Physical inspection or walkthroughs of facilities

-

Direct inspection of system configurations and validation against expected guidelines

-

Attempting what should be prevented (e.g.,trying to access a secured system or view data over the authorization level)